The Zoo Health Care Team

Many zoos have a veterinary staff that deals with hundreds of species. My experience working with zoo veterinarians and their staff has been an immense privilege. The range of veterinary medical care they provide boggles the mind. Just the challenge of diagnostics is phenomenal.

Zoo animal management and medicine has become so sophisticated that the animals living in zoos often live much longer than their wild counterparts. Therefore, zoo populations are often considered geriatric. Indeed, if we keep these animals captive, we owe it to them to maintain their health and comfort as they serve as ambassadors for their wild relatives and environments.

Professional zoo keepers are the first line of daily health care. They play a large role in their daily routine, noting any signs or changes in animals' habits which might indicate a medical concern. Signs of dental or oral disease that zoo keepers must be looking for include the following:

When the veterinarian decides that there is a significant issue, they may consider intervention. This frequently requires a sedation or general anesthesia in order to do an exam, gather information and provide treatment. If a dental or oral problem appears to be present, the dental consultant is included in the team.

The one area that zoo veterinarians master is that of general anesthesia. The logistics of dealing with the various types and sizes of animal patients present complex challenges. This process includes all the considerations of the physical confinement of the patient in order to initiate an anesthesia, through recovery. Safety of the patient and the zoo staff is of paramount importance. The success of any procedure is predicated on a successful anesthesia.

Collaboration with the Zoo Health Care Team

In most states in the US, it is illegal for a dentist to treat animals, unless under the direct supervision of a veterinarian, as it should be. The zoo veterinarian is in charge of veterinary procedures. Zoo curators and directors may have some degree of influence in veterinary care decisions.

General anesthesia parameters determine procedure time limitations. These include the unique challenges of a safe initial sedation, including consideration of the patients' enclosure situation regarding controlling the patient. Then the veterinarian must consider the inherent physiological risks of general anesthesia. These challenges will determine the opportunities for long, multiple or follow up procedures. They frequently dictate where examination and treatment procedures can be performed also. The dental consultant will also be challenged by these situations to provide diagnosis and treatment.

During the procedure, the dental consultant and anesthesiologist (veterinarian) must be in constant communication. Usually a third individual, veterinarian or veterinary technician is closely involved monitoring the patient and managing IVs etc. The animals' depth of anesthesia must be maintained for its safety and the safety of the operator. Any movements or changes in jaw tension should be continually discussed. Constant communication regarding all aspects of the ongoing procedure will result in safe and successful outcomes.

Treatment Choices

All the considerations of actual operative treatment choices will be unique to each case. Examination, diagnosis, deciding whether treatment is justified and prioritizing multiple issues presented, must be done promptly when safe general anesthesia is achieved. Again, the opportunity to follow up will be limited, therefore the most definitive treatments must be chosen.

Infection is of course the most important condition to address. Teeth that are obviously painful or at risk to become infected or painful must also be addressed. Having the benefit of treating human patients that describe their discomfort, relative to dental and oral pathoses, I am confident that my animal patients are experiencing the same symptoms. Although they may appear stoic, animals attempt to socially hide their pain so as not to appear weak or impaired.

My philosophy toward treatment choices has evolved to become very conservative for some pathoses, and very aggressive for others. Working closely with experienced veterinarians we have developed this philosophy together. Some species of captive exotic animals' lives are not as critically dependent on their dentitions' as they would be in their wild environment. For others they are just as critical, those are the ones which must be addressed very aggressively.

Herbivores, in particular ruminants for example, must be able to masticate their food in order to digest it to survive. Most primates and carnivores can be fed food in compositions that do not have to be chewed and they will be able to digest and survive. Therefore, extraction of herbivores posterior teeth is only done when absolutely necessary. Particular teeth, such as mandibular canines and carnaissals in carnivores are especially important to their jaws physical integrity. Therefore, endodontics will be seriously considered to maintain them. Of course there are always exceptions to consider. I review animal groups and particular species relative to these treatment considerations in another section.

I usually only consider relatively simple procedures or restorations on animals. If I can simply polish smooth a sharp or rough enamel fracture, I will do that rather than place a restoration. Functional durability is my only consideration of restorations in animals.

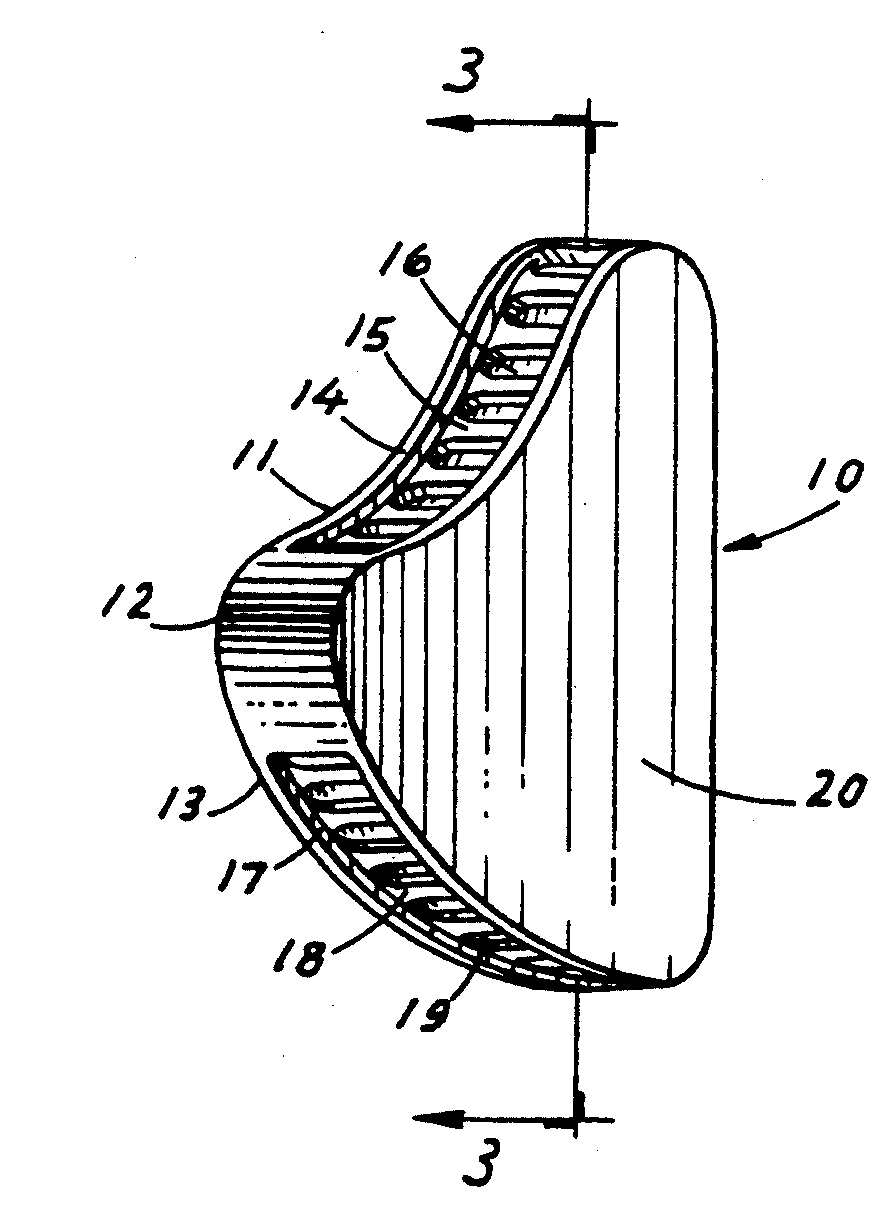

I have placed full cast crowns on dogs trained in law enforcement. I have provided crowns that remained in place for the remainder of the dogs' career, permitting challenging duty functions. Other than on law enforcement dogs, my philosophy toward performing the multiple anesthesias (or a very long single anesthesia) required to provide a crown would only be warranted in a very few situations. These would be considered on a domestic or captive exotic animal canine or perhaps a carnaissal tooth that has had an endodontic prodecure on a relatively young animal. I have observed endodontically treated teeth in such animals fracture after several years. They became infected and had to be removed. A conservatively shaped full cast crown would serve well to avoid this complication.

Preparation to Diagnose and Provide Treatment

Currently at Milwaukee County Zoo we have an excellent hospital and full range of dental equipment which enables us to effectively provide treatment. It was not always that way!

My first examination of an exotic animal was while zoo keeper Sam LaMalfa held "Trick", a young orangutan, for me and the veterinarian, Dr. Bruce Beehler. Treatment was performed a couple days afterward, in the evening, in the exhibit hallway. I extracted two mandibular incisors which had been displaced in a fall. We used a flashlight and a few extra instruments from my dental practice and our zoo kit was started!

Prior to treating a specific animal, the operator must review the anatomy to be encountered. Today this is much easier with many resources on the internet. However, physical specimens of skulls with intact dentitions are the best aid. Over my tenure at MCZ we have developed relationships with regional museums to acquire such specimens. Designated animals from our collection that die are prepared into reference specimens for us to keep or have accessible.

Paleontological reference texts are among the best dental formulae and anatomical resources. Because teeth are the longest surviving physical remains of a mammal, paleontologists have studied and documented them exquisitely. However, they don't reference teeth root anatomy which is so critical to dental treatment.

The developmental and functional physiology of dentitions is also very important information in consideration of treatment. These will require researching various sources including natural history reference texts and the academic literature. In recent years detailed information of this type for equidae has become available, driven by the developing veterinary specialty of equine dentistry.

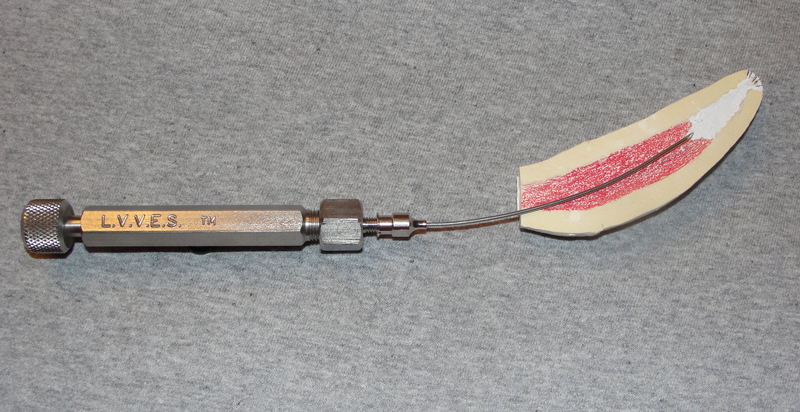

An example of utilizing a skull specimen for treatment planning is to become familiar with accessing the apex of a canine when an apisectomy/retrograde fill endodontic procedure is appropriate.