Primates

Dentists will recognize the primate dentition gross anatomy as similar to their human patients. Veterinary dentists will have to do some preparation to become familiar with it. The specific anatomical variations of the coronal portions of the teeth of the various species are only of modest treatment concern. However, the anatomical variations of root configurations are more significant. These should be reviewed whenever possible to prepare for extraction or endodontic treatments. The types of pathosis encountered will be fundamentally the same as in other mammals.

Use references such as those listed on this site. Radiographs of the particular species are very helpful. Skull and teeth collections are the optimum for preparation. I have encouraged accumulating a collection at our zoo and we have established an archive from animals that died at Milwaukee County Zoo. Over the years I established a relationship with the Milwaukee County Museum and the Zoological Museum at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. They receive the carcasses of our animals after pathologists evaluate them. Then the animals' skeletons are added to their or our collection.

The apes will have the same number of teeth as humans. That is 20 primary teeth and 32 permanent teeth. The same is true for the old world monkeys. Some new world monkeys have three premolars per quadrant. Other primate groups have various dental formulae. The primate teeth are anelodont with very few exceptions (aye-aye for example). There are also variations in numbers of roots. Therefore, again, preoperative radiographs should always be reviewed prior to extraction or endodontic procedures. The root apices usually have single orifices with a small percentage having auxiliary canal openings or perhaps two apical openings as often found in humans.

The primates were traditionally described in two suborders: "Prosimii" and "Anthropoidea". More recently the primates have been taxonomically divided into two major groups. One is the Strepsirhini which includes Lorisiformes and Lemuriformes. The second is the Haplorhini placing the tarsiers with the monkeys and apes (anthropoids). See the outstanding text Mammal Teeth by Peter S. Ungar and Colyers' Variations and Diseases of the Teeth of Animals.

The most common dental pathosis that I have encountered in zoo primates is traumatic injury to the anterior teeth. The prominent canines and incisors are fractured during fights, falls and interactions with enclosures and "enrichment toys". The zoo staff should always be thinking "What can go wrong with this enclosure structure or toy?" Because, if it can, it will. When I began working with the zoo, the enclosures usually had very hard tile or concrete floors. These made cleanup easy but did contribute to injuries. Over the years, enclosure designs have been improved, reducing injuries.

Gorilla Linda: Parotid Gland Infection

Adult female gorilla “Linda” presented with significant swelling of her right parotid gland. By the day she was sedated and anesthetized for examination and treatment, the infection had burst open through the skin with a purulent discharge. Intraoral exam revealed the inflamed Stensons duct region. Cloudy discharge was also evident in the duct. Dr. Vickie Clyde carefully debrided the gland area and sutured a penrose style drain to the wound. Samples of the draining materia were acquired for culture and with appropriate antibiotic therapy the infection did resolve.

Gorilla Nadami: 13 year old female maxillary canine endodontic procedure

During physical examination fractured maxillary right canine was noted. Chronic fistulos tract noted at junction of attached gingiva and buccal mucosa. Considering age of animal and fact that infected canine pulp had abscessed to the point of forming the drainage tract. I was concerned that the pulp canal would be quite large and that the root apex might be open, not constricted. An open apex would present a challenge to establish a solid stop for a good endodontic fill. Fortunately we did find a solid stop at the apex, permitting a solid fill.

Fistulous chronic drainage tract, found during physical examination, at junction of attached gingiva and buccal mucosa

Fistulous chronic drainage tract, found during physical examination, at junction of attached gingiva and buccal mucosa Fractured maxillary left canine exposed pulp canal

Fractured maxillary left canine exposed pulp canal Preoperative radiograph. Note large diameter canine root canal in this young animal

Preoperative radiograph. Note large diameter canine root canal in this young animal Endo access opening

Endo access opening Pulp canal debrided with files, irrigating with NaOCl and RC Prep

Pulp canal debrided with files, irrigating with NaOCl and RC Prep Working length radiograph, 40 mm

Working length radiograph, 40 mm Canal dried with paper points and sterilized pipe cleaners

Canal dried with paper points and sterilized pipe cleaners After master cone fitted, canal filled with PCA sealer paste via PCA Pressure Syringe technique. Gutta percha points then placed and condensed

After master cone fitted, canal filled with PCA sealer paste via PCA Pressure Syringe technique. Gutta percha points then placed and condensed Endo fill radiograph

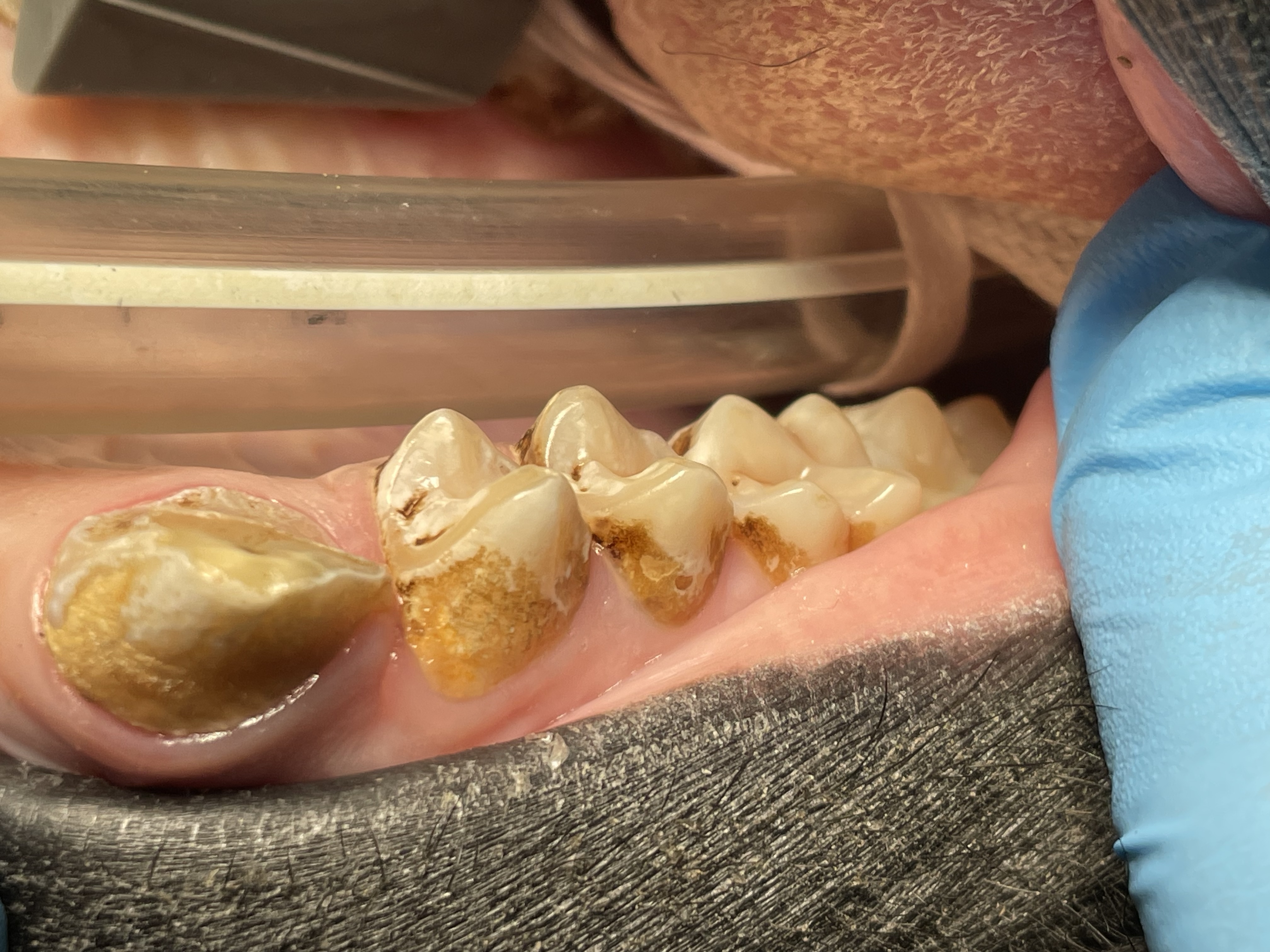

Endo fill radiograph Enamel erosion throughout dentition due to chronic regurgitation/ingestion behavior

Enamel erosion throughout dentition due to chronic regurgitation/ingestion behavior Enamel erosion throughout dentition due to chronic regurgitation/ingestion behavior

Enamel erosion throughout dentition due to chronic regurgitation/ingestion behavior

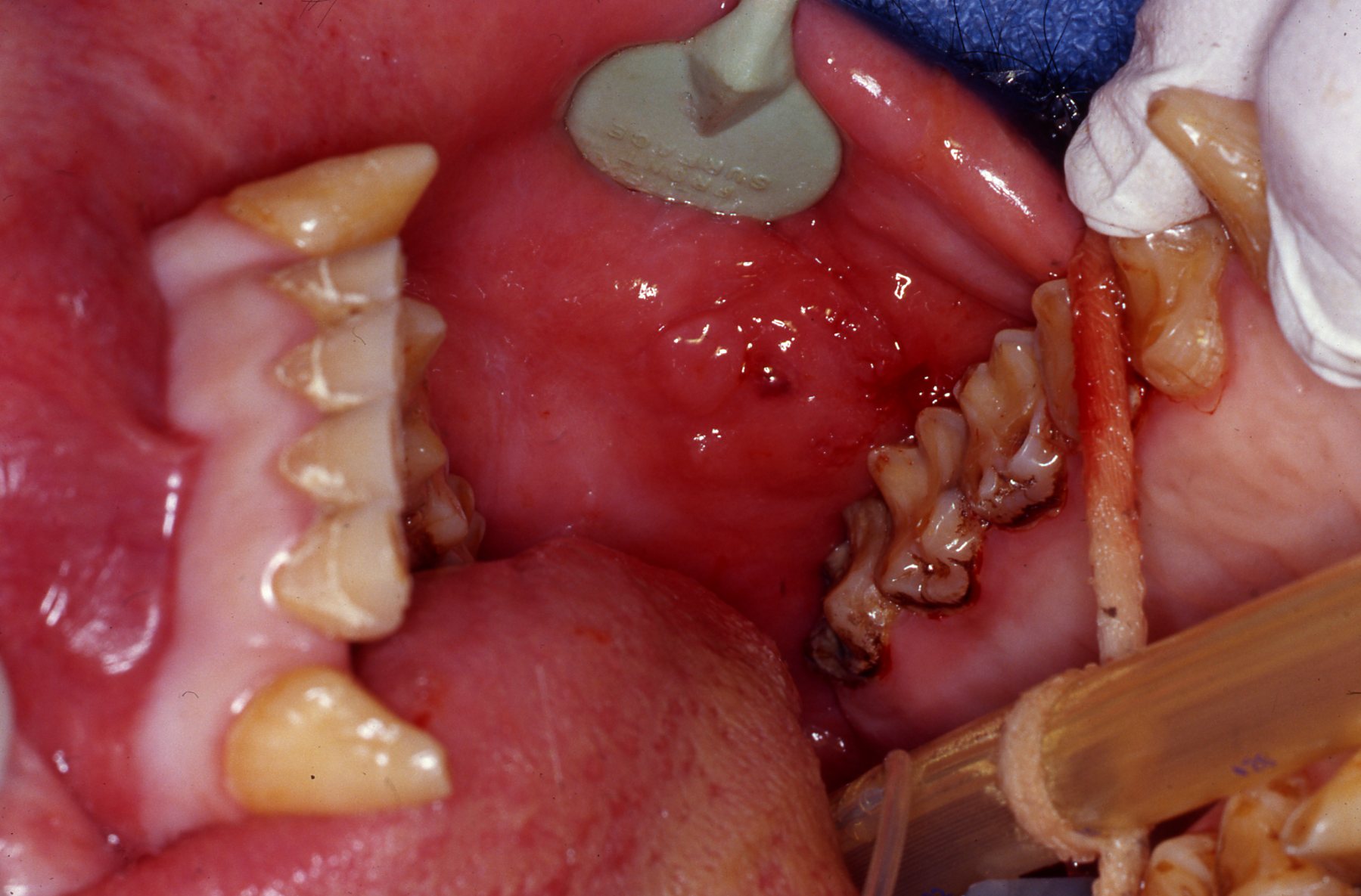

Bonobo Makanza: Extraction of two fractured incisors' residual roots

February, 2015Milwaukee County Zoo.Photos by Mark Scheuber, Zoo Keeper/Photographer

Maxillary left central incisor and lateral incisor residual roots. Region was inflamed, edematous prior to two weeks of antibiotic therapy.

Maxillary left central incisor and lateral incisor residual roots. Region was inflamed, edematous prior to two weeks of antibiotic therapy. Conventional dental film in position. Digital Phos Phor plates were also exposed.

Conventional dental film in position. Digital Phos Phor plates were also exposed. Dr. Hausmann and Dr. Scheels positioning Nomad radiography unit.

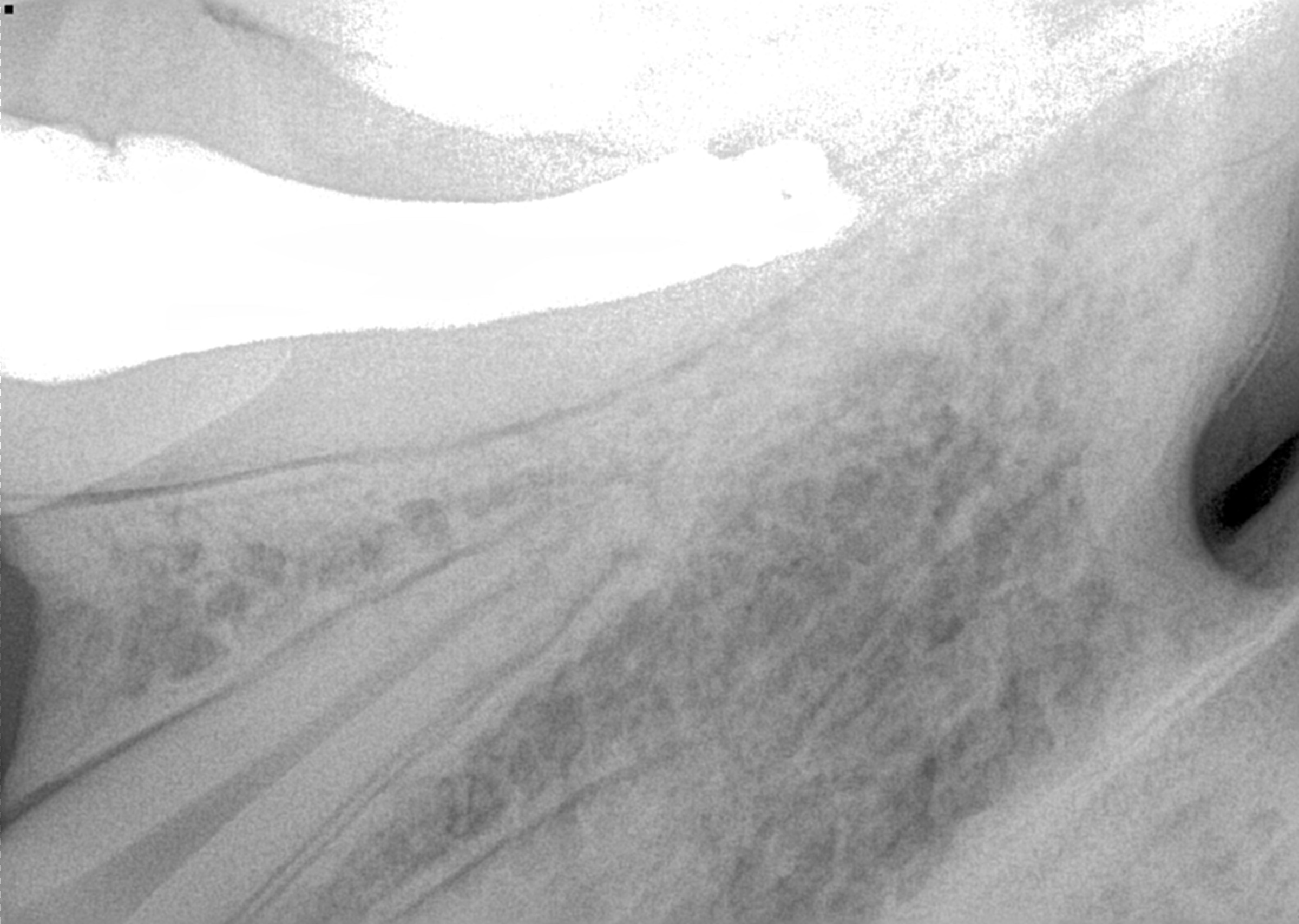

Dr. Hausmann and Dr. Scheels positioning Nomad radiography unit. Digital image reveals periapical lesion on central incisor residual root.

Digital image reveals periapical lesion on central incisor residual root. Incision on crest of ridge.

Incision on crest of ridge. Luxator technique utilized to remove residual roots.

Luxator technique utilized to remove residual roots. 556 surgical bur used to remove approximately 2mm. of alveolar bone surrounding each root ("ditching".)

556 surgical bur used to remove approximately 2mm. of alveolar bone surrounding each root ("ditching".) Alveoli after roots extracted

Alveoli after roots extracted Extracted roots

Extracted roots Simple interrupted sutures placed with knots inside the wound so that Makanza will find it difficult to disturb them with his fingers and tongue.

Simple interrupted sutures placed with knots inside the wound so that Makanza will find it difficult to disturb them with his fingers and tongue.

Bonobo Ricky with fractured central incisor. Endodontic therapy, composite resin restoration. Supernumerary maxillary right premolar. The supernumerary caused root resorption of no. 105. 105 was also extracted.

Photos by Mark Scheuber, Zoo Keeper/Photographer

As with all the captive animals, zoo keepers are the first line of health care. Any facial swelling, fractured teeth or changes in eating habits are signs that may indicate dental or oral disease and should be reported. Obviously, observation of a fractured tooth warrants a dental exam including radiographs. As always, just "watching it" can only to lead to significant problems. Usually these injuries are not noticed right away. As noted elsewhere, the animals will naturally try to hide pain or illness. And often, the initial injury discomfort will dissipate as the natural process of the body dealing with the injury progresses. Secondarily, the injury will lead to more severe involvement and infection.

In many primates, the pulp chamber is very close to the crown tip, compared to humans. The long maxillary canine root apices of many primates are located just beneath the eye. Besides swelling, one of the most common signs of dental abscess is a chronic drainage tract on the face, just below the eye, over the root apex. Lesions in that location are indications of probable canine tooth abscess. These lesions can reach to the eye orbit region. I have also encountered a number of abscessed maxillary lateral incisor and canine abscesses in my human patients that reached the orbit region. Hence the old name "eye tooth" for maxillary canines.

As mentioned above, the canine roots are proportionately very long and often require flap reflection and bone removal to extract them. Therefore I prefer to save pulpal abscessed canine teeth with endodontic therapy.

Periodontal Disease

The next most common pathosis encountered is periodontal disease. Again, improvement in diets has reduced this disease. I strongly believe that besides nutrients, diet texture is very important in optimizing oral health, minimizing periodontal disease. I believe that soft or pelleted foods that do not stimulate and challenge the dentition and periodontium may contribute to periodontal disease. Duplicating natural diets in this manner for diverse species is of course, not always possible, but zoos do make efforts to do so when they can.

In the gorillas and bonobos that were born and raised here at Milwaukee County Zoo, we have not had many periodontal problems. We have had adult gorillas come to us from other zoos with significant periodontal disease.

Most or our orangutans however, have had chronic, serious periodontal disease. All of our males have eventually lost all their teeth due to periodontal disease. That has not been the case with the females. We are not the only zoo that has had the chronic periodontal problems with orangutans. See Dr. Norm Stollers' paper: In the typical orangutan case that I have dealt with, there is not much accumulation of plaque or calculus. However, deep periodontal pocketing and bone loss progresses until the teeth become very mobile. I have not observed much bleeding in the most severe of these cases. We discussed preventive strategies and even tried chlorhexidine gluconate rinses to subdue the disease process. However, the orangs did not accept the products, probably due to the taste.

I believe that there is very likely some genetic component to the periodontal disease prevalence in our orangutan lineage. Most of them that we have had are crosses of Sumatran and Borneo genetic lines. And again, with what I have been able to learn about their wild diets is that it is very different than what can be offered in captivity in this part of the world.

I frequently encountered caries in many animal groups when I began serving as a consultant. Until the early 1980s comprehensive veterinary care was not commonly provided in zoos, so physical and cursory oral and dental exams were only done when significant problems were already present. Proper diets had not been researched and keepers often provided their charges with sweet treats that led to tooth decay. Fortunately, zoo diets are scientifically developed now and keepers know to not provide improper treats.

I have also encountered significant dental attrition due to bruxism in many primate species. The psychological stress of confinement certainly contributes to such habits. Again, zoo keepers are very aware of such issues and these are addressed in many effective ways. Another habit related to stress, regurgitation of food and reingesting it, causes very significant damage to the entire periodontium, leading to loss of teeth. See Dr. John Huffs' on treating Tino at Salt Lake City zoo. I examined Tino when he was young at our zoo. He already had the regurgitation habit then.

We have also encountered anatomic variations and anomalies in several species such as supernumerary teeth and impactions. Again, knowing the "normal" situation and always taking preoperative radiographs is necessary to recognize such situations. Such variations and anomalies do not necessarily warrant treatment unless they are causing or will very likely lead to pathosis.

Primate Dental Anomalies

Tommy Orangutann, young adult, impacted mandibular premolar case

Bonobo Maringa Case

Ramar, Silver Back Lowland Gorilla

Brookfield ZooOral antral fistula, xenograft repair. The repair was done by Dr. Patrick Mooneyham, oral surgeon. I served as his assistant. I performed the canine endodontic procedure.

Ramar, silverback lowland gorilla, Brookfield Zoo

Ramar, silverback lowland gorilla, Brookfield Zoo

Exam: Fractured maxillary left canine (no. 15 or 207), extraoral chronic drainage tract adjacent to nostril and oral antral fistula where maxillary second molar had been extracted by veterinarian

Exam: Fractured maxillary left canine (no. 15 or 207), extraoral chronic drainage tract adjacent to nostril and oral antral fistula where maxillary second molar had been extracted by veterinarian

Fractured canine with exposed pulp cavity

Fractured canine with exposed pulp cavity

Radiograph of canine

Radiograph of canine

Canine endo fill

Canine endo fill

Canine endo amalgam restoration

Canine endo amalgam restoration

Fistula

Fistula

Radiograph of fistula

Radiograph of fistula

Fistula explored

Fistula explored

Fistula exposed

Fistula exposed

Fistula being repaired

Fistula being repaired

Fistula exposed, tensionless flap

Fistula exposed, tensionless flap

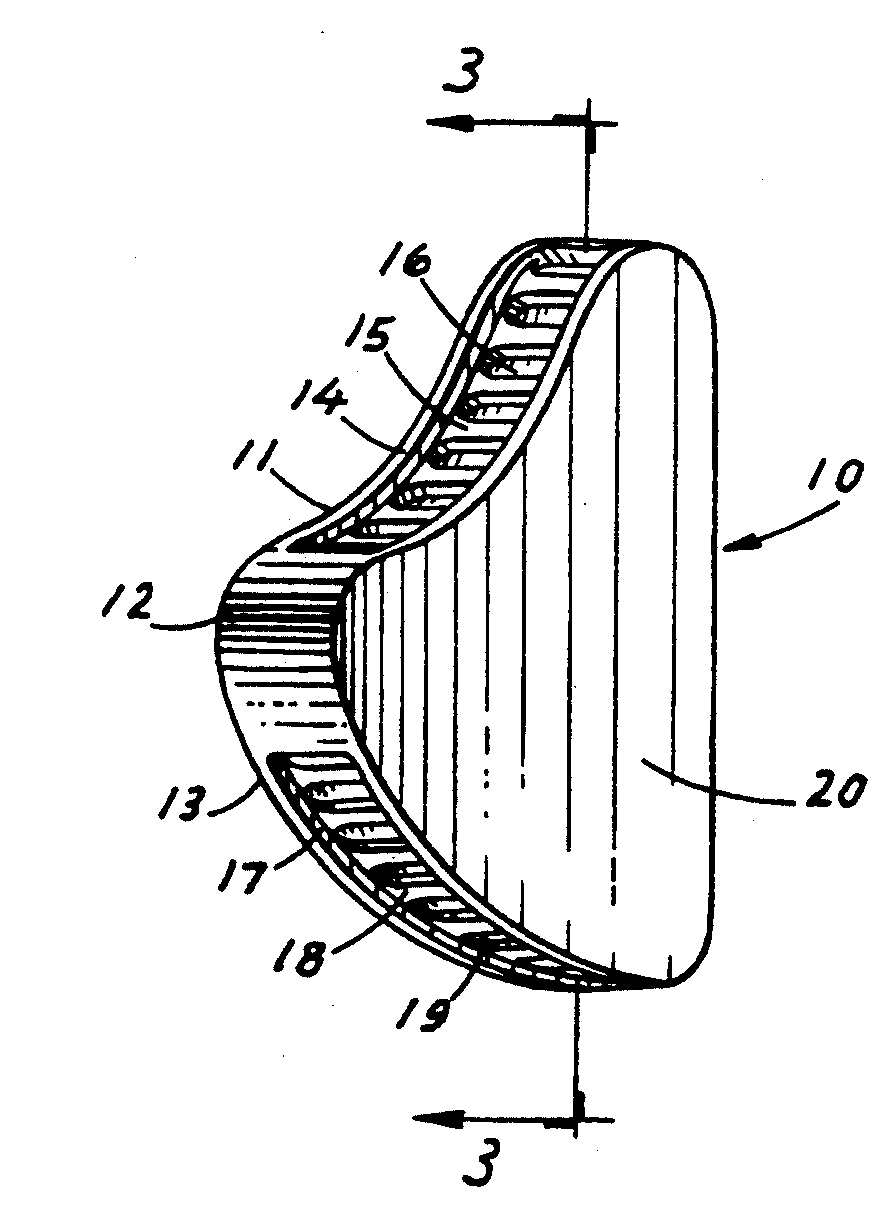

Diagram of section through the fistula

Diagram of section through the fistula

Diagram of fistula closure technique: Layers of gelfoam on sinus and oral sides of human cadaver bone crystals

Diagram of fistula closure technique: Layers of gelfoam on sinus and oral sides of human cadaver bone crystals

Flap closure

Flap closure

Follow up exam of fistula repair

Follow up exam of fistula repair

Radiograph of bone repair three (?) months post op

Radiograph of bone repair three (?) months post op

Canine endo follow up

Canine endo follow up

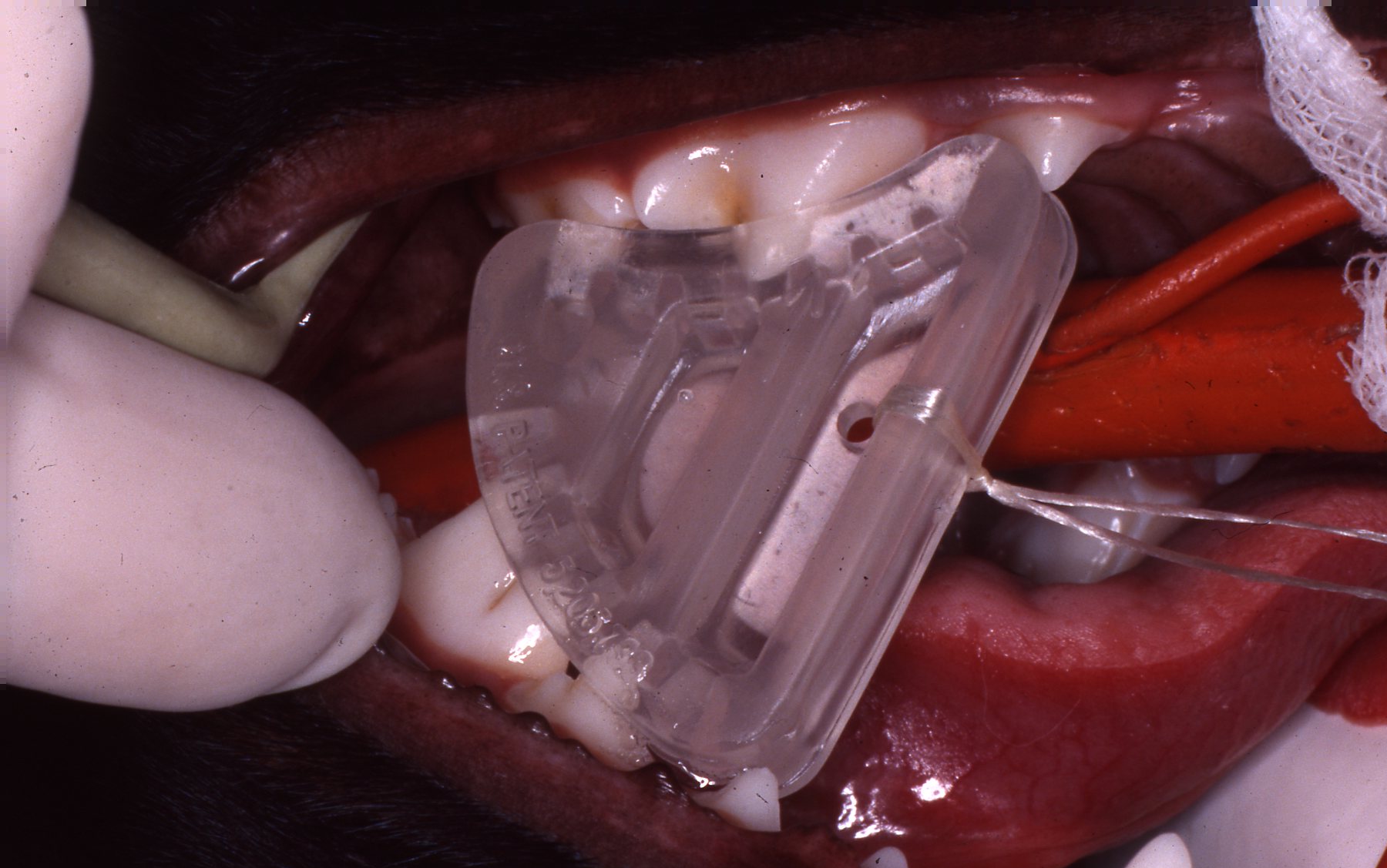

THE WEDGE®

Radiolucent Mouth Prop for Dogs and Cats

- Anatomically designed to provide secure, open mouth

- Use for anesthesia, radiography, oral surgery, and dentistry

- No moving parts, use if canines are absent

- Ultrasound, heat, or cold sterilize

- SMALL size for cats and smaller dogs, LARGE size for medium to large dogs

NOTICE: Veterinarians have used spring-loaded mouth "gags" in cats and dogs for many years. However, the spring-loaded devices are no longer recommended. A study published in THE VETERINARY JOURNAL (2014) showed that the spring-loaded "gags" generating constant force contributes to bulging of the soft tissues between the mandible and the tympanic bulla in cats. This force leads to the compression of the maxillary arteries as they course through the osseous structures. In cats the maxillary arteries are the main source of blood supply to the retinae and brain.

Reduction of the blood flow can result in temporary or permanent blindness and neurologic abnormalities. Spring-loaded "gags" constant force can also cause jaw muscle strain and injury to the temporomandibular joints.

It is recommended to use "static" mouth props such as the WEDGE. Be sure to not open the jaw to its maximum to avoid muscle strain and temporomandibular joint injury.

The WEDGE® is a one-piece, radiolucent mouth prop. The patented, anatomic design holds the carnivore mouth open during anesthesia by securely engaging the premolars and molars.

The WEDGE®:

- Replaces the metal "gag" which catches whiskers and gloves on springs and slides.

- Has no grommets to be lost, permitting metal to enamel contact.

- Can be used if the canines are broken or absent.

- Can be used on either side of the mouth and switched quickly.

- Radiolucency facilitates clear open-mouth radiography.

- May be ultrasounded and heat or cold sterilized.

- Has a hole provided for attachment of a safety lanyard if desired.

- Is useful during anesthesia, intubation, oral examination, oral surgery, dental procedures, and radiographic examination.

Developed and patented by Dr. John L. Scheels, dental consultant to the Milwaukee County Zoo, Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine.

"The (Scheels) Veterinary mouth prop's biggest asset is its simplicity - open the mouth and stick it in!...it does not interfere with radiographic detail, can be ultrasounded, and autoclaved...can be used for dental and oral surgery procedures...is positioned within the mouth, unlike the spring loaded (extra-oral) devices which can be in the way of the operator and interfere with positioning the patient..."

~ Paul E. Howard, D.V.M.,

Vermont Veterinary Surgical Center, Burlington, Vermont.

Order The WEDGE® from any of these veterinary equipment suppliers:

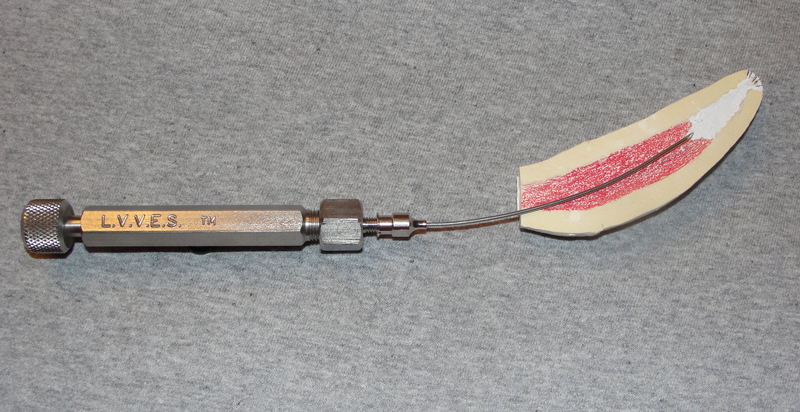

L.V.V.E.S

Large Volume Veterinary Endodontic Syringe™

Click here for more details

An endodontic syringe developed by Dr. John Scheels specifically for veterinary use in all species for complete and consistent obturation of root canals over 30mm long or with large pulp chambers. It permits the positive deposition of endodontic sealer and filler pastes at the apex of these long teeth. NO SPECIAL NEEDLES are required as it may be used with any standard size hub. Plastic, metal, threaded or non-threaded needle hubs will seal well on the tapered syringe nipple.

To purchase LVVES, contact Dr. Scheels directly at scheelsdds@sbcglobal.net.