Mastications

Personal observations and opinions

Topics

Local anesthesia

I use local anesthesia on my human dental patients but am not inclined to use local anesthesia on my veterinary dental patients. We always remind human patients to wait to eat until the anesthesia has subsided. Always. And we instruct our young patients' parents to monitor their children to avoid any rubbing, scratching or biting of their numb mouths. Despite these instructions, I have had numerous human patients of all ages bite their lips, cheeks and tongues while the local anesthesia persists. Several have had to return for suturing!

I have had several veterinarians tell me that they have had their domestic animal patients injure their mouths when they awoke from general anesthesia while local anesthesia persisted. Domestic animal patients are certainly easier to monitor and intervene with compared to the zoo patients.

But, "Never say never". I have used local anesthesia in some cases, especially for apes to avoid pain during a procedure and to allow for a lighter state of general anesthesia during the dental procedure. These situations are thoroughly discussed at the time and the veterinarian and keepers are particularly watchful during recovery to do what they can to discourage self injury by the patient. I am more confident using the local anesthesia on these larger primates because of their similarities to my human patients of course.

Diet/ Enrichment toys/ hard bones for carnivores etc.

The dental consultant can contribute to the husbandry of zoo animals by becoming aware of their natural history, especially their diets. Beside the chemical nutrition of their diets, the form and texture of their diets is very significant regarding the health of the teeth and periodontium. We must consider that captive wild animals do not have to spend all their waking moments seeking food or avoiding predators. They often have idle time that may lead to causing themselves some problems. Zoos make great efforts to keep their animals psychologically engaged to keep them stimulated and avoid what may be harmful activities. Enrichment toys for carnivores to play with for example, must be carefully considered. A very common mistake has been giving carnivores hard bones or the synthetic equivalent.

Carnivores do not chew on hard dry bones in the wild. They don't even chew much on bones on fresh kills. Rodents commonly chew on shed antlers for the minerals in them and sometimes on bones. The wild outdoors have old dry bones lying all around on the ground but carnivores do not chew on them. Even hyenas and such scavengers do not chew on old hard dry bones. Take the opportunity to observe what parts of a prey animal is eaten by the predator or scavenger. This can readily be done by observing a roadside deer kill if coyotes or other scavengers find it. There are many You Tube videos of carnivore kills and subsequent feeding, including hyenas. The soft internal organs are what is eaten first. Then muscle tissue. Fresh kills are usually thoroughly cleaned. Some cartilage and connective tissues will be incidentally consumed with the meat, but the large bones will remain. Fresh bones can be easily cracked by the "anvil" premolars of hyenas for the marrow. And they may do that on fresh bones when competition for food is at a high level. But eventually the hard dried bones will be abandoned. Other carnivores rarely spend much time on even fresh bones other than to clean off muscle scraps.

I recall first learning about carnivore natural feeding habits, on a smaller scale, from mixed practice rural area veterinarians when presenting CE dentistry courses at the University of Wisconsin, School of Veterinary Medicine. They reported that if a family brought in their house cats, which were fed prepared foods, and a couple barn cats that they were able to catch up, the barn cats who fed on mice had perfectly healthy dentitions, while the house cats had heavy calculus buildup and gingivitis. Therein started my interest in learning what I could about what and how my zoo patients eat in their natural environments.

I feel it is acceptable and wise to feed larger predators oxtails (cow tails), fresh or fresh frozen (fed after thawing) from the local beef processing plant. If they can be provided with the skin on, all the better. The smaller tail bones, cartilage and meat are an excellent combination to keep the teeth clean and stimulate the gingiva. Not all the captive large carnivores will eat the oxtails, especially if they were not provided them from a young age. It has been documented that rawhide type chews do help keep carnivore teeth clean but many veterinarians advise against them because of the potential for large pieces to cause GI blockage. We do not permit hard bones, antlers or any other natural or synthetic items for our carnivores.

Example: Border terrier (5 years old, 22lbs.) fractured both of his maxillary fourth premolars (carnaissals) chewing on Nylabone toys.

We have encountered fractured posterior teeth in our moose. Some of the resultant abscesses and malocclusions caused great difficulty to masticate. They also lead to serious oral infections.

We were not aware of the seriousness of these problems initially because of no obvious signs until the situations were quite severe. Unlike the swellings commonly called "lumpy jaw" (see Herbivore section) in many other herbivore species, alerting us to dental or oral infections, the moose oral pathoses have not resulted in bony enlargement.

Dropping food, being very selective or eating very little volume were the first signs noted by keepers, even for serious moose dental problems. Chronic drainage tracts and fistulas have developed and these were also some of the first signs observed.

I believe that poor choices of browse may have been a major contributor to these dental fractures and subsequent problems. I read as much as I could find on moose browse and contacted the head of a comprehensive, long time moose natural history study effort in Minnesota. This consortium includes representatives from the Minnesota State Wildlife professionals, the University of Minnesota and others. Among the research sources is the thoroughly studied Isle Royale moose herd. They were able to provide us with the information we needed. We were providing browse that was much too large in diameter. It should not be any larger than a centimeter. Most should be much smaller than that. Captive moose that are provided larger branches etc. will chew on them and do damage. Many of our moose were orphaned as calves and had no adults to emulate when choosing foods.

Supplemental information: The U.S. FDA maintains this report as a reminder to pet owners about the potential problems associated with giving bone treats or turkey/chicken bones:

U.S. FDA Consumer Update - No Bones (or Bone Treats) About It: Reasons Not to Give Your Dog BonesEnclosures

Enclosures that had bolts, nails or other items that can be accessed have caused many captive animals to break their teeth on them. Wood, especially splintered plywood that animals have access to chew on has also led to many oral and dental injuries.

Radiography

Radiography is absolutely mandatory to perform effective dental or oral surgical treatment. In many zoos, sophisticated radiography equipment and techniques may not be available. That was certainly the case for many years at Milwaukee County Zoo. I found portable radiography units to borrow for early cases. I used rapid developer and fixer in metal cans and used red light bulbs in small utility or bathrooms to develop intraoral dental films.

We learned to use the zoo hospital table radiography unit with fine grain and mammography film for full head views that are fully adequate for dental treatment. Right and left obliques are taken at 45 degrees with the mouth open. With proper positioning, each film will isolate one mandibular arch and one maxillary arch. Then with maxillary and mandibular dorsal-ventral intra orals, one will be provided with complete views of the entire arch.

When I installed digital radiography in my dental practice we used our conventional dental film automatic developer at the zoo hospital for intraoral films.

We are now fortunate to have a Nomad portable unit and digital radiography capacity at MCZ for dental cases. This technology certainly improves our efficiency for treatment.

Feline Odontoclastic Resorptive Lesions

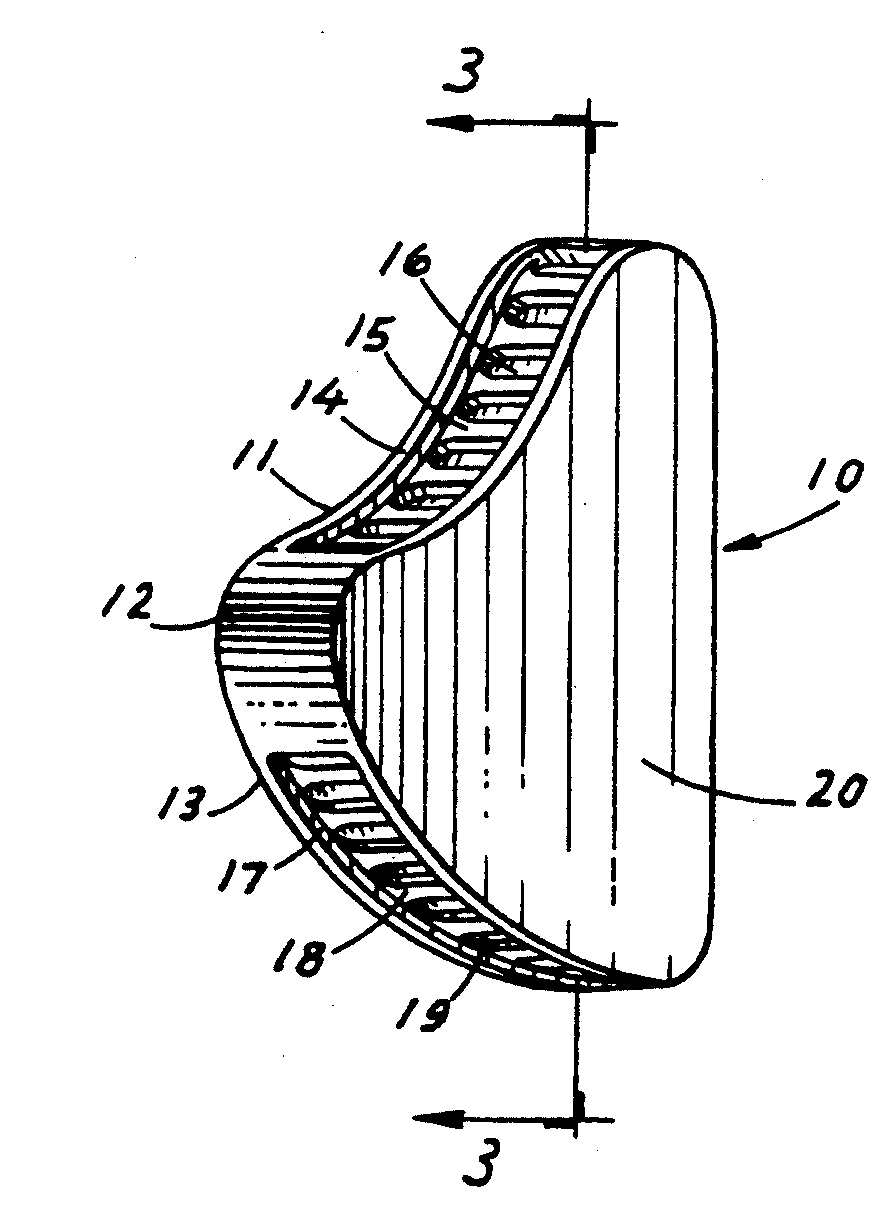

Felines exhibit a unique erosion at the cervical area called Feline Odontic Resorptive Lesions. These lesions appear to be associated with localized gingivitis. Many people have tried to explain why these lesions develop, however no one has come up with a definitive etiology.

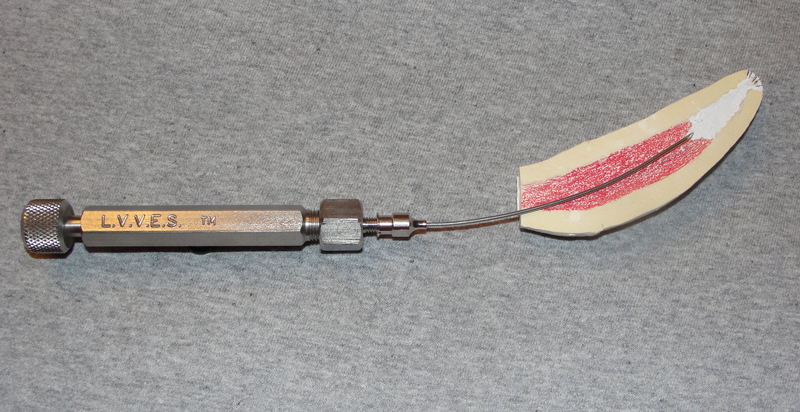

I have restored FORL lesions with silver amalgam with excellent long term effect in multiple feline species. The lesions have ceased to enlarge. Restoration attempts with composite resin will fail, erosion will continue. Regrettably, most dentists and veterinary dentists will no longer have silver amalgam and the necessary instruments available to use it.

In personal conversations with Dr. Thomas Clark at Louisville Zoo I learned that he also has had success with silver amalgam. The lesion must be prepared with inverted cone burs to establish mechanical retention. These restorations have held up without failure for many years, see photos.