Extraction

By John L. Scheels

After oral examination and dental prophylaxis, tooth extraction is the most common procedure performed in veterinary dentistry, including zoo dentistry. In captive exotic animal institutions this is quite appropriate because of the general anesthesia risks and the limitations of follow up. In fact, in zoo dentistry, dental prophylaxis is usually not considered very significant. It is often considered a secondary concern in most cases, with exceptions.

Therefore, a dentist trained to treat humans only, intending to serve as a zoo dental consultant, should be very experienced in tooth extraction. Proper tooth extraction technique should use sound surgical principles. Proper technique minimizes post operative discomfort and optimizes rapid healing of alveolar bone and associated soft tissues. Thorough knowledge of the oral anatomy is always fundamental to tooth extraction and other oral surgical procedures.

A dentist trained on humans, intending to serve as a zoo dental consultant should be very experienced in tooth extraction. This section uses the domestic dog as a basic example of how knowledge of a species anatomy is essential to perform basic oral surgery well. Various exotic species will also used to illustrate the wide range encountered in zoo dentistry.

The wide range of anatomy and dimensions encountered in zoo dentistry requires thorough preoperative preparation. This includes tooth anatomy; tooth dimensions; proximity and relationship to adjacent teeth and surrounding anatomy including nervous and vascular tissues. A key point here is that the tooth root anatomy and dimensions are most important. Oral cavity access varies from the very wide opening mouths of felidae to the limited openings of rodentia.

All of these factors must be considered when preparing to perform extractions. They dictate technique and instrumentation. And again, the limitations of anesthesia and follow up will influence considerations of extraction site management such as alveolus packing and closure.

Indications For Extraction

Indications for extracting teeth include periodontal disease, fractured teeth, tooth pulp disease, malposition, overcrowding, and teeth located within a fracture line. Less commonly encountered indications include the presence of a tooth within a bone cyst and impacted teeth that disrupt normal dentition.

Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory, degenerative disease of the gingiva and bone. Periodontal disease can be considered a chronic infection and is the most common cause of tooth loss in the dog (as it is in almost every species, including humans). Only in its late stages does it become painful, caused by the mobility of the diseased teeth. Subsequent alveolar bone resorption and root exposure, pain, and acute infection finally necessitates extraction of the affected teeth.

A tooth fractured beyond repair (or beyond the owner's financial commitment to preserve the tooth) should be extracted. However, a coronal fracture without pulpal exposure may be conservatively treated by recontouring sharp edges to avoid irritation to the soft tissues. Fresh pulpal exposures may be treated by calcium hydroxide pulp capping, partial pulpectomy, or complete endodontic therapy and conservative restoration of the crown.

Generally, a tooth within a fracture line should be extracted. The periodontal ligament along the fracture line is disrupted by the fracture. Cementum covering the root that is exposed by a fracture of the alveolar bone rapidly becomes nonviable and can retard osteogenesis. Ankylosis can occur between the cementum and alveolar bone with destruction of the periodontal ligament and loss of its normal shock absorbing function. Subsequent forces placed on the tooth during chewing are transmitted directly to the underlying bone. Eventually, the constant trauma may cause the tooth to fracture, become loose, or disrupt the alveolar bone, necessitating its extraction. Despite an interruption in bone integrity with disruption of the periodontal ligament, the vascular and nerve supply to the tooth may remain intact. However, if the vascular and nervous supply is destroyed, pulpal necrosis will occur, predisposing the tooth to infection and the alveolar fracture to nonunion. If the involved tooth aids in preventing displacement of the fracture, or assists in the stabilization of the fracture, it should be retained until the fracture has healed. Thorough periodic radiographic evaluation of the fracture and involved teeth will determine if and when they must be extracted.

Pulpal infection can have several causes, including direct damage to the pulp, trauma, or caries (decay). Low-grade chronic inflammation can cause irreversible pulpal necrosis leading to abscess formation. Endodontic therapy can preserve abscessed teeth if associated alveolar bone involvement is not extensive. As a general rule, especially in zoo practice, endodontic therapy should considered only for critical functionally and structurally important teeth such as the canine, carnassials and very easily accessible anterior teeth that may be restored conservatively. Endodontic therapy requires at least one general anesthetic procedure and specialized training and equipment. If endodontic treatment is not available immediately, or by referral, the tooth must be extracted.

Malposed or crooked teeth frequently caused by retained primary teeth or overcrowding can result in improper occlusion, food impaction, periodontal disease, trauma to adjacent teeth and tissues, or trauma to teeth and tissues in the opposing arch. Malposed teeth should be removed if they are causing a pathological condition and cannot be modified or conservatively orthodontically repositioned.

In its simplest description, tooth extraction involves the removal of the tooth root from the bony socket, properly termed the alveolus. Removal of a tooth with a degenerated alveolus caused by periodontal disease may be deceptively easy; however, when a tooth or root is held firmly, removal can be challenging and difficult. From my experience animals teeth are held more tightly than human teeth within the alveolar bone. In all mammals, teeth are held in place by the periodontal ligament, which is a complex of connective tissue fibers attaching the cementum that covers the root to the alveolar bone. Although providing a firm attachment, the periodontal ligament normally permits slight tooth mobility, providing a shock-absorbing function. Knowledge of specific tooth root morphological characteristics, approximate dimensions, and three-dimensional relationship to adjacent structures is mandatory. Preoperative radiographs must be used to identify and document lesions involving the tooth and its root(s). Radiographs are also essential in detecting unusual or abnormal anatomic and morphological variations of the tooth and its root(s). However, because radiographs may not always be available, a thorough knowledge of the normal subgingival features of the tooth is very important.

Dog Tooth Root Morphology

This section will use the domestic dog as a basic example to show how the knowledge of a species anatomy is necessary to perform basic oral surgery well. Various exotic species will also be used to illustrate the wide range encountered in zoo practice. A dentist trained on humans must learn a number of significant differences in various mammal groups' skeletal anatomy. For example, carnivores have cartilaginous mandibular midline symphysis. The symphisis in many herbivores is also cartilaginous and is much more flexible than in carnivores.

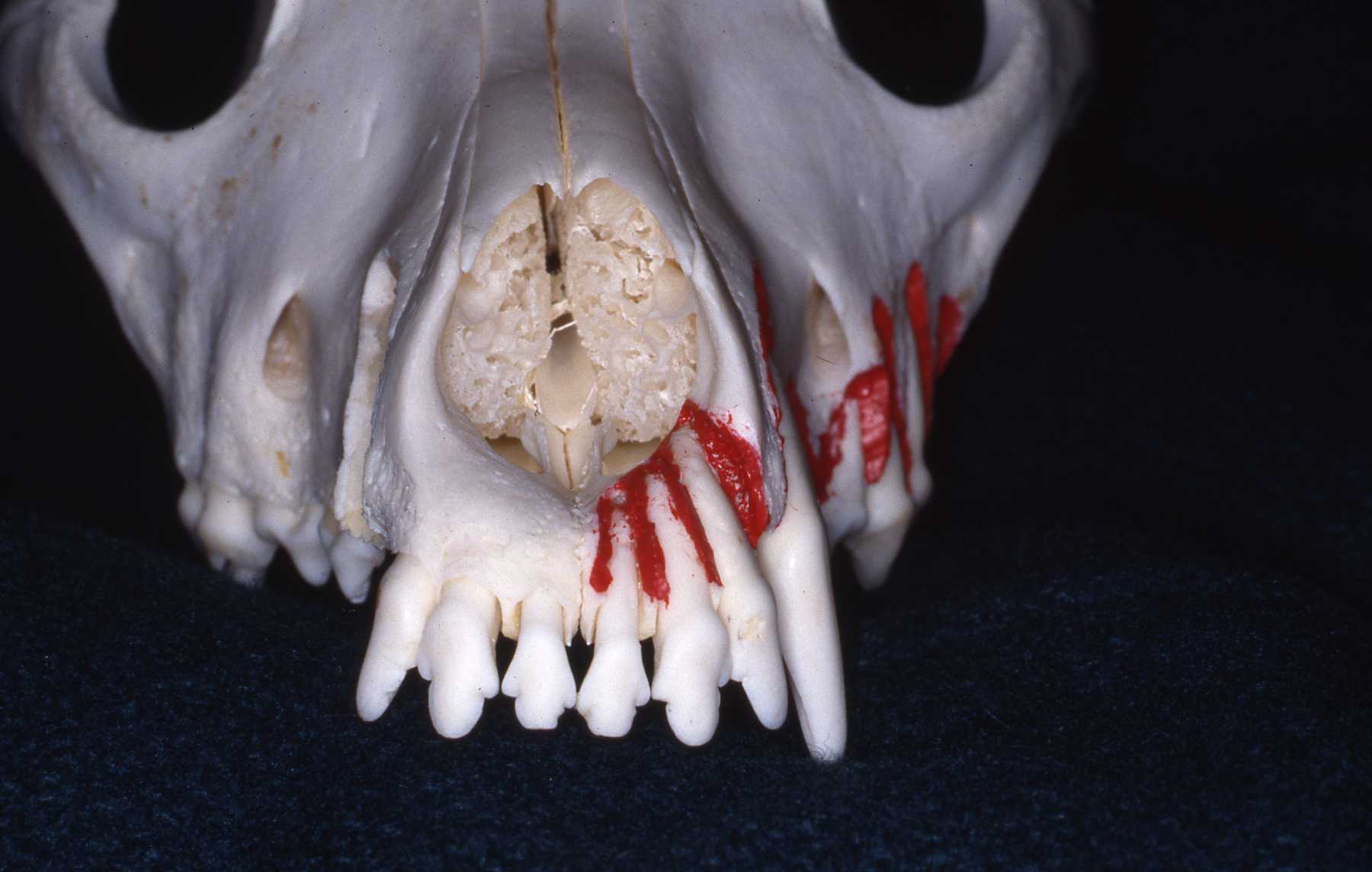

In the dog, the maxillary incisors vary in their crown height to root length ratios. The shortest rooted teeth are the first or central incisors. whereas, the third or lateral incisors have the largest roots. The roots have an oblong cross section. being quite flat on their lateral surfaces. The roots curve caudally with their apices reaching to within a few millimeters of the nasal cavity (Fig 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1

The maxillary canine root is similarly shaped to the incisors, only being much larger in dimension. The medial side of the apical halfof the canine root lies within 2 mm of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. During extraction, a medially or palatally directed force easily can fracture the delicate bone separating the roots of these teeth from the nasal cavity and tear the nasal epithelial lining. An oronasal fistula can occur if the nasal epithelium heals to the oral mucosa. Careful controlled technique can prevent this complication from occurring. Iatrogenic oronasal fistulae frequently require surgical correction.

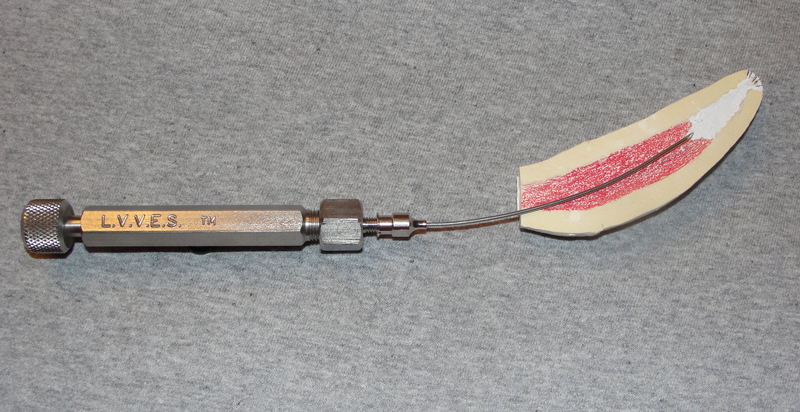

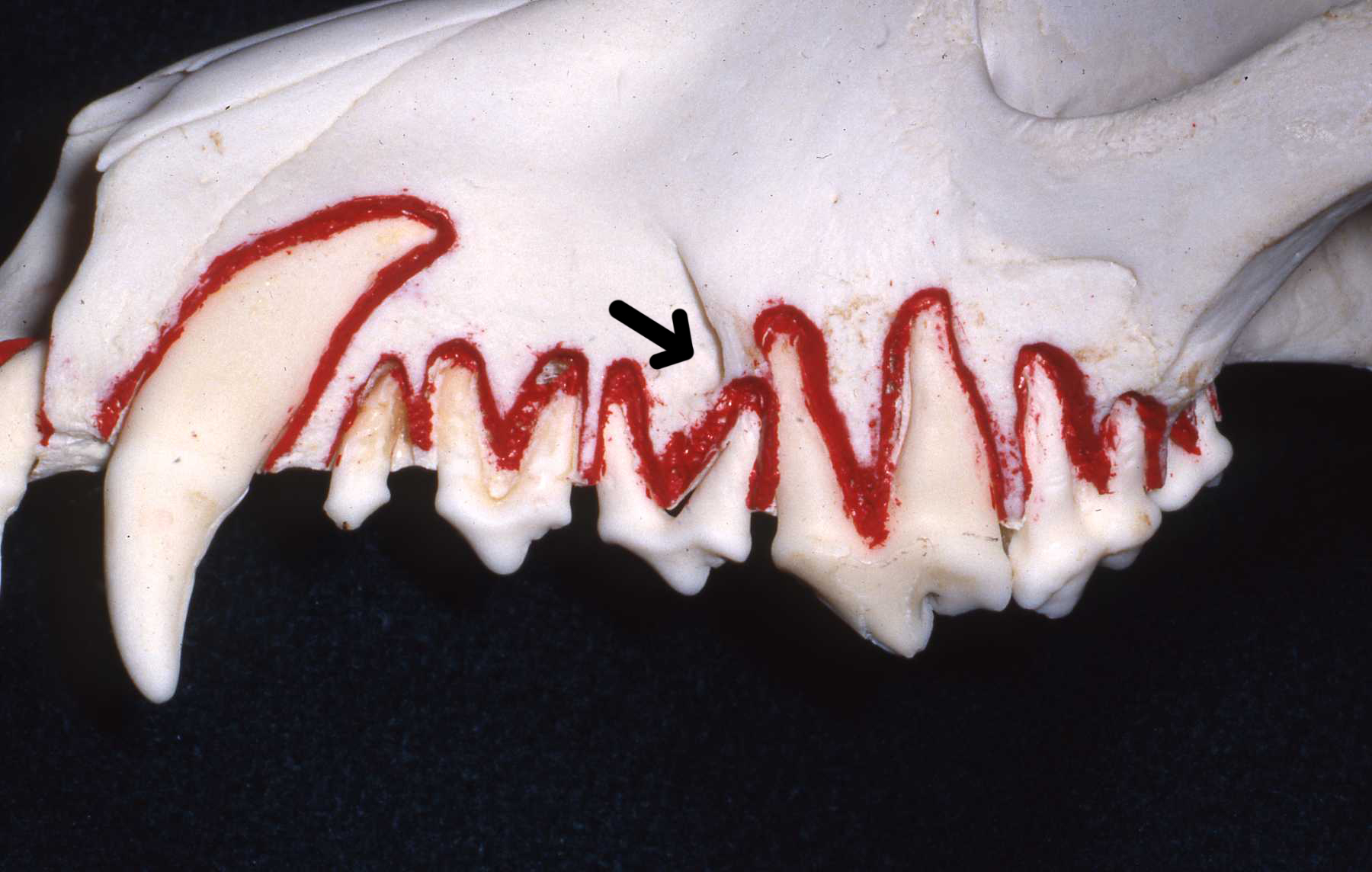

Extraction forceps can be used on the maxillary incisors with a limited amount of axial rotation, resisted by the flattened root sides. Palatal and labial tipping is possible, however, caution should be exercised during this manipulation to prevent fracture into the nasal cavity. The canine tooth deserves special attention because of the formidable anchorage of its massive root (Fig 2). The technique for extraction of canine teeth will be discussed later.

Figure 2

Figure 2

The maxillary first premolar has a single straight conical root permitting easy rotation with extraction forceps. However, the second and third premolars each have two roots lying in a rostralcaudal (mesial-distal) position that resist rotation with extraction forceps. The conical roots diverge from one another along their lengths resisting removal. Repeatedly tipping in the labial and lingual directions can be effective. Sectioning the tooth into two single-rooted units permits much easier removal, and reduces the likelihood of breaking the root within the alveolus. The distal or caudal root apex of the third premolar lies in close proximity to the infraorbital foramen, and the foramen must be located and avoided when using the surgical openview technique to extract this tooth (Fig 2).

Figure 3

Figure 3

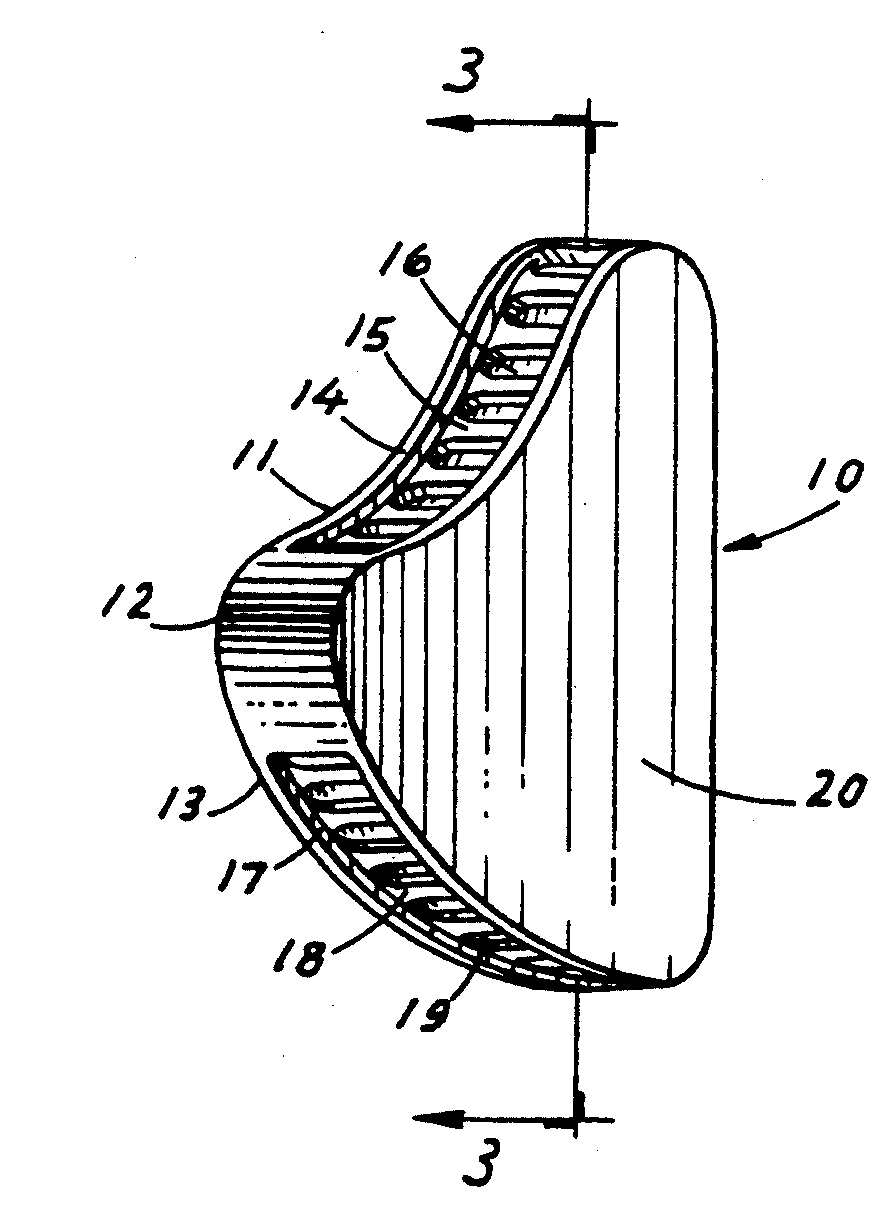

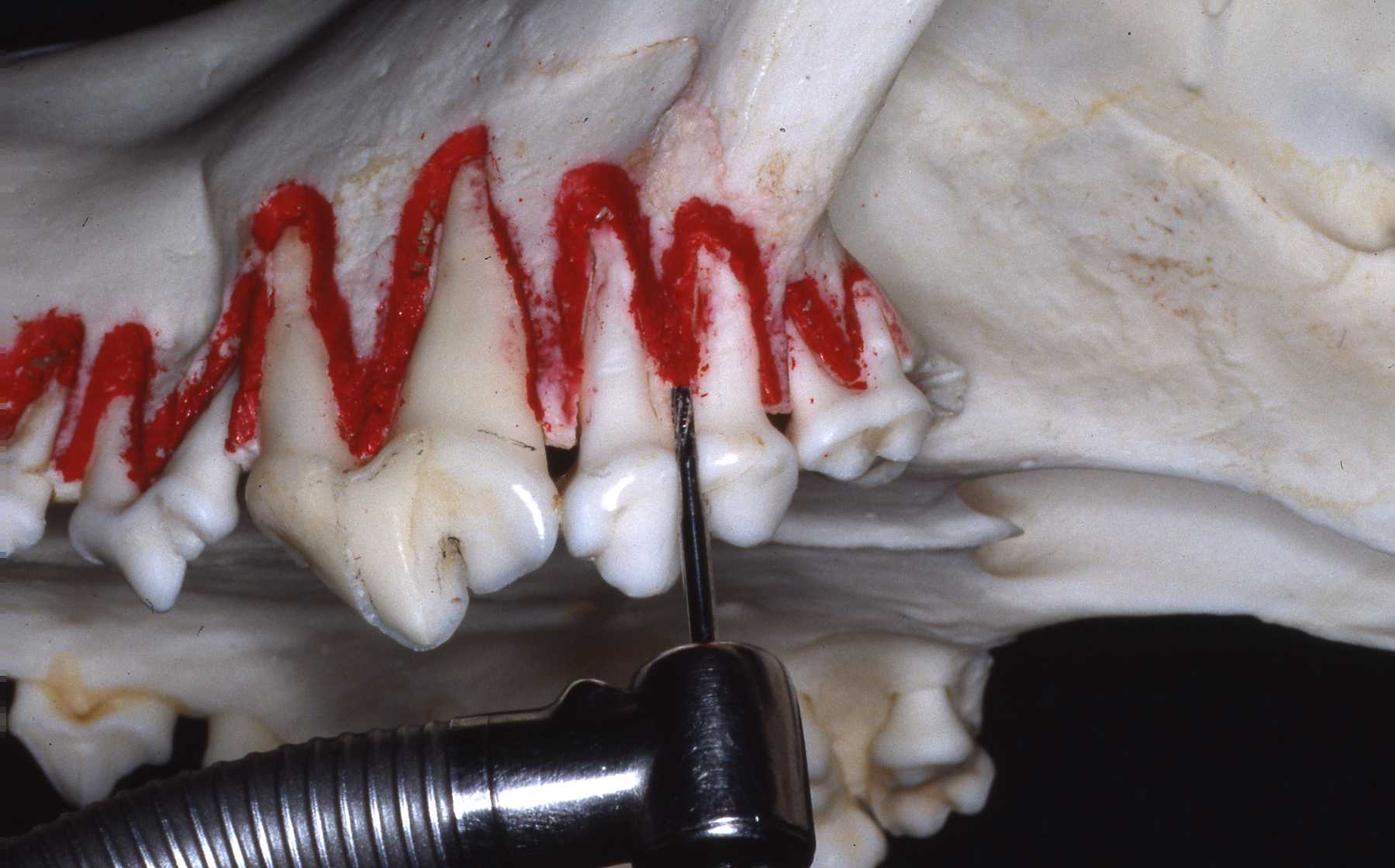

The fourth maxillary premolar (carnassial tooth) has three roots. Two large conical roots lie in the same rostral-caudal plane as the other premolar roots, with a third smaller palatal root lying medial to the rostral root (Figs 2 and 3). The rostral root is conical whereas the caudal or distal root is more massive with flattened medial and lateral surfaces. Sectioning this tooth into either two or three units facilitates removal.

The first and second maxillary molars each have three roots in a diverging tripod configuration; their palatal or medial roots are similar in size to the lateral roots and located midway rostral-caudal to the tooth crown (Figs 2 and 3). Sectioning these molars into three single-rooted units also greatly facilitates their removal (Fig 4).

Figure 4

Figure 4

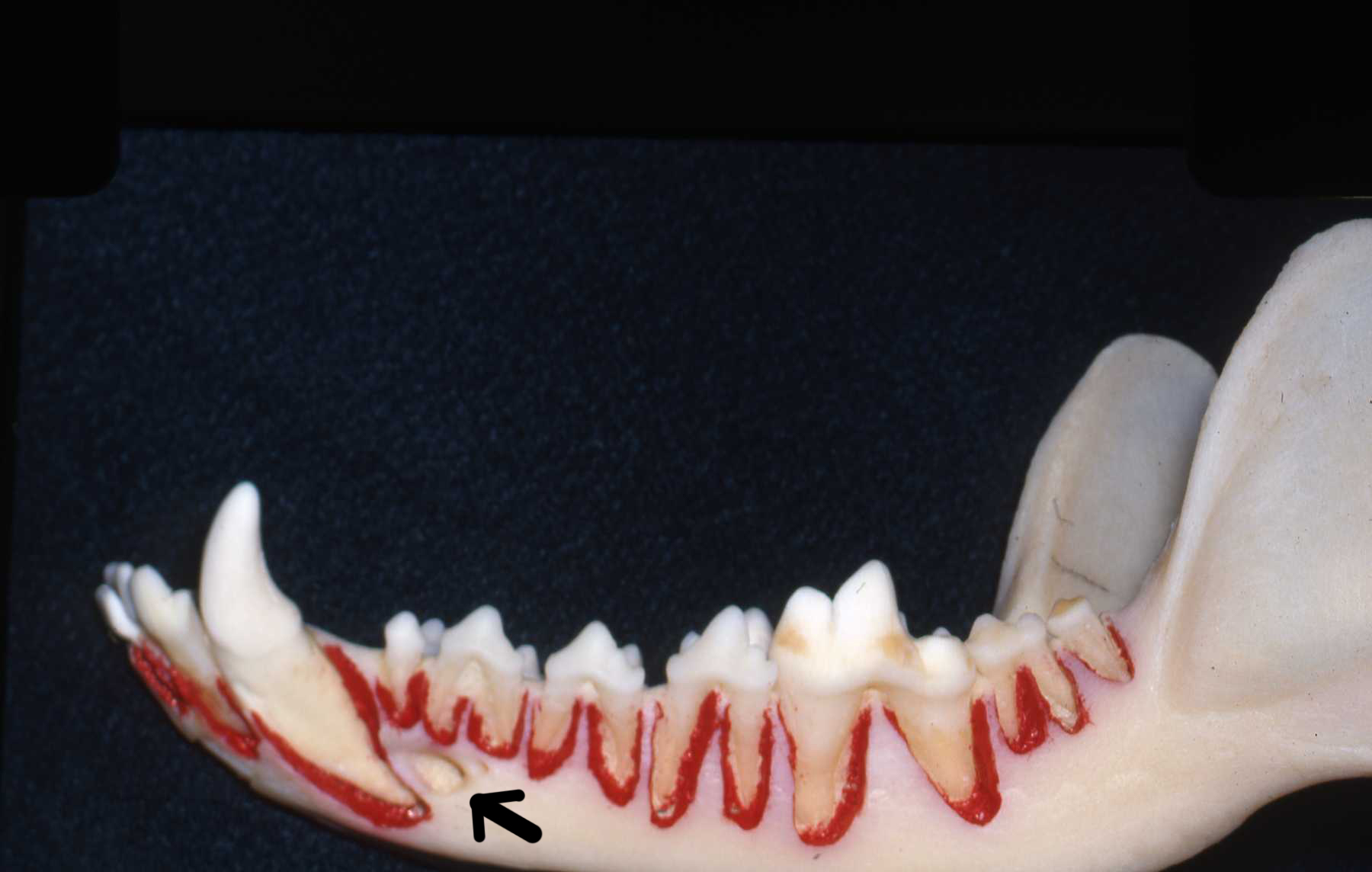

The mandibular incisors have long slender roots that are relatively straight with flattened sides yet are more cylindrical than their maxillary counterparts. The third incisor is much larger than the first and second incisors and has a long root. The mandibular canine teeth, like the maxillary canine teeth, are very large. The massive root curves caudally with its apex extending beneath the rostral root apex of the second premolar, and lies in close proximity to the mental foramina. The vascular and nervous structures exiting the foramina and the large labial frenulum caudal to the canine tooth must be avoided (Fig 5).

Figure 5

Figure 5

In the mandible, the bone surrounding the lateral aspect of the canine, premolar, and molar roots is approximately twice as thick as that of the maxilla. This thicker bony support presents considerable resistance to tooth extraction. The use of heavy force can cause injury to the mandibular symphysis and temporomandibularjoints. Excessive force exerted in the presence of severe periodontal disease can cause fracture of the compromised bone. Firm support of the mandible, proper technique, and controlled force are necessary to minimize iatrogenic trauma during dental extractions.

Figure 6

Figure 6

The mandibular first premolar and third molar are relatively easy to remove because they have single straight conical roots and can be axially rotated using extraction forceps. The second, third, and fourth premolars. and first and second molars all have two conical diverging roots lying in rostral-caudal alignment, with massive bony support strongly resisting rotation using extraction forceps. Tipping in labial and lingual directions can be effective, but initially progresses very slowly. Be patient! Premature or overly aggressive us of the forceps can result in fracture of the root within the alveolus. Again, sectioning of these teeth greatly facilitates their removal. particularly for the massive rooted first mandibular molar (Fig 6).

This page:

Introduction, Indications, Morphology

Page 2: Techniques

Page 3: Postoperative Care, Extraction of Feline Teeth, Summary