Page 2 - Extraction

Extraction Techniques

By John L. Scheels and Paul E. Howard

Before beginning the operative procedure, several important considerations concerning animal patient and operator comfort and safety should be addressed. The anesthetized animal should be placed in a comfortable position that allows for easy access to the side of the oral cavity being operated on. The endotracheal tube should be secured away from the operative area, and the jaws should be securely propped open without unnecessary strain on the temporomandibular joints. Various mouth props such as a needle caps, tape rolls, the WEDGE, commercial human props for primates, wooden blocks can be used. Well designed retractors are available for rabbit size rodents. Equine systems are available for large hoofstock. Many situations will still require an assistant to support the patients' head and aid in retraction. The operator must be in a comfortable position that permits an efficient, controlled procedure. Good lighting is essential. Plan ahead for treatment in enclosures. We use various spot lights, various wand lights and head lamps. In the zoo setting these fundamental conditions may not be easy to achieve. It is always preferable to treat patients in a clinical or hospital setting but that is often not possible. See the photos on this website which illustrate treating various zoo animals in their enclosures. Thorough logistic planning prior to anesthesia is especially imperative in the enclosure settings for a successful procedure.

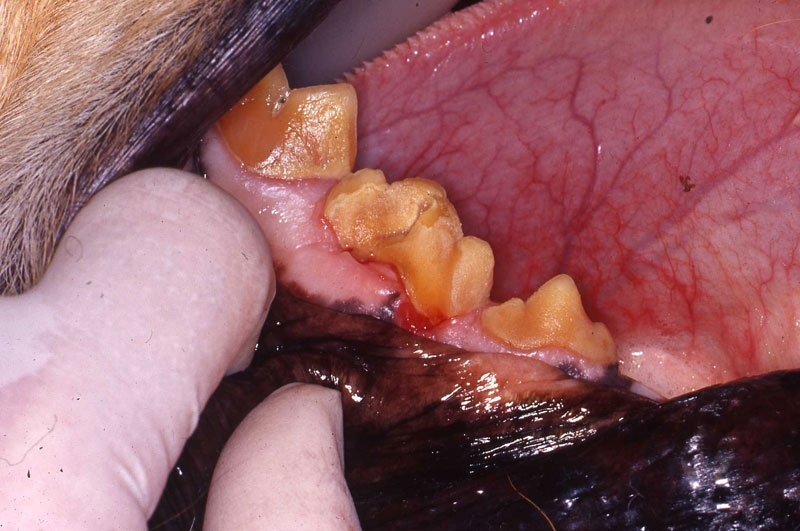

Cleanse the area of the procedure by rinsing away food particles and using an antiseptic rinse of choice. The initial operative step of tooth extraction is to incise the entire circumference of the gingival attachment at the base of the gingival sulcus. Either a small scalpel blade or a sharp bone curette works well.

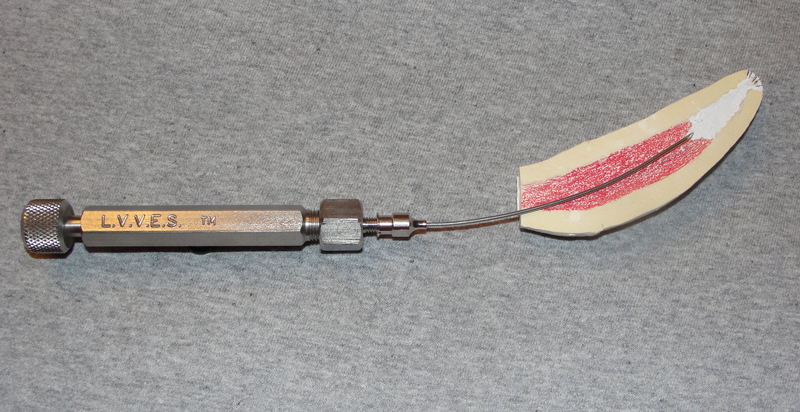

Luxator Technique

I have utilized the luxator technique since it was first explained to me by my colleague, Dr. Peter Kertesz (London Zoo). The orginal luxators from Scandanavia and Coupland chisels were designed for human dentistry. Numerous new variations are now available from human and veterinary manufacturers. Narrow osteotomes are also useful to achieve minimally traumatic tooth extraction. For very small teeth I regularly use appropriate size needles. This was suggested to me by observant zoo technicians Margaret Michaels and Joan Maurer when they were watching me struggle removing fruit bat canine roots.

The luxator, sharp curved edge or Coupland chisel sharp flat edge is forced into the periodontal ligament space between the root and alveolar bone in the long axis of the tooth. The periodontal ligament is severed with a controlled rotating motion to wedge the root loose. The appropriate size is chosen, changing to larger sizes as the loosening progresses until the root is free. The instrument handle should be held in the palm of the hand, and the index finger is used to direct the instrument and protect against dislodging the tip. Digital palpation of the alveolar bone with the operator's second hand can assess the progress of the extraction. Curved roots, such as those of the canine teeth, are not amenable to this technique. Caudal teeth may not be accessible, which limits the use of this technique as well. However, human size posterior luxators are available. Blunt-ended elevators cannot be used in this manner. They will not fit within the periodontal ligament space without causing excessive trauma.

Very narrow, curved luxators are now available with convex surface on the outside and inside of the curved blades. I use these Cislak luxators. Note that like all luxators they must be sharpened when dulled. I use size no. 8 round burs and narrow stone burs on a handpiece to maintain them.

Elevator Technique

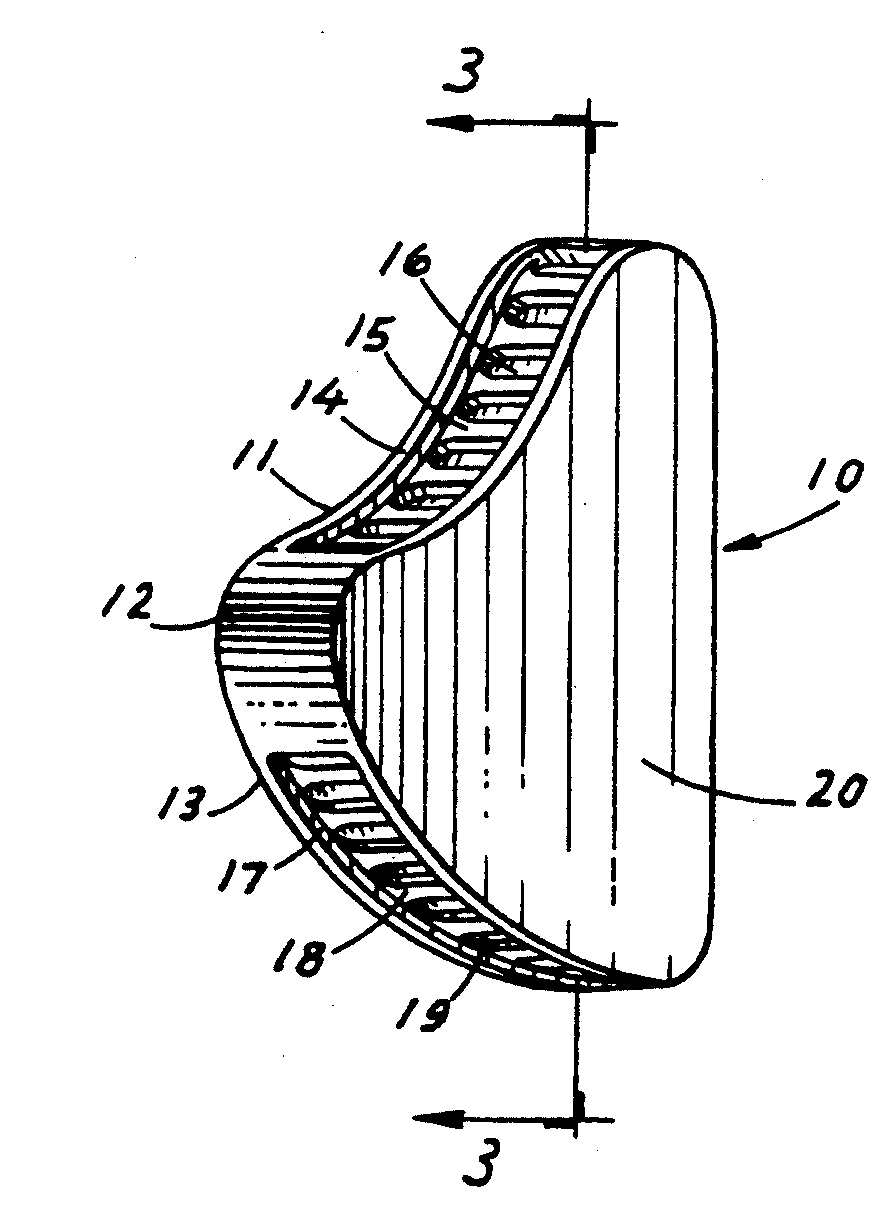

The straight dental elevator resembles a screwdriver. Its working end consists of a blade with a concave surface and an opposing convex surface. The tip may be sharp or blunt.

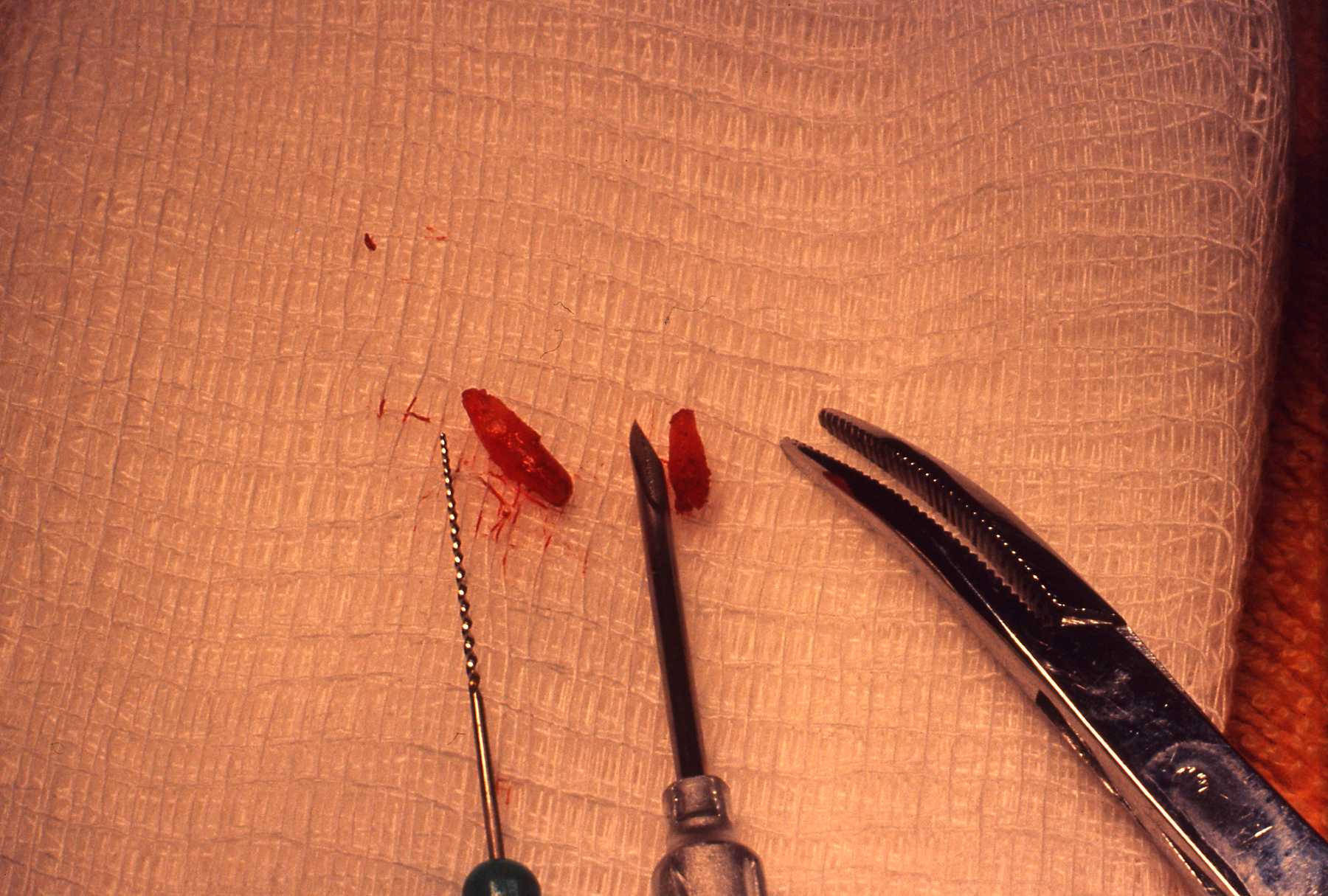

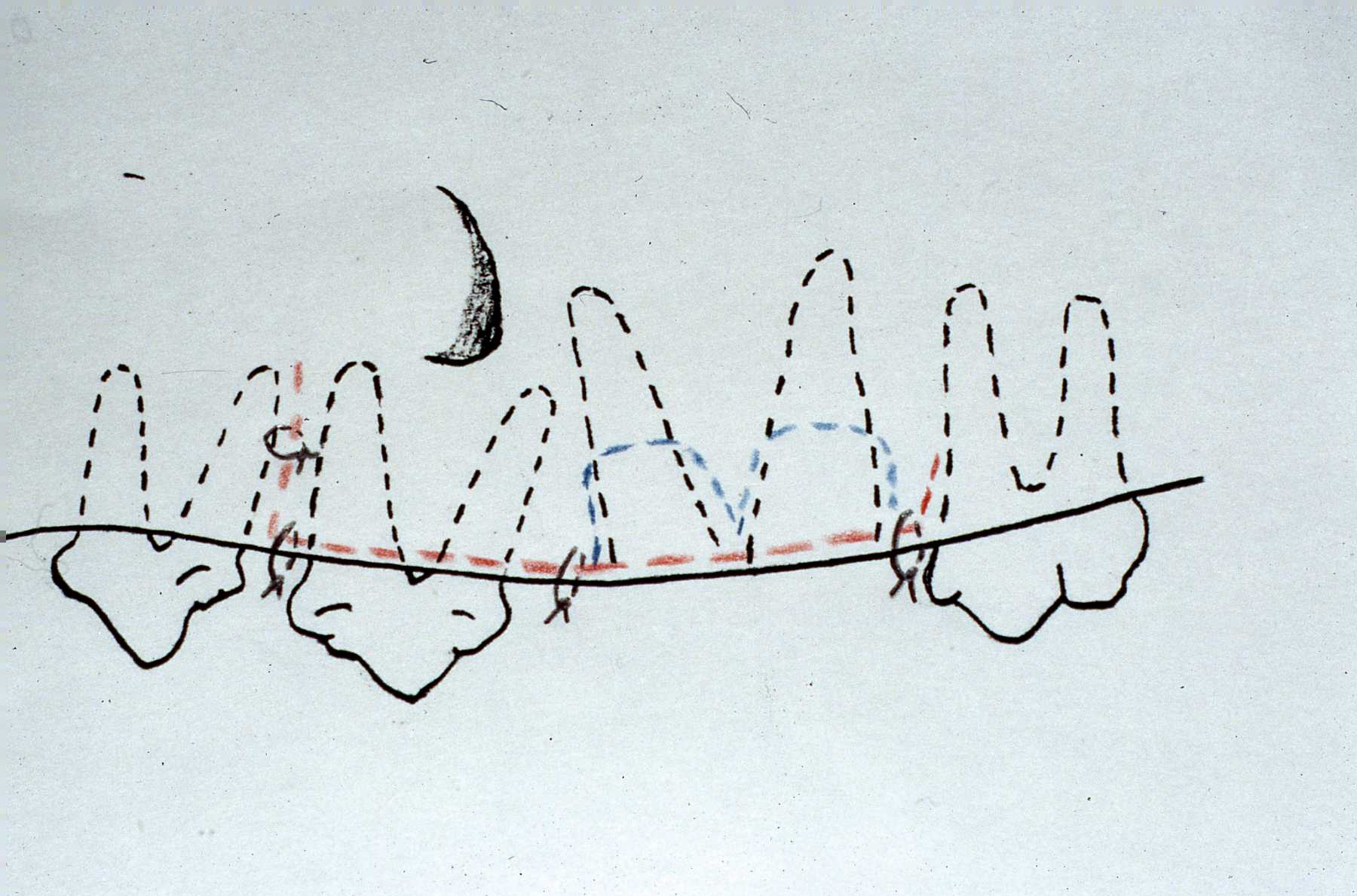

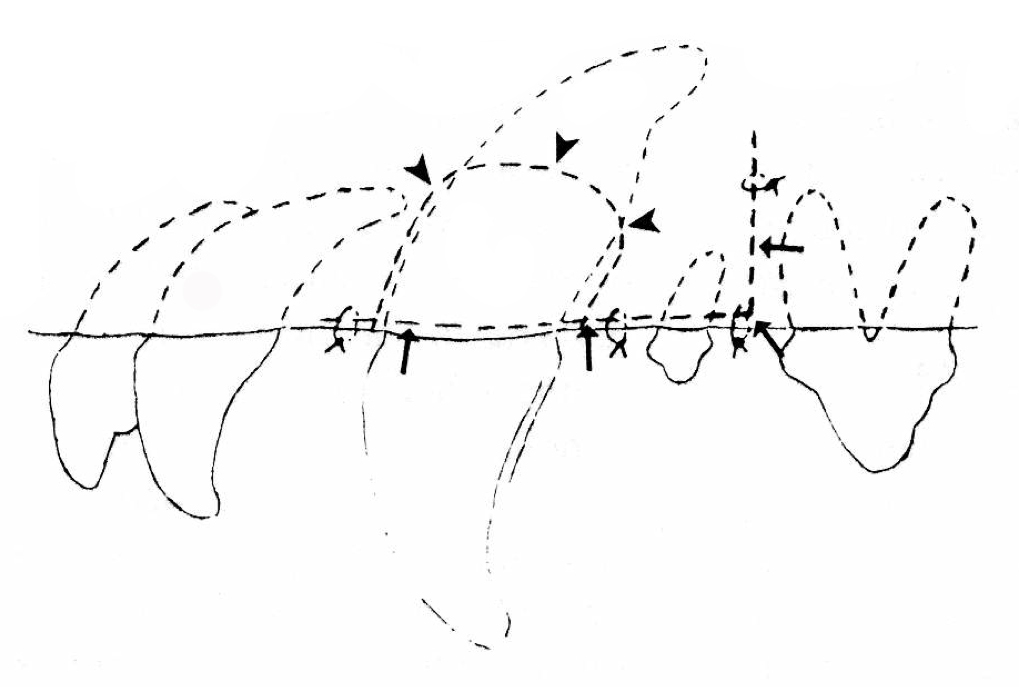

Figure 7

Figure 7

Straight elevators are used to lever between adjacent teeth by rotating on its long axis, using one tooth or tooth segment as a fulcrum wedging them apart creating the elevation of the desired tooth or segment. (Figure 7) The elevator is rotated on its long axis like a screwdriver with the concave surface edge engaging and elevating while the convex surface rests against the fulcrum segment. All segments should be thoroughly loosened before any are lifted free with a forceps. If an elevator is used in this manner, using an adjacent tooth that is not to be extracted, as a fulcrum, extreme caution must be exercised. It should only be a larger, stable tooth, and may be further supported by the operator's second hand.

Elevators with various long and curved or triangular-shaped ends are used to dislodge root pieces in either the conventional or surgical techniques. Such "root" elevators with serrated edges are superior in engaging retained fragments.

Occasionally, soft tissues can be lacerated or bone can be crushed by aggressive elevator use. Lacerated tissue should be contoured and possibly sutured to create as smooth a surface as possible. Irregular, sharp, or crushed bone should be contoured with ronguers, a bone rasp, or a handpiece with a dental bur. Soft tissues can then be sutured over the defect in a tension-free manner.

Extraction Technique Tip

When extracting posterior teeth that have tight interproximal contact, I cut the tooth contacts away to create a space ("kerf") between the adjacent teeth. This permits interproximal access for luxators and elevators. This creates mesiaI/distal, anterior/posterior or rostral/caudal (whatever your nomenclature inclination) space in which to move the tooth. This simple brief step significantly facilitates tooth luxation because then you can move the tooth in four lateral directions instead of just two.

I also do this in my human practice on premolar and molar extractions. Use a 557 or 556 crosscut fissure bur. If I inadvertently scratch the contact area of an adjacent tooth I polish it with an ultrafine diamond bur. It happens.

Forceps Technique

Dental forceps (extractors) are used by grasping the tooth or root as far apically as possible with the beak of the forcep aligned with the long axis of the tooth. The tooth is gripped tightly enough so that no slipping occurs and the forceps are repeatedly tipped or rotated until the periodontal ligament is broken down. Heavy brute force is to be avoided. It can cause fracture of the tooth and complicate the procedure. A very effective technique when either tipping or rotating, is to exert the force in one direction and then the opposite direction, alternating with rotation of the tooth on its long axis. When either tipping or rotating, the operator should maintain pressure for several seconds at one extreme position, then reverse direction and maintain pressure in the opposite extreme position. Initially, these pressures may be strongly resisted with little or no apparent progress evident, but as this procedure is repeated, the tooth eventually loosens. Rapid tipping motions are not as effective. Traction on the tooth with extraction forceps should be avoided. Once the periodontal ligament breaks down, the tooth can be gently lifted free of the dental alveolus.

Using extraction forceps with controlled forces can be an effective technique for large curved and rooted teeth if the operator has sufficient patience to get through the initial resistance to manipulation. In the canid dentition for example, caution must be exercised no to force the root apex of the maxillary third incisor or canine into the nasal cavity. Carefully choose the forceps that most accurately grasps the tooth with the maximum amount of surface area. The operator should avoid grasping the tooth with only a narrow edge of contact between the tooth and forcep. Use of improperly sized forceps can lead to fracture of the tooth, increased surgical time, and operator frustration. Besides human pediatric and adult sized forceps, many manufacturers of veterinary specific instruments are available. The author has purchased surplus forceps from various sources and modified the beaks to more effective shapes. The author has also done this with hemostats used as forceps for small diameter teeth.

All multi-rooted teeth are more easily and less traumatically extracted by sectioning into singlerooted units. The kerf made by sectioning permits elevator use as described earlier. The single-rooted units can then be rotated on their long axis using forceps. Sectioning is most readily performed with a high-speed air-driven dental handpiece and bur. Either the cylindrical straight or tapered, or round burs work effectively. A low-speed air-driven or electrical dental handpiece and bur also work well. Sectioning with wire saws or hacksaw blades are effective but much less efficient and great care should be taken to avoid damaging adjacent tissues. Water coolant should be used to prevent thermal injury to adjacent soft tissues and bone. Large diameter cutting discs should never be used in the confines of the oral cavity because of the risk of iatrogenic trauma.

Sectioning cuts should be planned to cut the tooth into equal units. The cuts are made in the long axis of the tooth. The cuts must go completely through to the furcation of the roots. This can be confirmed by gently using an elevator to confirm independent movement of the segments. The fourth maxillary premolar in the dog has a palatal root that may be sectioned at a 45° angle to the long axis of the tooth to reach the furcation. Some times this root is small and can be left intact and removed with the larger mesiobuccal (rostral) root.

Surgical Extraction or "Open-View" Technique

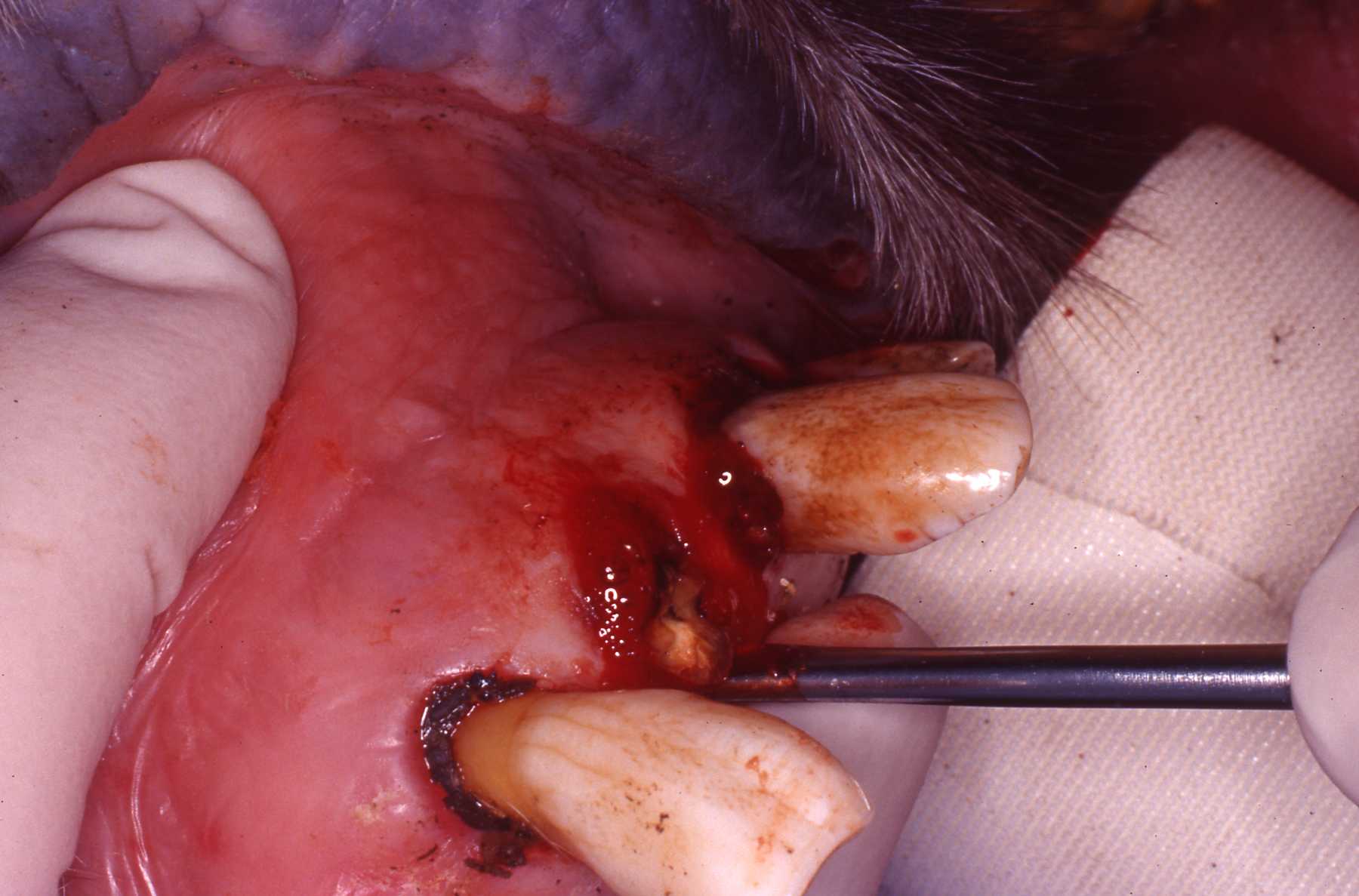

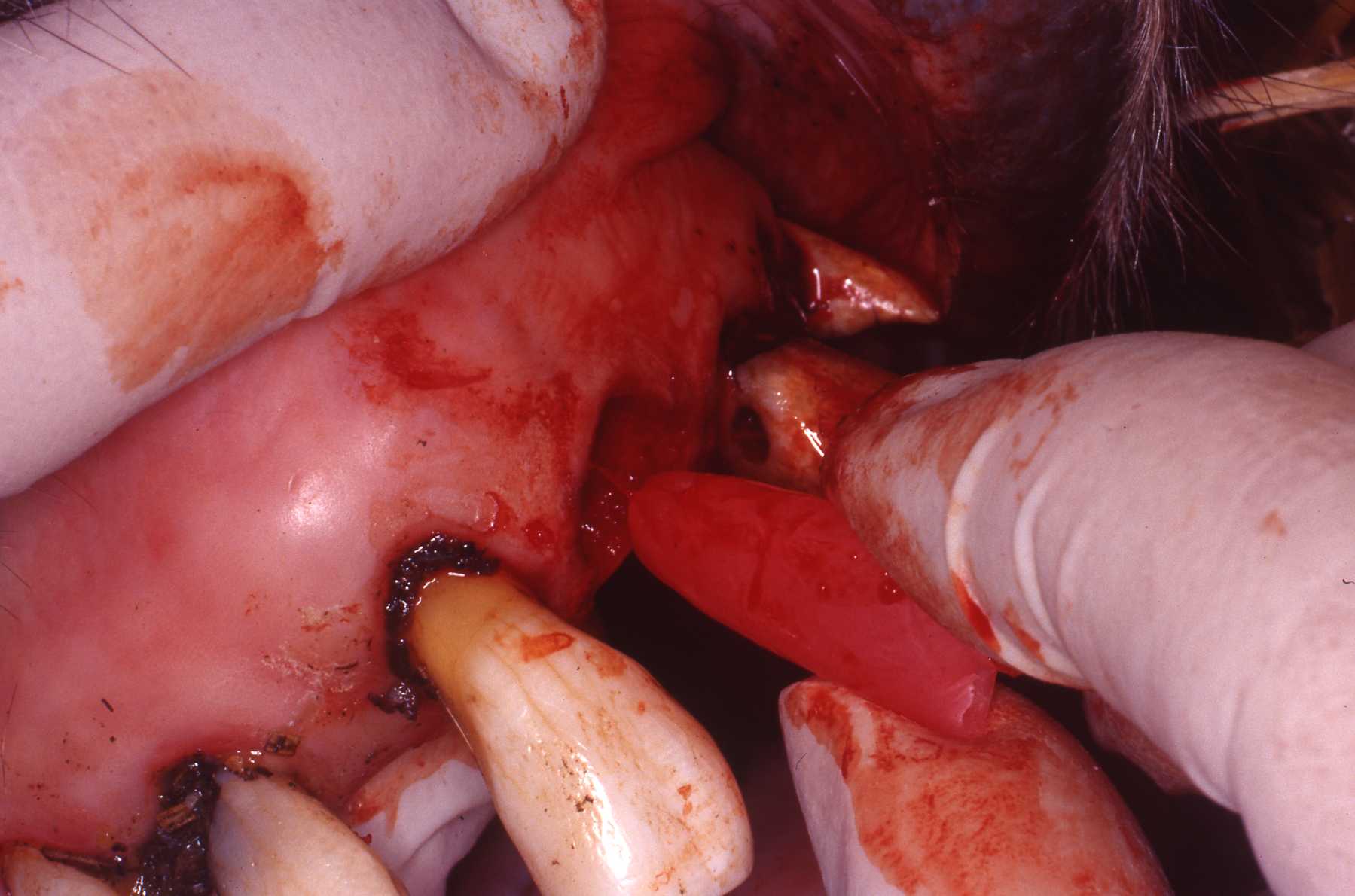

Surgical tooth extraction technique is preferred for the canine and carnassial teeth, or whenever a tooth crown has been fractured leaving only roots in the alveolus. However, over the last 20 years, the author has reduced the need for surgical flaps by well over 50% on retained root extractions by becoming experienced with the luxator technique. Surgical extractions may also be necessary for multi-rooted teeth when only one of the roots is diseased and the other root(s) remain unaffected (intact periodontal ligament). This technique involves the creation of a gingival flap and removal of bone overlying the roots of the tooth to be extracted. When performed properly, the surgical techniques is faster and less traumatic than prolonged use of dental elevators or forceps.

Properly planned flaps will facilitate the extraction, permit accurate closure of tissues, and optimize healing. Gingival flaps should be planned to avoid incision and subsequent suturing over voids created by the removal of bone and teeth, and to avoid stress on the suture line that may result in its dehiscence. The intraoral flap must be large enough to extend beyond an anticipated bony defect. Any releasing incisions should be made with local vascular and nervous supply and effective closure in mind. Basic flap design involves a horizontal incision across the interproximal gingival papilla between adjacent teeth on the crest of the alveolar ridge. Immediately adjacent to a tooth, an incision is made in the gingival sulcus. An oblique releasing incision in the gingiva is made at least one full tooth restral to the operative site. The corner of the flap should be placed between adjacent teeth if they are present, not beside the lateral surface of the tooth to be extracted (Fig 8).

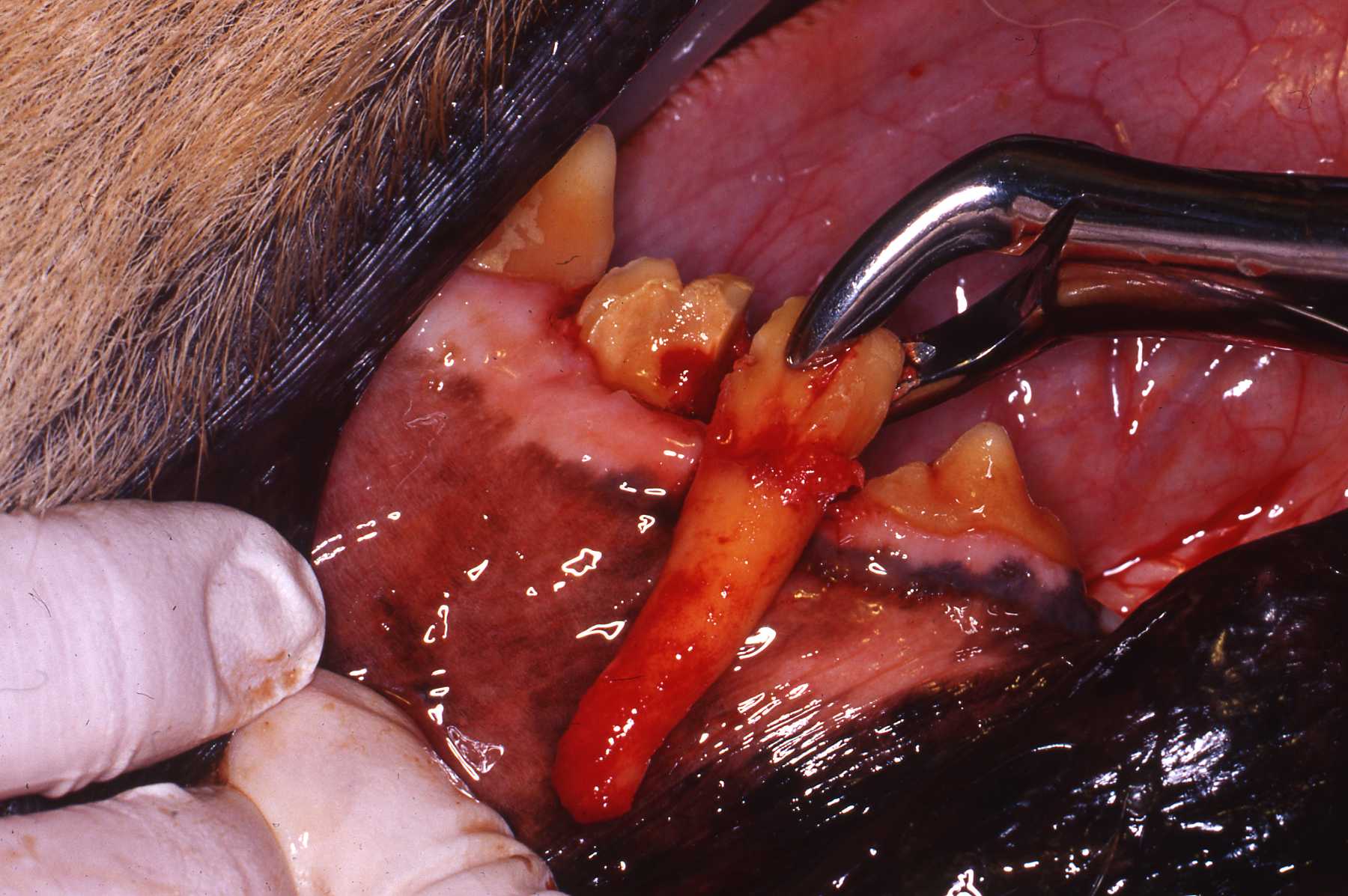

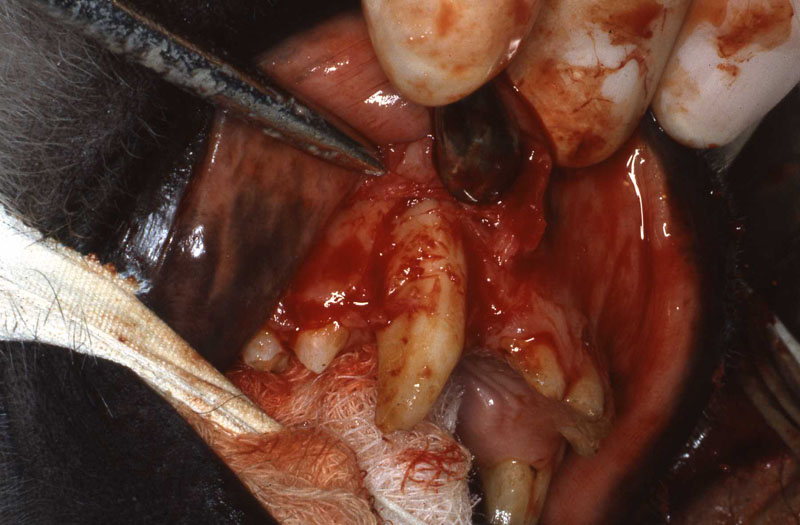

Figure 8

Figure 8

This permits effective closure of the extraction site wound. The flap generally is extended rostrally from the operative site to maximize accessibility. In the rostral region of the mouth, this is not necessary, but frena and muscles should be avoided to minimize edema, pain, and facilitate tension-free closure.

Specific neurovascular structures should be avoided when developing gingival flaps. The infraorbital foramen 'is located near the maxillary third and fourth premolar roots in the dog and near the maxillary canine, second, and third premolar roots in the cat. It must be identified and avoided because of the risk of injury to the infraorbital nerve and vessels. The mandibular frenulum between the canine tooth and premolars and the mental foramina should also be avoided. A conservative envelope flap design may be used lateral to the mandibular canine root. The incision should run along the crest of the alveolar ridge, through the gingival sulcus of the canine tooth on the labial side, and then extend from the third incisor to the first premolar. A groove can be cut into the alveolar bone with a dental bur distal (caudal) to the canine tooth that permits elevator purchase to aid in loosening the root. Long oblique releasing incisions on the buccal side should be avoided in this area because of the risk of injury to the mental nerves and blood vessels.

Technique tip: A lingual envelope flap is the best way to approach the mandibular canine. It will permit significant bone removal in a "safe" area allowing controlled elevation.

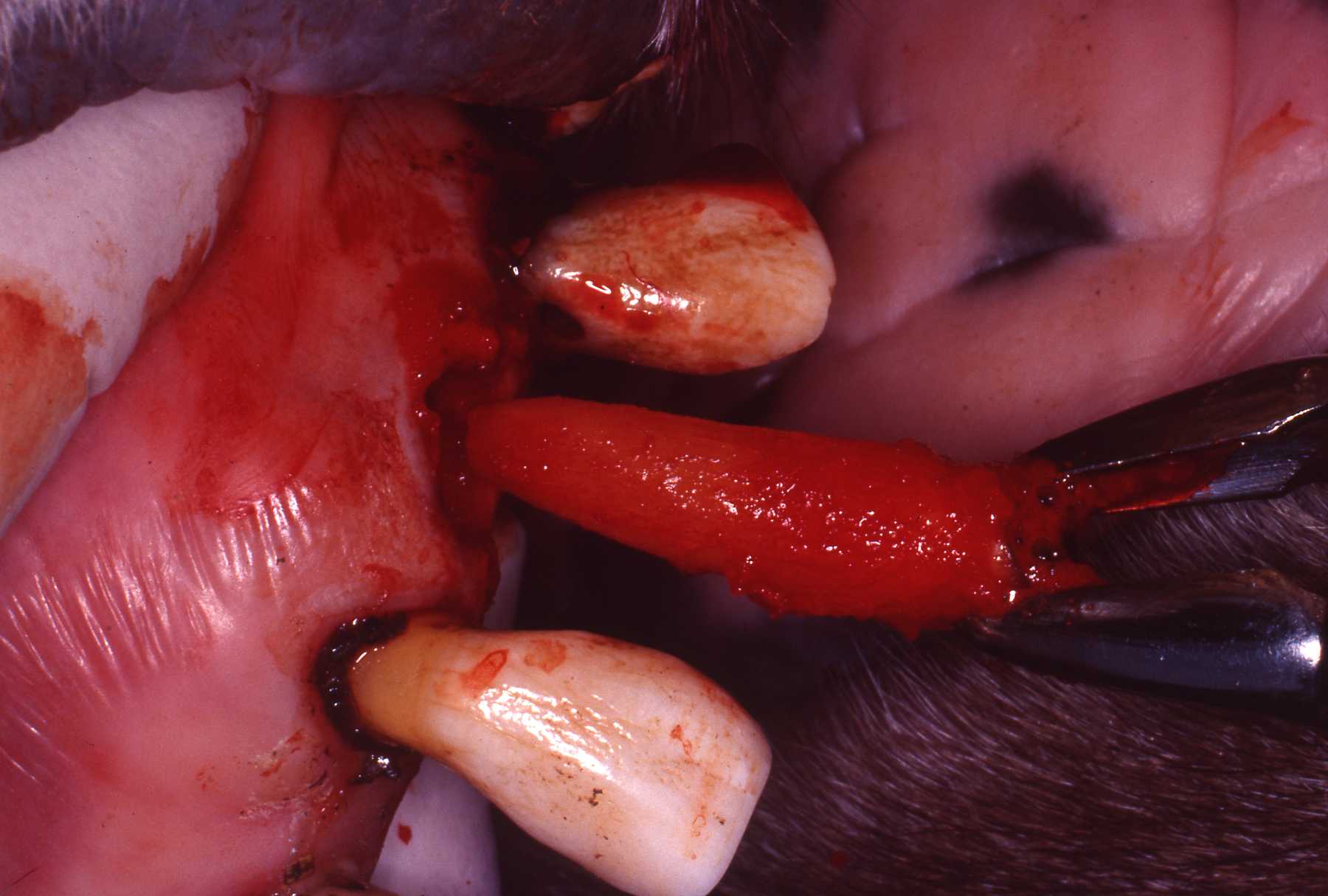

An exception to the rostrally directed flap design is that used to extract the maxillary third incisor and canine tooth. Because of the caudal extension of the roots of these teeth, a caudally directed flap minimizes the size of the flap while still providing adequate exposure (Fig 9).

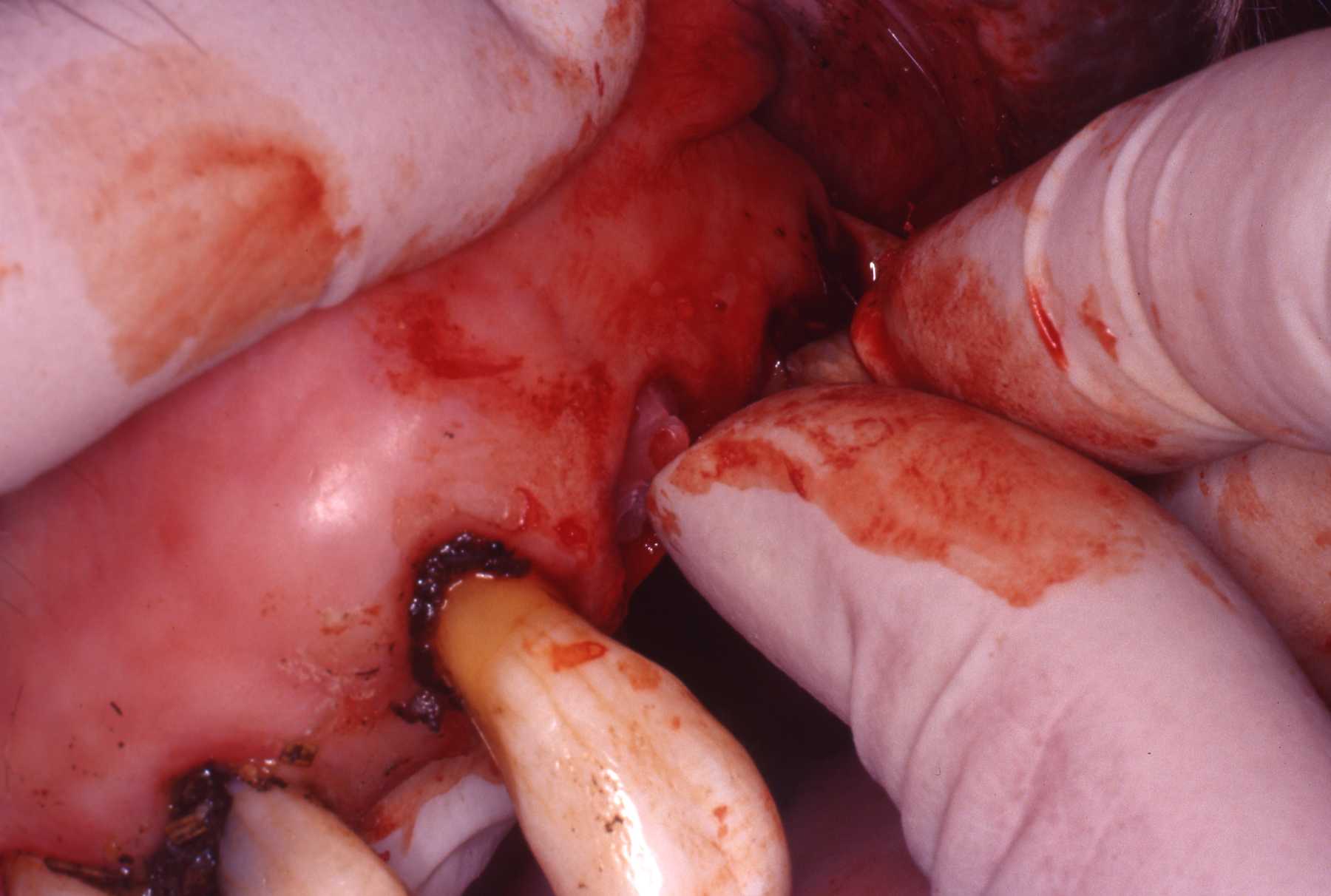

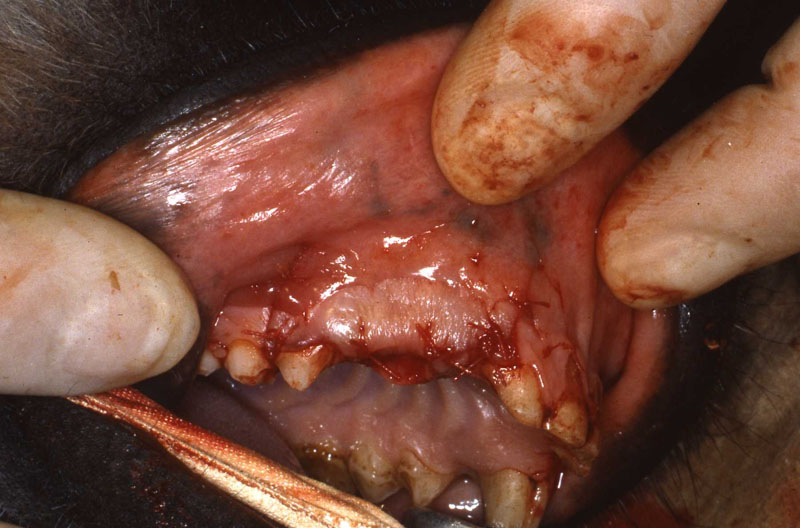

Figure 9

Figure 9

The alveolar bone is removed over the buccal side of the root with a handpiece and dental bur. The bone overlying the lateral aspect of the root can be entirely removed or a trough of bone can be removed along the outline of the tooth approximately one third to one half of the root's length. Shallow grooves are cut in the bone using a dental bur on the rostral and caudal aspects of the tooth to permit adequate placement of an elevator tip. These grooves must reach the full 180 degrees opposing one another. An elevator or luxator is utilized to break down the periodontal ligament. The elevator is rotated until the periodontal ligament is sufficiently loosened. The tooth can be luxated laterally; however, the tooth must not be radically tipped in a lateral direction because the apex of the root may be forced medially into the nasal cavity. Dental elevators and extraction forceps can be used alternately as well.

The same technique can be used to remove the bone overlying the lateral aspect of any root. If a dental handpiece is not available, the osteotomy of the overlying alveolar bone can be accomplished using small osteotomes or chisels specifically designed for this purpose. After tooth and root surgical extractions, rough bone edges are smoothed with the dental bur, a bone rasp, or ronguers. During alveoloplasty with a dental bur, cooling with sterile water or saline is necessary to dissipate heat generated by the bur to avoid subsequent bone necrosis.

Each tooth that is extracted should be inspected closely to ensure that the entire root has been removed. Retained roots of abscessed teeth must be retrieved to prevent the formation of a chronic draining tract. Retained roots subsequent to traumatic loss of the crown with no associated infection have been left in situ without complications. A surgical approach to a broken root is recommended; however, a handpiece and dental bur can be used to pulverize the retained root within the alveolus as well. The author emphasize that great caution should be exercised when using the dental bur to disintegrate a retained root tip because adjacent structures such as the maxillary sinus or mandibular canal easily could be penetrated. Emphysema from the high-speed air-driven handpiece is also a concern. Removal of excessive alveolar bone can cause structural weakness resulting in mandibular fracture. The extraction site should be thoroughly examined to ensure the entire root has been removed. If necessary. radiographs can confirm root removal.

This page:

Techniques

Page 1: Introduction, Indications, Morphology

Page 3: Postoperative Care, Extraction of Feline Teeth, Summary