Special Cases of Note

Special cases that are instructional and illustrativeof typical zoo dentistry cases

Bongo Ira

July, 1987Milwaukee County Zoo.Bongo female, “Ira” fractured her mandible through the cartilaginous symphysis when she panicked and ran into an enclosure wall. She had done this before, fracturing her mandibular incisors, which had been observed by her keepers. However, she had not been sedated for an exam by the veterinarians, in great part because of her skittish nature.

When she was anesthetized the night of this severe injury, July 4, 1987, it was apparent that the anterior segment of her mandible was infected because of the multiple fractured incisors and the infected bone had become severely weakened. Fortunately, the posterior segment of the cartilaginous symphisis was intact and still held the right and left mandible bodies connected. Zoo veterinarian, Dr. Bruce Beehler anesthetized “Ira” and we examined the fracture. With the help of a large animal veterinarian I used ligature wire to lift up the anterior segment, securing it to the still intact mandible symphisis. We understood that this was just a temporary fix. Soon after “Ira” was awake she began to feed and put downward pressure on the repair.

I enlisted the aid of veterinary surgeon Dr. Paul Howard from the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine. He came to Milwaukee County Zoo the next evening, July 5, with a surgical assistant and appropriate orthopedic equipment. After removing the ligature wire repair and debriding the wound he reduced the fracture securing it with six intermedullary pins. Extensive suturing was necessary to repair the damaged tissues. The pins held the reduction.

Over time some of the pins loosened and came out. However, the reduction held and the mandible healed in place with modest malposition and a slightly drooping lip. “Ira” lived for several years and had healthy calves.

Dr. Howard presented this case at the second Exotic Animal Dentistry Conference held in Philadelphia in 1989.

Howard PE, Scheels JL, Lenhard AL, Beehler BA. Repair of bilateral mandibular fractures in a Bongo. Journal of Veterinary Dentistry. 1989;6(3):15-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/089875648900600309

Bongo antelope normal anterior mandibular dentition and maxillary pad.

Bongo antelope normal anterior mandibular dentition and maxillary pad. Bongo “Ira” mandible symphysis fracture presentation.

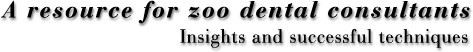

Bongo “Ira” mandible symphysis fracture presentation. Bongo “Ira” diagram of how intermedullary pins were placed to reduce fracture.

Bongo “Ira” diagram of how intermedullary pins were placed to reduce fracture. Bongo “Ira” Radiograph of remaining pins 6 months post-op.

Bongo “Ira” Radiograph of remaining pins 6 months post-op. Bongo “Ira” with calf, note drooping lip.

Bongo “Ira” with calf, note drooping lip.Siberian tiger mandibular canine endodontic procedure

October 16, 2014Milwaukee County Zoo. Transporting Tula photo by Mike Nepper

Transporting Tula photo by Mike Nepper"Tula" is a 2 1/2 year old Siberian tiger, weighing 242 pounds. She fractured her mandibular canine when playing with her littermate, sister, on an elevated structure. An observant zookeeper spotted the canine tip piece, approximately 1 1/2 cm. long, shortly after the incident and confirmed by observing the tigress, that the canine was short, fractured.

Tula did not seem to be in pain or distress and her behavior was normal according zookeepers. However, I am aware of fresh fractures of this type, exposing the pulp and nerve caused some captive carnivores to be in so much pain and distress that they attacked and killed a cage mate. ("Bubba", Brookfield zoo, year?)

Approximately ten days later, on October 16, 2014 the zoo veterinarians, primarily Drs. Jennifer Haussmann and Vickie Clyde, sedated Tula, and transported her to the Milwaukee County Zoo Animal Health Center. Following the vets and techs establishing an intravenous line, attaching a pulse-oximeter and intubation establishing general anesthesia, we were given permission to start the dental procedure.

Figure 1 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 1 photo by Mike NepperA brief oral exam revealed no other oral or dental pathology warranting treatment other than the mandibular right canine. The pulp was exposed with pulp tissue at the surface of the opening. The fractured canine segment and observation of the tooth had already established the pulp exposure (Figure 1).

The pulp was vital. The preoperative radiograph (Figure 2) revealed the pulp on this young animal widened a short distance beyond the fracture.

After explaining to the veterinarians, I used the high speed dental hand piece to cut another approximate cm off of the tooth to permit optimal pulp access for the endodontic procedure (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 2 photo by Mike Nepper Figure 3 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 3 photo by Mike Nepper Figure 4 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 4 photo by Mike NepperI extirpated the pulp and nervous tissue with a 100 mm endo file. Working length was established at 72 mm. This correlated with my measurement and estimation from the preoperative radiograph. Using successively larger diameter files, and copious irrigation with NaOCl and RC prep the canal was shaped and dissenfected (Figures 5, 6 and 7).

Figure 5 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 5 photo by Mike Nepper Figure 6 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 6 photo by Mike Nepper Figure 7 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 7 photo by Mike NepperHemostasis was established and the pulp was dried with sterile pipe cleaners. They must be actual pipe cleaners comprised of absorbent cotton. Not colorful craft items. Bag and sterilize (Figure 8).

Figure 8 photo by Mike Nepper

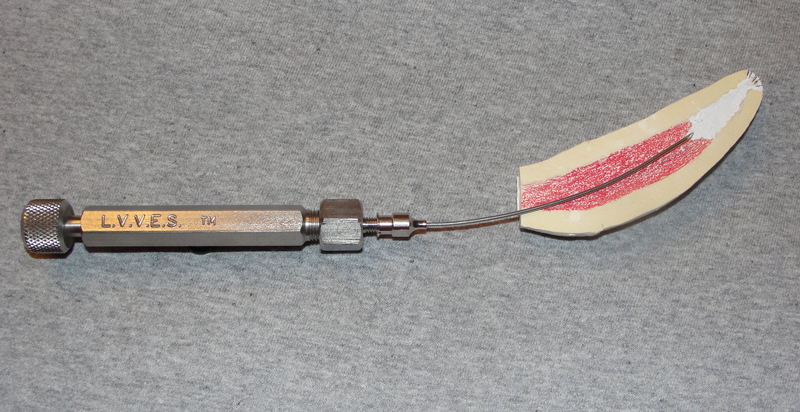

Figure 8 photo by Mike NepperAfter fitting the master gutta percha cone at the established working length, the canal was then obturated with PCA endo filler paste (a ZOE based paste) by placing the Large Volume Veterinary Endodontic Syringe needle at the apex and backfilling as it is withdrawn. The paste was deposited with a 20 gauge, 2 1/2 inch spinal needle (Figure 9). Additional gutta percha points were then placed and condensed in the canal.

A zinc phosphate cement base was placed over the endo fill. The access opening was briefly prepared and a composite resin restoration placed. I rounded and smoothed off the fractured canine edges when polishing the composite resin (Figure 10).

Figure 9 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 9 photo by Mike Nepper Figure 10 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 10 photo by Mike NepperThe entire dental procedure was completed in 53 minutes. Tula recovered from her anesthesia uneventfully. A successful procedure facillitared by excellent general anesthesia by the veterinarians. See the fill radiograph (Figure 11).

Figure 11 photo by Mike Nepper

Figure 11 photo by Mike NepperThis conventional endo approach also called coronal or orthograde is certainly the technique of choice for a fresh, vital pulp, endodontic procedure. Considering the delta apex on mature carnivore teeth, if this tooth was abscessed and or a significant amount of lysis of the apex or a large lytic area in the adjacent alveolar bone was observed, a surgical retrograde approach would have been necessary to treat properly. Also, again considering the delta apex of the tooth, periodic examination including radiography of the tooth root is necessary to monitor the success of the conventional endodontic procedure. The necessity of such follow up should be indicated in the patient's chart so that if she must be sedated for some other reason, the dental exam and radiographs will be done also.

Zookeepers are reminded to be particularly observant of behavior or signs that may indicate pain or abscessation of the tooth.

Bonobo Makanza

February, 2015Milwaukee County Zoo.Photos by Mark Scheuber, Zoo Keeper/Photographer

Maxillary left central incisor and lateral incisor residual roots. Region was inflamed, edematous prior to two weeks of antibiotic therapy.

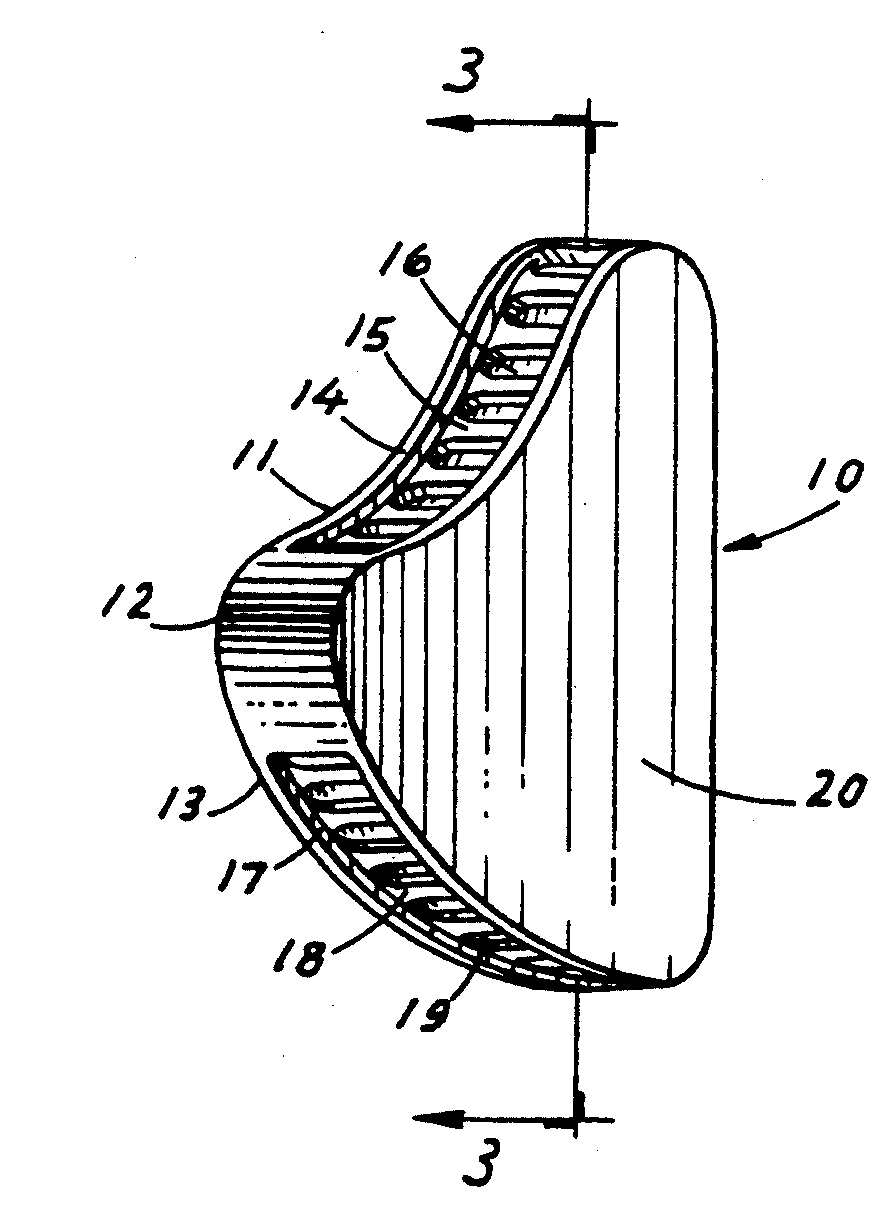

Maxillary left central incisor and lateral incisor residual roots. Region was inflamed, edematous prior to two weeks of antibiotic therapy. Conventional dental film in position. Digital Phos Phor plates were also exposed.

Conventional dental film in position. Digital Phos Phor plates were also exposed. Dr. Hausmann and Dr. Scheels positioning Nomad radiography unit.

Dr. Hausmann and Dr. Scheels positioning Nomad radiography unit. Digital image reveals periapical lesion on central incisor residual root.

Digital image reveals periapical lesion on central incisor residual root. Incision on crest of ridge.

Incision on crest of ridge. 556 surgical bur used to remove approximately 2mm. of alveolar bone surrounding each root ("ditching".)

556 surgical bur used to remove approximately 2mm. of alveolar bone surrounding each root ("ditching".) Luxator technique utilized to remove residual roots.

Luxator technique utilized to remove residual roots. Extracted roots.

Extracted roots. Roots

Roots Simple interrupted sutures placed with knots inside the wound so that Makanza will find it difficult to disturb them with his fingers and tongue.

Simple interrupted sutures placed with knots inside the wound so that Makanza will find it difficult to disturb them with his fingers and tongue.Rachel - Mongolian (Bactrian) Camel

Milwaukee County Zoo. Mongolian (Bactrian) camels

Mongolian (Bactrian) camels

Rachel with keeper Danielle

Rachel with keeper Danielle

Initial exam, Rachel sedated, flushing out food debris. Note foamy saliva, indicative of oral discomfort, constant tongue action, excessive salivation. Edema over right mandible, premolar area. Promptly identified mobile mandibular right first premolar. Removed easily. Purulent drainage flowed out of the alveolus. At that point, we realized that we had a more serious problem than just one relatively small painful tooth.

Initial exam, Rachel sedated, flushing out food debris. Note foamy saliva, indicative of oral discomfort, constant tongue action, excessive salivation. Edema over right mandible, premolar area. Promptly identified mobile mandibular right first premolar. Removed easily. Purulent drainage flowed out of the alveolus. At that point, we realized that we had a more serious problem than just one relatively small painful tooth.

Intraoral view. Note papilla on cheek. Food packed in area of pain by patient. Common sign in herbivores, attempt to relieve discomfort.

Intraoral view. Note papilla on cheek. Food packed in area of pain by patient. Common sign in herbivores, attempt to relieve discomfort.

Initial radiograph, taken after I had removed the small first premolar. Purulent exudate flowed out of alveolus. Fracture line along mesial border of second premolar. Antibiotics administered, animal allowed to recover while we discussed further treatment.

Initial radiograph, taken after I had removed the small first premolar. Purulent exudate flowed out of alveolus. Fracture line along mesial border of second premolar. Antibiotics administered, animal allowed to recover while we discussed further treatment.

Bactrian Camel Skull.

Bactrian Camel Skull.

Abscess pointed, it was explored and drain placed.

Abscess pointed, it was explored and drain placed.

Dr. Travis Henry, a board certified veterinary equine dentist, placing an equine mouth “gag” to keep mouth open for visualization and treatment.

Dr. Travis Henry, a board certified veterinary equine dentist, placing an equine mouth “gag” to keep mouth open for visualization and treatment.

Radiograph prior to extraction of premolar.

Radiograph prior to extraction of premolar.

Hallway of zoo Animal Health Center ICU/quarantine area, with equipment set up prior to procedure.

Hallway of zoo Animal Health Center ICU/quarantine area, with equipment set up prior to procedure.

Equine instruments, note Baseplate Wax. Camel skull.

Equine instruments, note Baseplate Wax. Camel skull.

Extraction forceps.

Extraction forceps.

Dr. Henry examining area, Scheels assisting, retracting.

Dr. Henry examining area, Scheels assisting, retracting.

Forceps in use.

Forceps in use.

Extracted premolar, crown segment, fractured during removal.

Extracted premolar, crown segment, fractured during removal.

Rachel in Animal Health Center Intensive Care/Quarantine stall.

Rachel in Animal Health Center Intensive Care/Quarantine stall.

Keepers assisting in sedation procedure. Two times I removed bone shards that were shed from jaw ventral border.

Keepers assisting in sedation procedure. Two times I removed bone shards that were shed from jaw ventral border.

Keepers returning Rachel to the camel area following ? months intensive care. A few days later she kicked Robert (second from left) fracturing his tibia.

Keepers returning Rachel to the camel area following ? months intensive care. A few days later she kicked Robert (second from left) fracturing his tibia.

Bird and Reptile Beaks

Bird beaks and bills, and reptile beaks are not teeth, however, often dentistry techniques have been attempted to repair them. Beaks and bills are made of keratin, not enamel and dentin. There grow in numerous configurations throughout the life of the animal, with a wide range of vascularity.

I attempted to repair various configurations with a range of success. Early on, I like many others was “learning on the job”.

Some basic facts to know are that you cannot bond composite resin restorations to keratin. The nature of the surface and its’ continuous growth will not accept bonding adhesion. Placing retentive pins does not solve that challenge. Slower growing beaks or bills may seem to accept prosthetic additions, but they will eventually fail with even seemingly solid fixation.

If vascular support remains, a damaged beak or bill can grow, so sometimes prosthetic support will allow repair or even regrowth. In these cases, again due to the constant growth, this almost always requires close monitoring and additional repair measures. One should always use the simplest, least intrusive measures, to allow the patient optimum function, with minimum interference to function.

These days there are numerous references to be found on the internet on beak and bill repairs.

- "Treatment and Stabilization of Beak Symphyseal Separation Using Interfragmentary Wiring and Provisional Bis Acryl Composite" Journal of Veterinary Dentistry 2014,Vol. 31, ppg. 255-262. Charles Lothamer DVM, Christopher J. Snyder DVM, Christoph Mans Dr. Vet Med DACZM ECZM, Jason Soukup DVM

First attempt to reattach, using bonding only to remnants of beak at germinal layer. This failed within a couple days.

First attempt to reattach, using bonding only to remnants of beak at germinal layer. This failed within a couple days.

Green conure maxillary beak reattachment. Following technique published by Dr. Thomas Clark (Louisville Zoo) used on a salmon crested cockatoo. Beak sloughed off due to an infection at the germinal base. I did attempt to bond with composite resin to the remaining beak base. However, it failed in just a few days. Procedure done with veterinarian Dr. Steven P Raabe.

Green conure maxillary beak reattachment. Following technique published by Dr. Thomas Clark (Louisville Zoo) used on a salmon crested cockatoo. Beak sloughed off due to an infection at the germinal base. I did attempt to bond with composite resin to the remaining beak base. However, it failed in just a few days. Procedure done with veterinarian Dr. Steven P Raabe.

Orthodontic wires placed through the skull.

Orthodontic wires placed through the skull.

Beak rebuilt with composite resin, bulk done prior to procedure anesthesia, in place. Wires bent to engage slots cut into the beak.

Sheet plastic was bonded inside to create a horizontal barrier, separating oral cavity and nasal openings.

Beak rebuilt with composite resin, bulk done prior to procedure anesthesia, in place. Wires bent to engage slots cut into the beak.

Sheet plastic was bonded inside to create a horizontal barrier, separating oral cavity and nasal openings.

Finished beak. Proved totally functional for years. Owners moved and we learned that they had a dentist reinforce it with resin when it was becoming loose.

Finished beak. Proved totally functional for years. Owners moved and we learned that they had a dentist reinforce it with resin when it was becoming loose.

South American Jay. Lower beak split due to trauma.

Composite bonding was attempted to splint them together. However, after it failed, a combination of orthodontic elastics and a pliable band that is commonly used to color code the handles of dental instruments was used. They proved to be effective and allowed the beak to grow and eventually repair it self.

South American Jay. Lower beak split due to trauma.

Composite bonding was attempted to splint them together. However, after it failed, a combination of orthodontic elastics and a pliable band that is commonly used to color code the handles of dental instruments was used. They proved to be effective and allowed the beak to grow and eventually repair it self.

African spoonbill. Upper beak was bent up due to trauma while being transported to our zoo. Bird unable to grasp food with the beak bent up, flexing at the fracture joint. A six inch plastic ruler was used as a rigid splint. I rounded off the corners. I wrapped flexible metal mesh, used to splint loosened teeth, around the bill, fastening the ends with composite resin. Note the red vascular supply around the circumference of the bill. This clearly provided a regeneration of the bill in the broken area. When we removed the splint in approximately six weeks, the broken area was rigid, repaired.

African spoonbill. Upper beak was bent up due to trauma while being transported to our zoo. Bird unable to grasp food with the beak bent up, flexing at the fracture joint. A six inch plastic ruler was used as a rigid splint. I rounded off the corners. I wrapped flexible metal mesh, used to splint loosened teeth, around the bill, fastening the ends with composite resin. Note the red vascular supply around the circumference of the bill. This clearly provided a regeneration of the bill in the broken area. When we removed the splint in approximately six weeks, the broken area was rigid, repaired.

Haley, Polar Bear

Brookfield ZooAbscessed mandibular canine extraction, following failed endodontic treatmentHaley arrived at Brookfield Zoo with a draining abscess of right mandibular canine, at the root apex. At previous zoo she had coronal root canal treatment. She was less than two years old. The canal was very large, the canine immature. The apex had not matured, closed when the endodontic fill was completed. The fill material, consisting primarily of paste extruded through the open open apex. If it had been supposed to be an apexification treatment, it had failed completely, leaving her with an external fistula through the ventral border of the mandible. White paste crumbles were coming through the fistula. Dr. Meehan said the the previous zoo had not provided any dental treatment records. She was on antibiotics. We considered the treatment options. We agreed that removal of the canine would allow the bone to fill in. We agreed that bone would be stronger than trying to keep the canine, reinforcing it with a post. She was being kept apart from her future mate. We agreed to keep her apart until we did a follow up in three months. We did this to protect her from any trauma to the weakened mandible. At three months a radiograph revealed that complete bone repair had been achieved and she was then allowed to be with her mate.

Radiograph of canine endo fill Note tiny vestigal premolar distal to canine crown

Radiograph of canine endo fill Note tiny vestigal premolar distal to canine crown

Canine with amalgam restoration An incision was made on crest of ridge and the vestigial premolar removed

Canine with amalgam restoration An incision was made on crest of ridge and the vestigial premolar removed

Amalgam removed with high speed hand piece

Amalgam removed with high speed hand piece

Gutta percha fill being removed

Gutta percha fill being removed

Halls’ OS straight handpiece with round bur used to cut three longitudinal slots in the tooth

Halls’ OS straight handpiece with round bur used to cut three longitudinal slots in the tooth

Cutting slots in the tooth as far as the handpiece bur could reach

Cutting slots in the tooth as far as the handpiece bur could reach

Exudate flushing from the apex area

Exudate flushing from the apex area

Elevator use

Elevator use

Third slot being cut

Third slot being cut

The fragments, still connected near apex being loosened

The fragments, still connected near apex being loosened

The two inch plus root removed in one piece with luxators “A pink dental wax plug was formed, about half of the length of the tooth root and forced into the alveolus. Dissolving sutures were used to close as possible and hold the wax in place.”

The two inch plus root removed in one piece with luxators “A pink dental wax plug was formed, about half of the length of the tooth root and forced into the alveolus. Dissolving sutures were used to close as possible and hold the wax in place.”

Alveolus packed half depth with pink dental wax. Dissolving sutures over to close as possible and keep wax in place. It eventually dissolved and alveolus filled with bone.

Alveolus packed half depth with pink dental wax. Dissolving sutures over to close as possible and keep wax in place. It eventually dissolved and alveolus filled with bone.

Haley

Haley