Page 2 - Herbivores

Cases

Please note that as a dental consultant I will only address the dental and oral pathosis components of these cases, leaving the anesthesia and other medical treatments to the veterinarians. I will use example cases with common pathoses encountered and those which I have sufficient photo series to illustrate them.

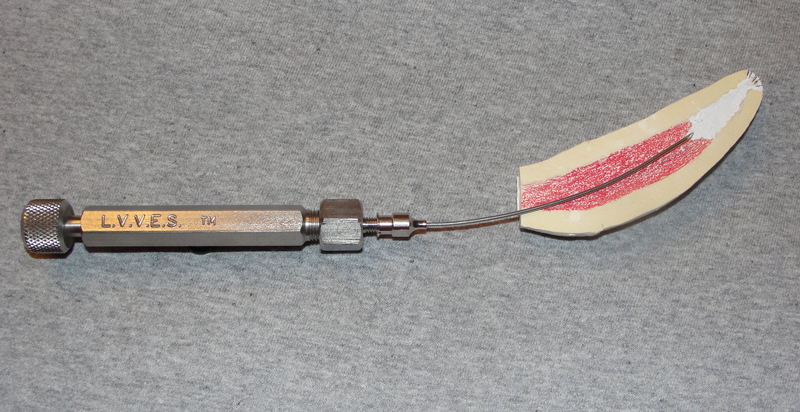

Dall Sheep Endodontic Case

When a mandibular swelling was observed on this Dall sheep ewe by an observant keeper, an anesthesia was scheduled. Under general anesthesia, radiographs revealed periapical lesions and typical bony swelling due to pulpal degeneration, infection and inflammation of the alveolar bone. The intraoral pulp exposure was due to a cusp fracture. After shaving and cleansing the region, the lesion area was entered with a lateroventral approach. After reflecting the overlying skin, the cancellous bone was curetted and cut away with surgical dental burs, always using copious amounts of coolant water. When the tooth apices were exposed a retrograde endodontic procedure was performed. It was restored with amalgam. More recently of course we have utilized EBA and MTA. The cusp fracture was restored. The surgical site was closed after contouring rough bone edges. Oral antibiotics are not an option with ruminants so catching up or squeeze caging it was required to administer injections of antibiotics for several days. Follow up examinations including radiographs revealed healing and bone fill of the mandibular ventral border.

Dall sheep: Bony lesion on jaw due to abscessed molar

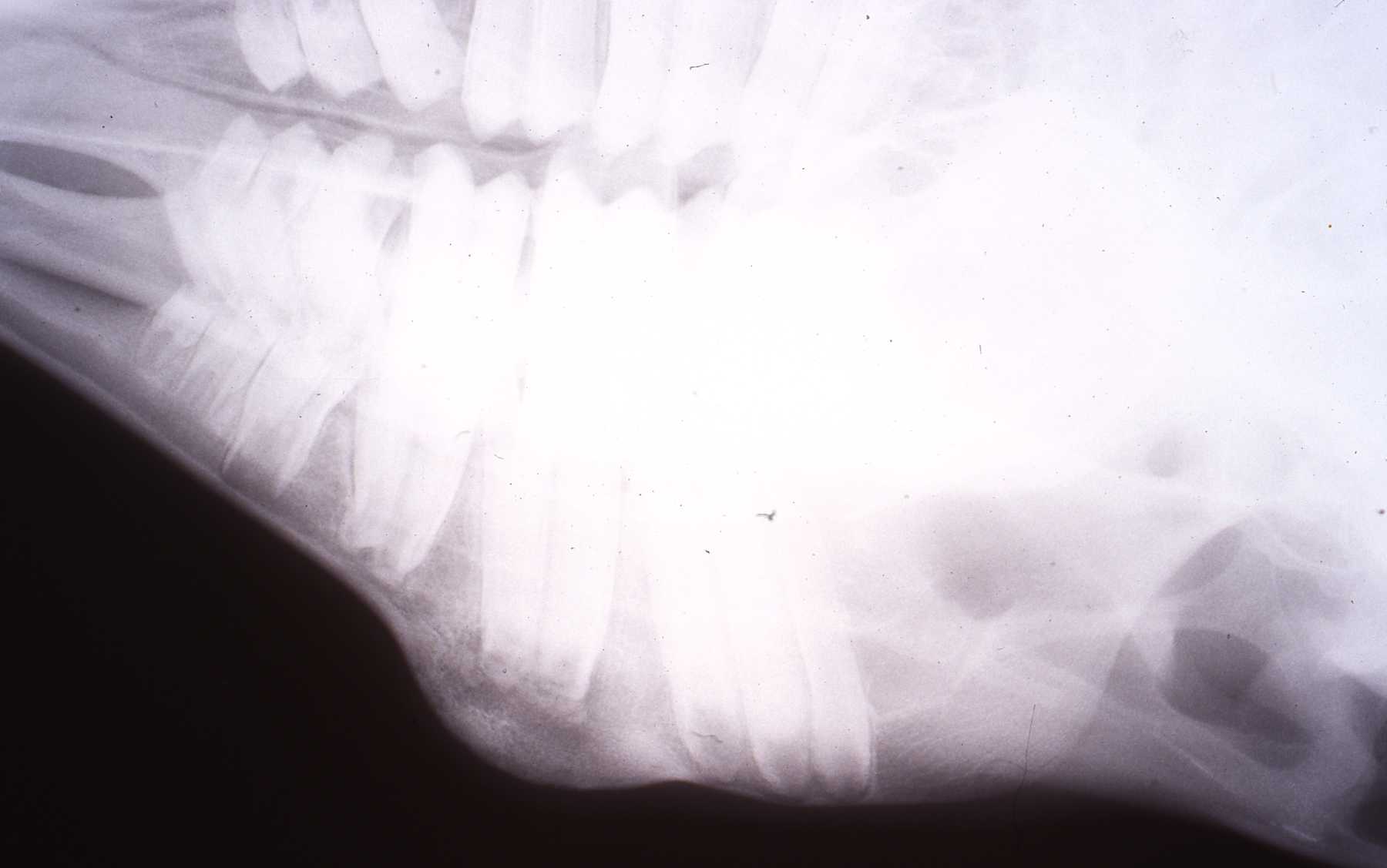

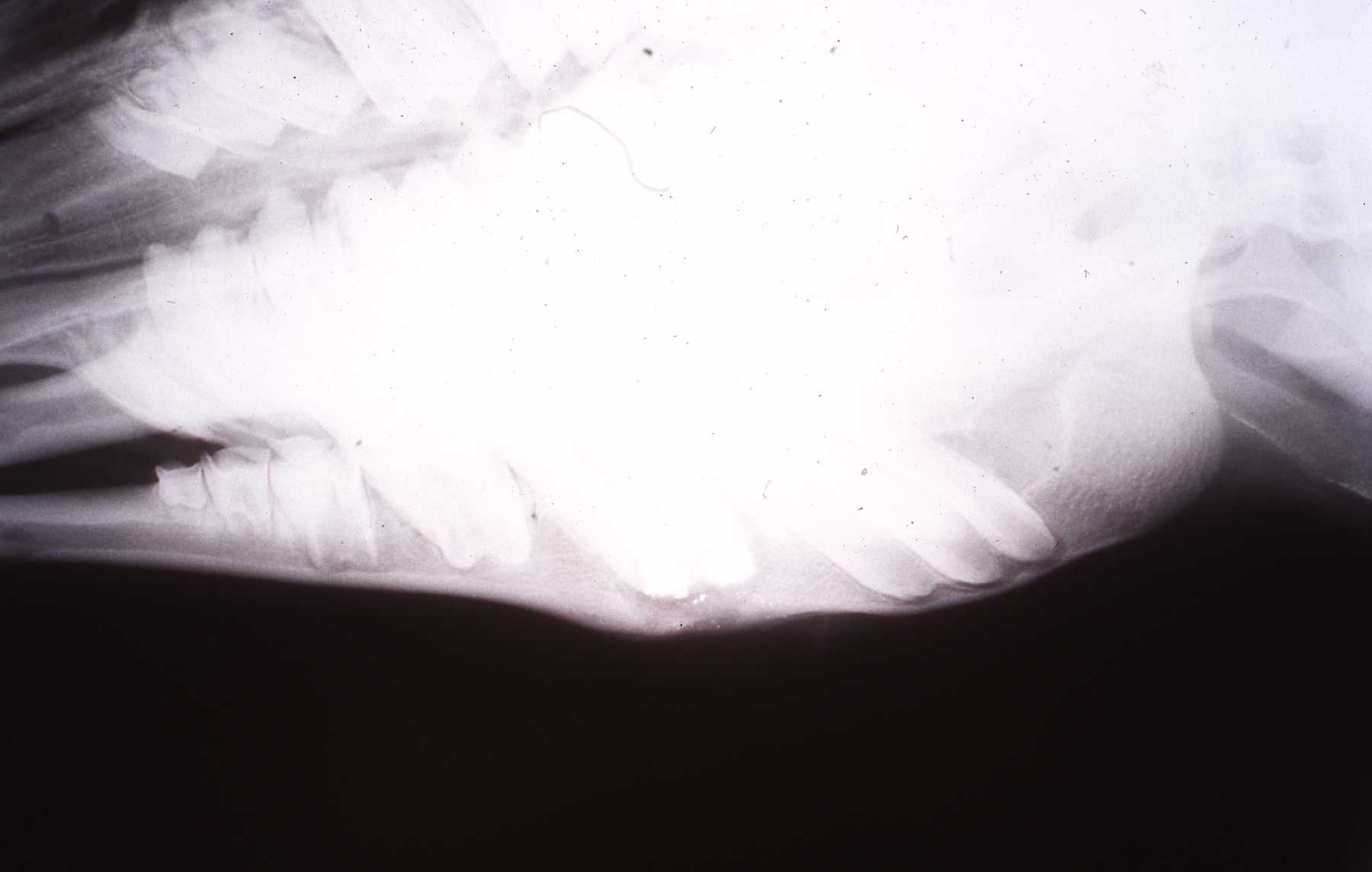

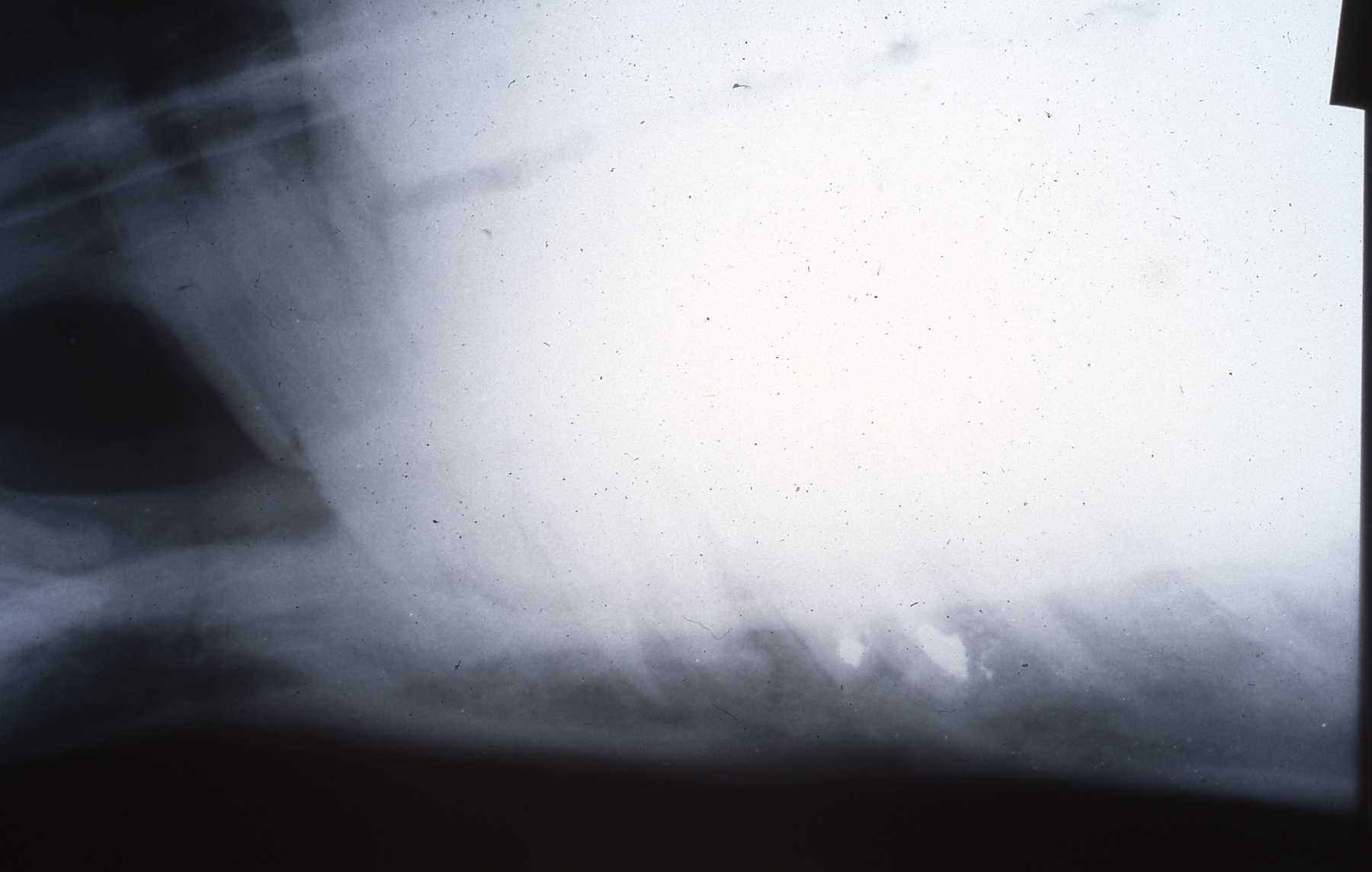

Dall sheep: Bony lesion on jaw due to abscessed molar Dall sheep: Radiograph of periapical lesion and bony swelling reaction to abscessed molar

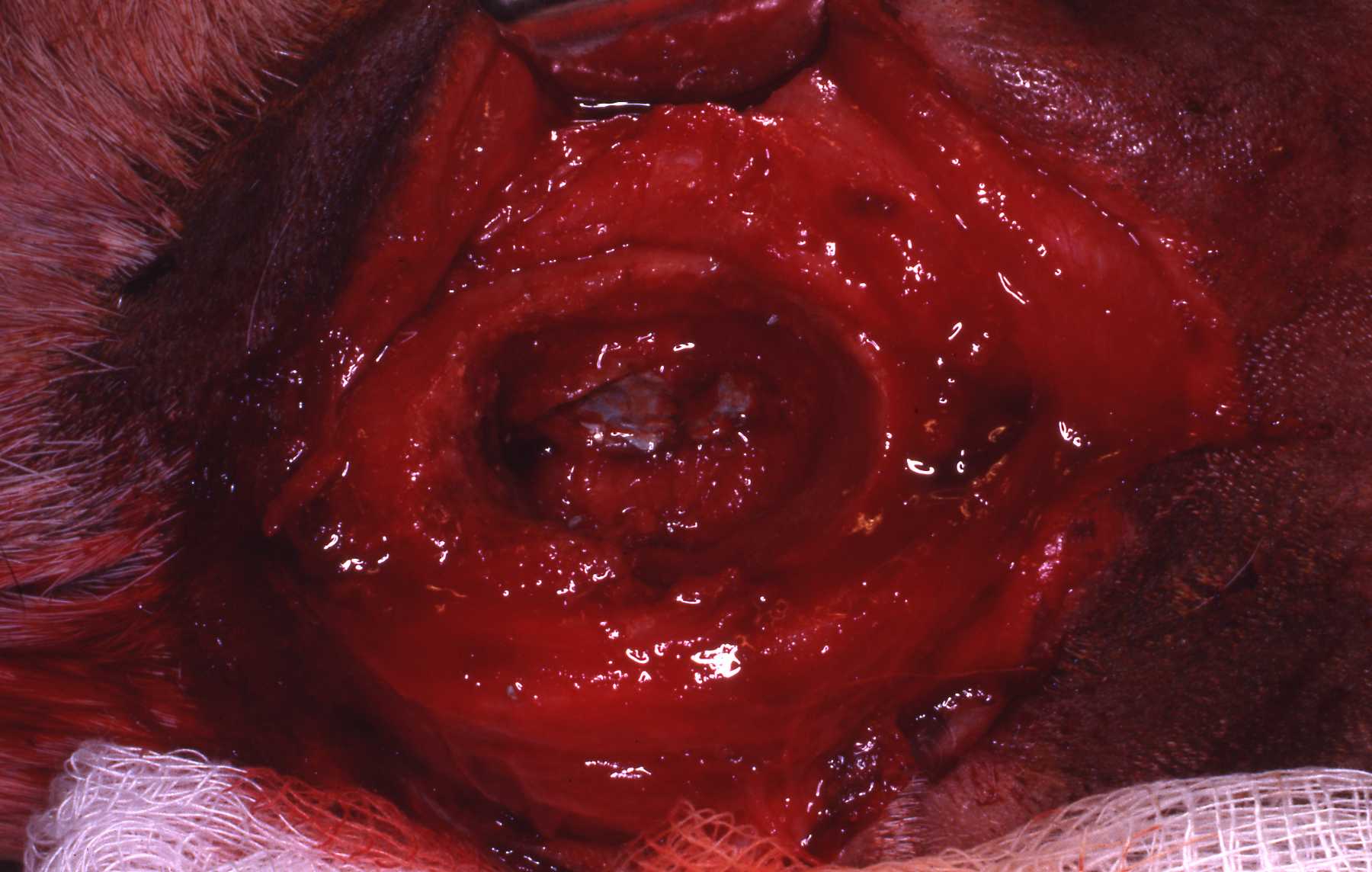

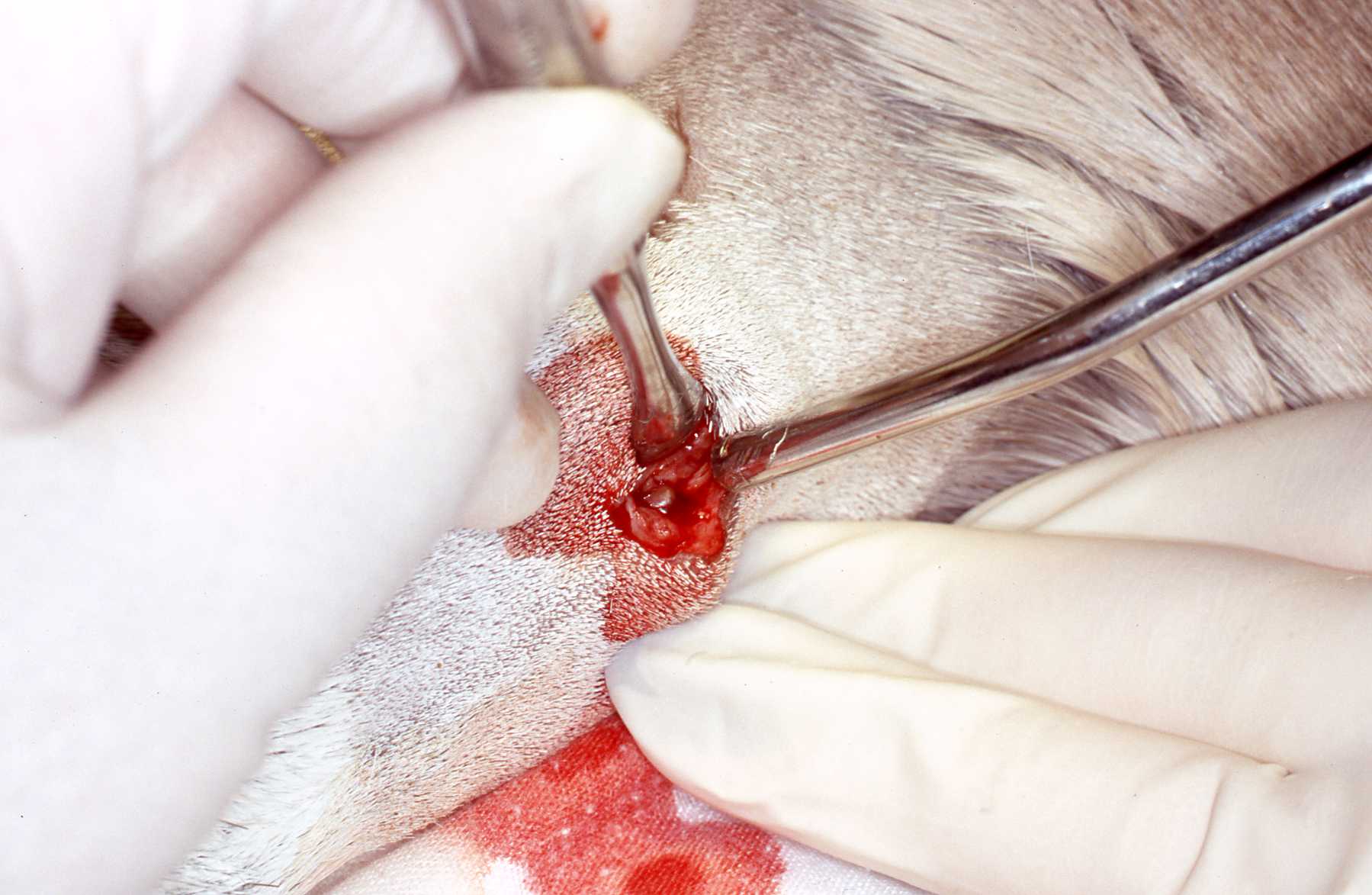

Dall sheep: Radiograph of periapical lesion and bony swelling reaction to abscessed molar Dall sheep: Surgical approach to root apices

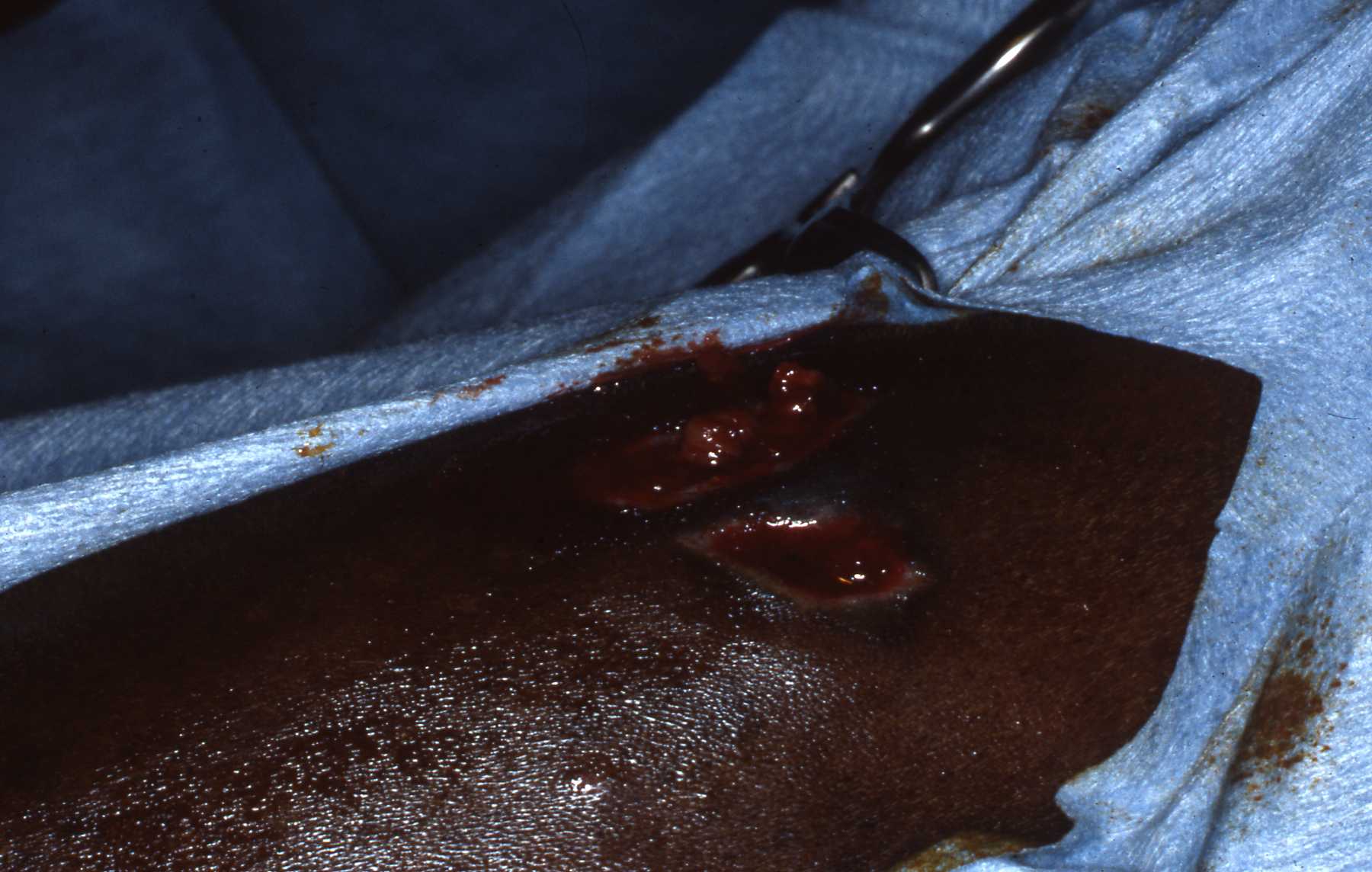

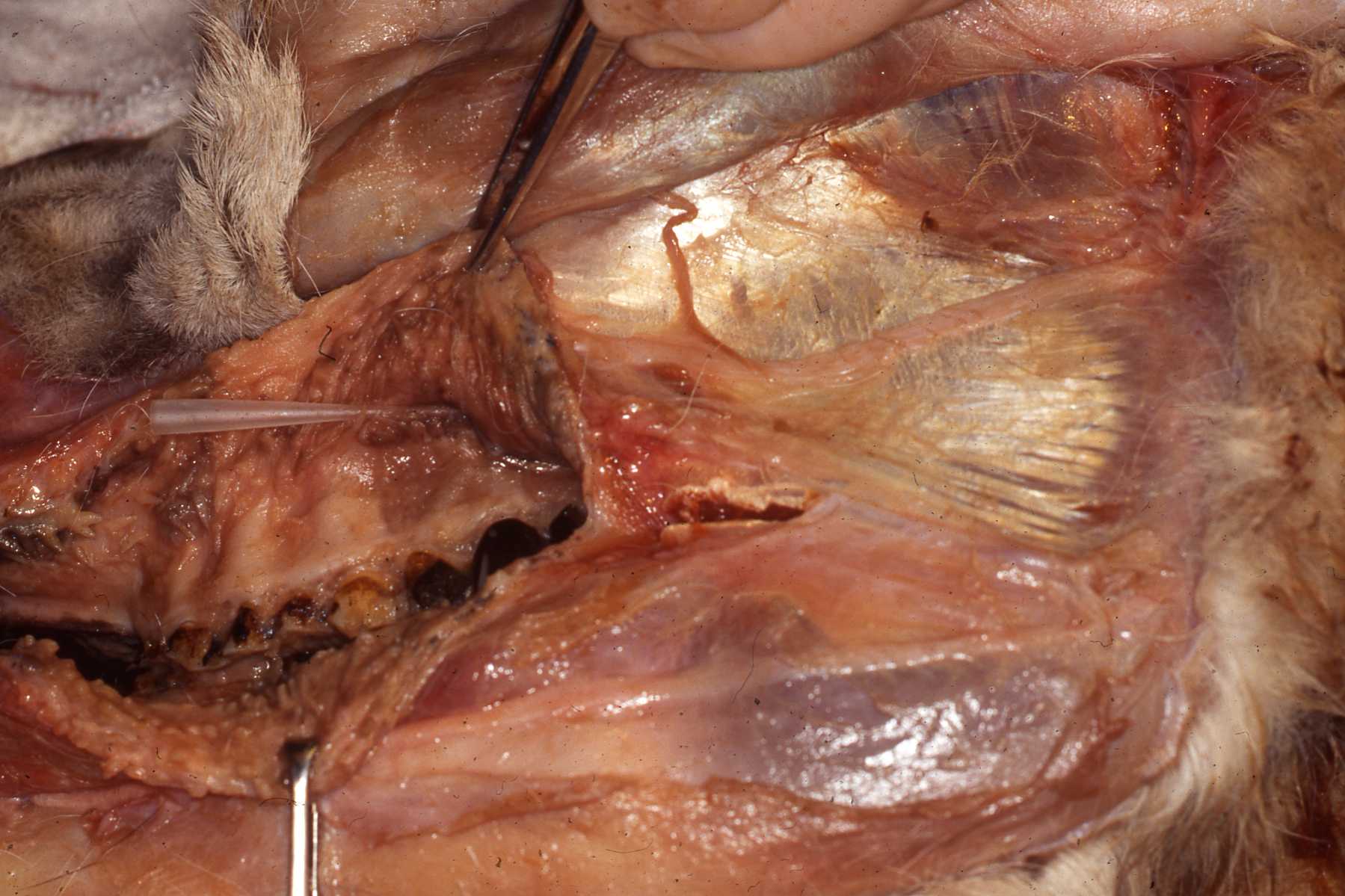

Dall sheep: Surgical approach to root apices Dall sheep: Apisectomy, retrograde fills, immediately post op

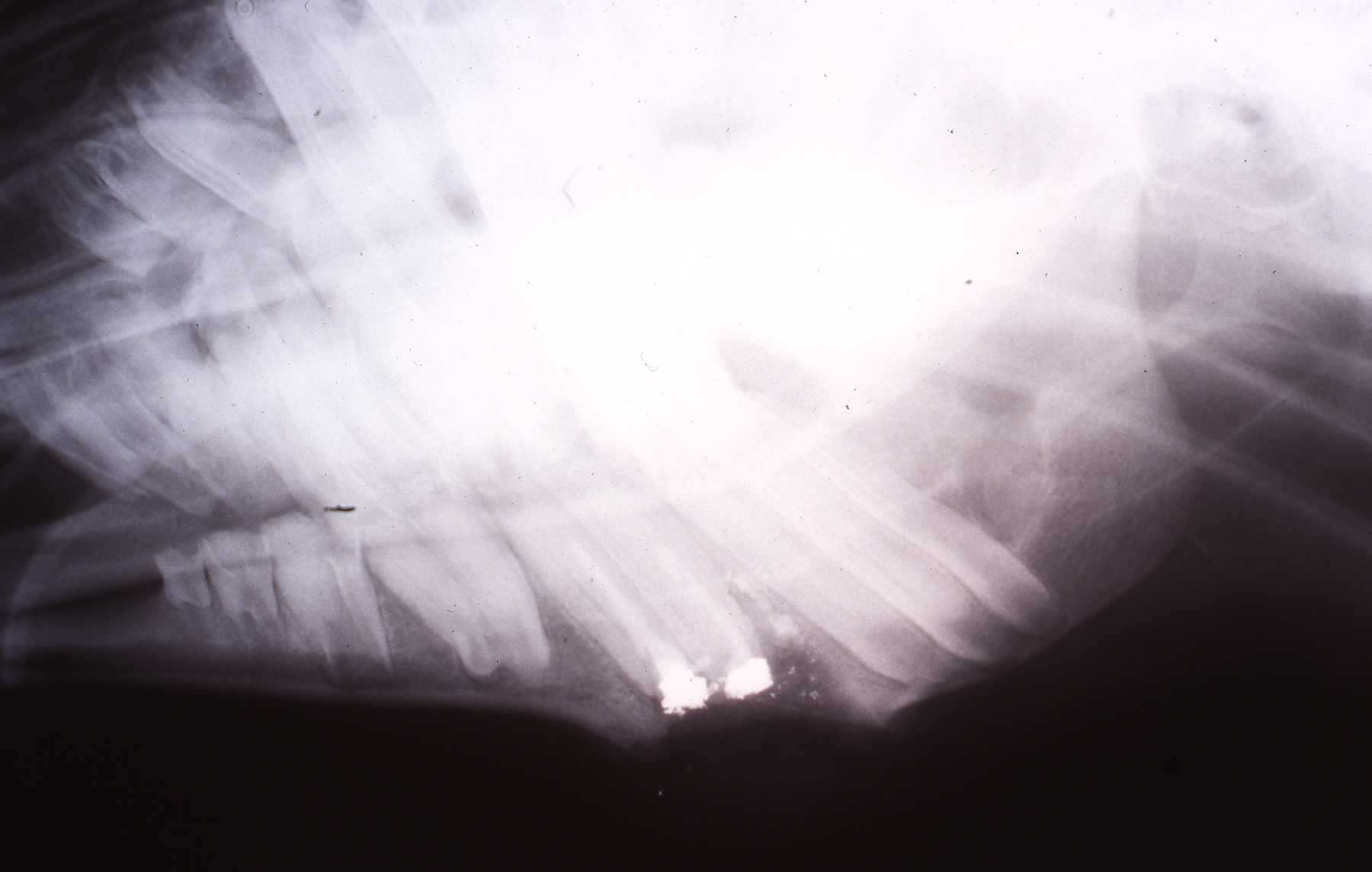

Dall sheep: Apisectomy, retrograde fills, immediately post op Dall sheep: Bone healed, 9 month follow up

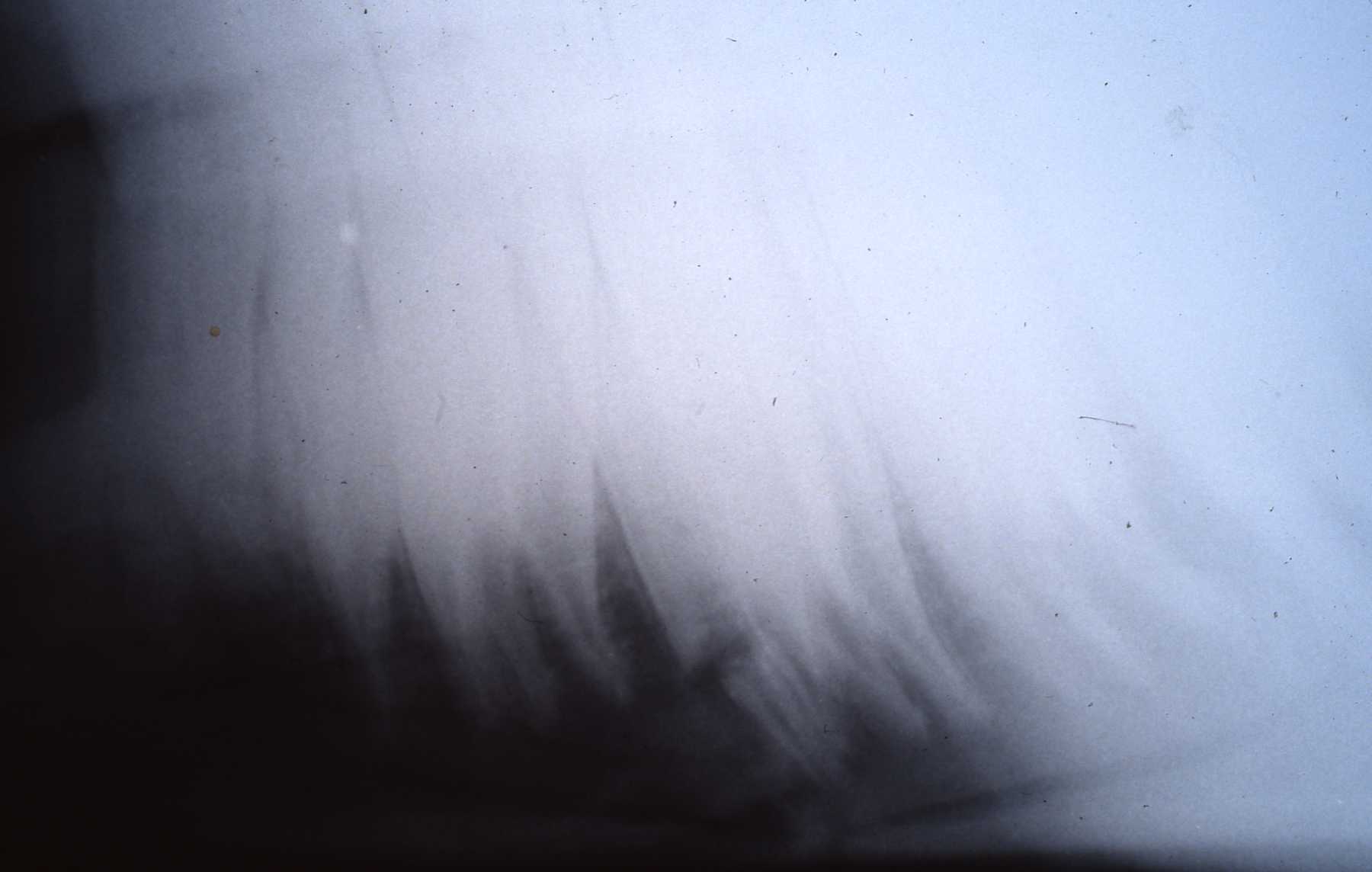

Dall sheep: Bone healed, 9 month follow upEquine Endodontic Case

When mandibular swelling was noted associated with likely a kick wound, radiographs revealed that two tooth root tips were fractured. There was no intraoral trauma or pathosis. A retrograde endodontic procedure was performed. Follow up examination and radiographs revealed good healing. And even more importantly we confirmed that the tooth continued to erupt at the same rate of the adjacent teeth. This was very satisfying to observe, because when this case was performed in the early 1990s we were not aware of anyone else doing so and recording the continued eruption. I presented this case among others at the 1994 AVDS meeting, at the exotic animal section. Again, we were using amalgam then, but utilize EBA or MTA now.

Equine: Area prepped for surgical approach

Equine: Area prepped for surgical approach Equine: Radiograph reveals roots fractured by kick to mandible

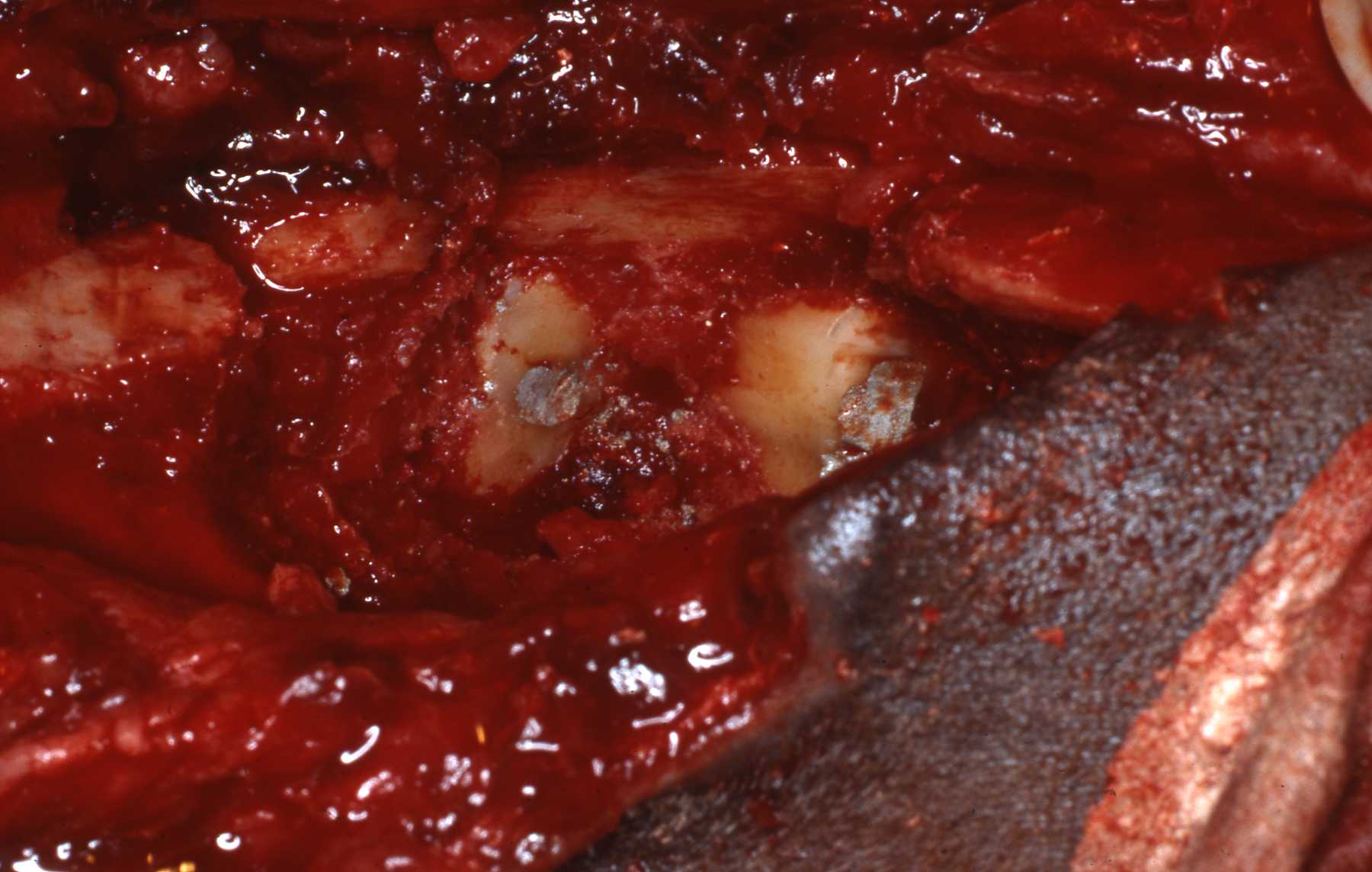

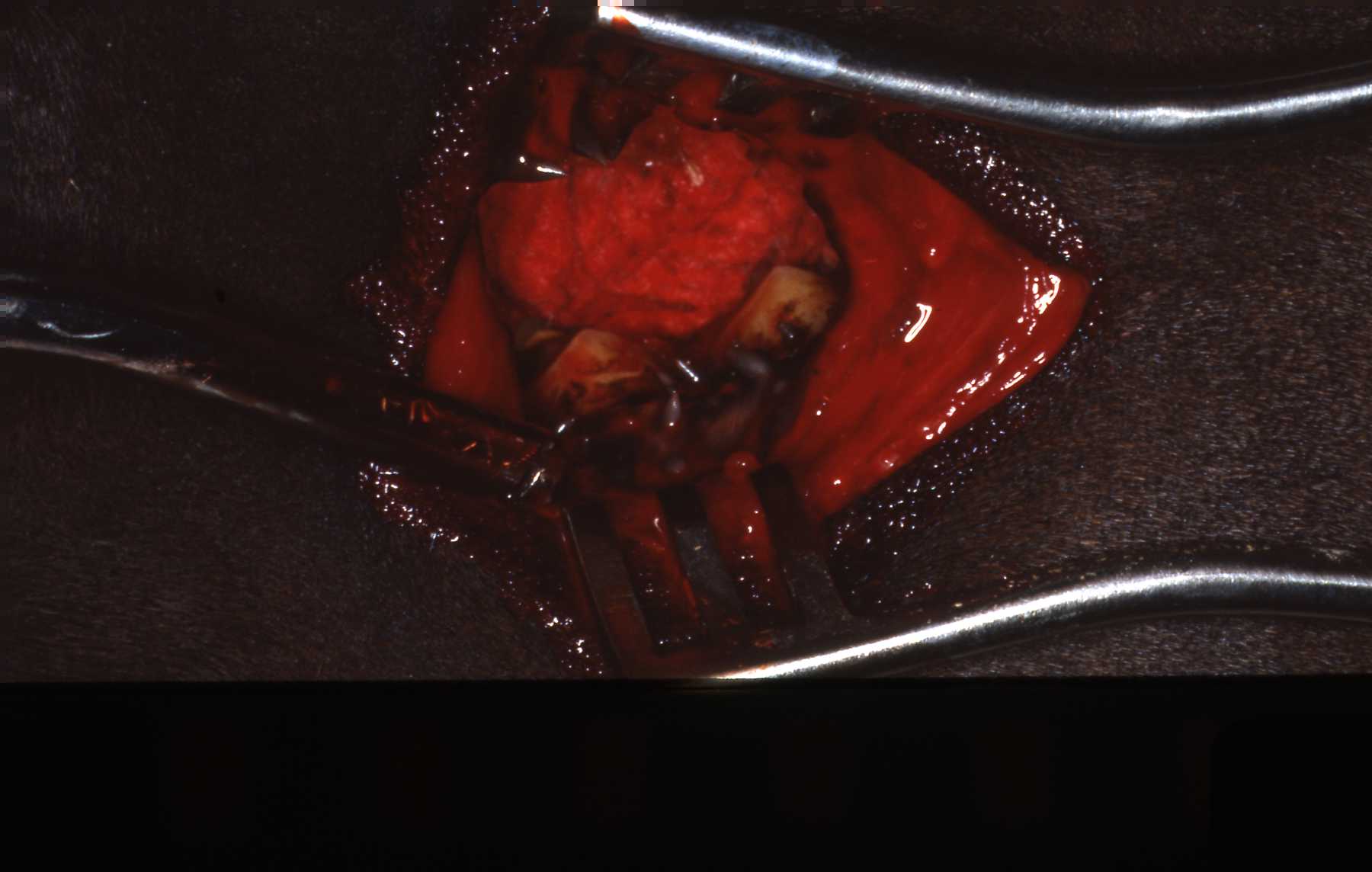

Equine: Radiograph reveals roots fractured by kick to mandible Equine: Root apisectomy, retrograde endo fills sealed with amalgam

Equine: Root apisectomy, retrograde endo fills sealed with amalgam Surgical closure.

Surgical closure. Equine: Endo fills, bone healed

Equine: Endo fills, bone healed Equine: Surgical area healed, 6 month follow up

Equine: Surgical area healed, 6 month follow upLlama and Equine Case Lessons

Among the initial large herbivore cases that I encountered, several were llamas with an abscessed mandibular premolar or molar. They presented with swellings of the bone surrounding the affected tooth abscess.

In Dr. Murray Fowlers' book on South American Camelids, which I highly recommend as a quality reference, regarding dentition and pathosis, he mentions but does not illustrate the lateral buccomoty approach to access the molar region. My friend and colleague, Dr. Peter Kertesz, recommended I practice the lateral buccotomy approach on cadavers prior to an actual case.

Working with equine veterinarian Dr. Jo Randolph, we utilized cadaver heads to review the anatomy of llama and equine oral cavities prior to using the lateral buccotomy approach. With thorough preparation I have successfully used the lateral buccotomy approach on llamas, horses and other species with similar anatomy.

Llama: Cadaver dissection, note probe in Stensons' duct

Llama: Cadaver dissection, note probe in Stensons' duct Llama: Lateral buccotomy, horizontal incision, approach to extract molar

Llama: Lateral buccotomy, horizontal incision, approach to extract molar Llama: Healing surgical area.

Llama: Healing surgical area.If an abscessed posterior tooth is beyond repair, it usually should be extracted. I say "usually" because in some species, considering the patients' entire dentition, removing an abscessed tooth may be worse than keeping it in position. For example, in some species such as rhinos and tapirs extraction may be all but impossible. Even if it was done, and theoretically it could be, the risks of jaw fracture, and limitations of follow up care due to anesthesia considerations are riskier than treating a low grade chronic infection.

A common llama case presentation is an abscessed third premolar or first molar. Swelling on the mandible is usually the first sign noticed by caregivers. By this stage in the pathosis, usually a significant periapical lesion has developed including lysis of the root apices. The usual treatment considered on these easily managed animals is extraction. However, a retrograde endodontic approach should certainly be considered to maintain the tooth. This has been described.

Extraction through the oral cavity in these species is very challenging. Again, currently equine veterinary dentists are using the oral approach in horses and llamas regularly these days with improved equipment and training. I can attest that these are very challenging because of experience. Note that the roots of the llama mandibular molars are very wide and can be convoluted.

The etiology of the abscess is usually due to enamel fractures leading to pulp exposure, or advanced periodontal disease associated with malocclusion. If endo is to be considered, one must consider whether the original etiology can be resolved also.

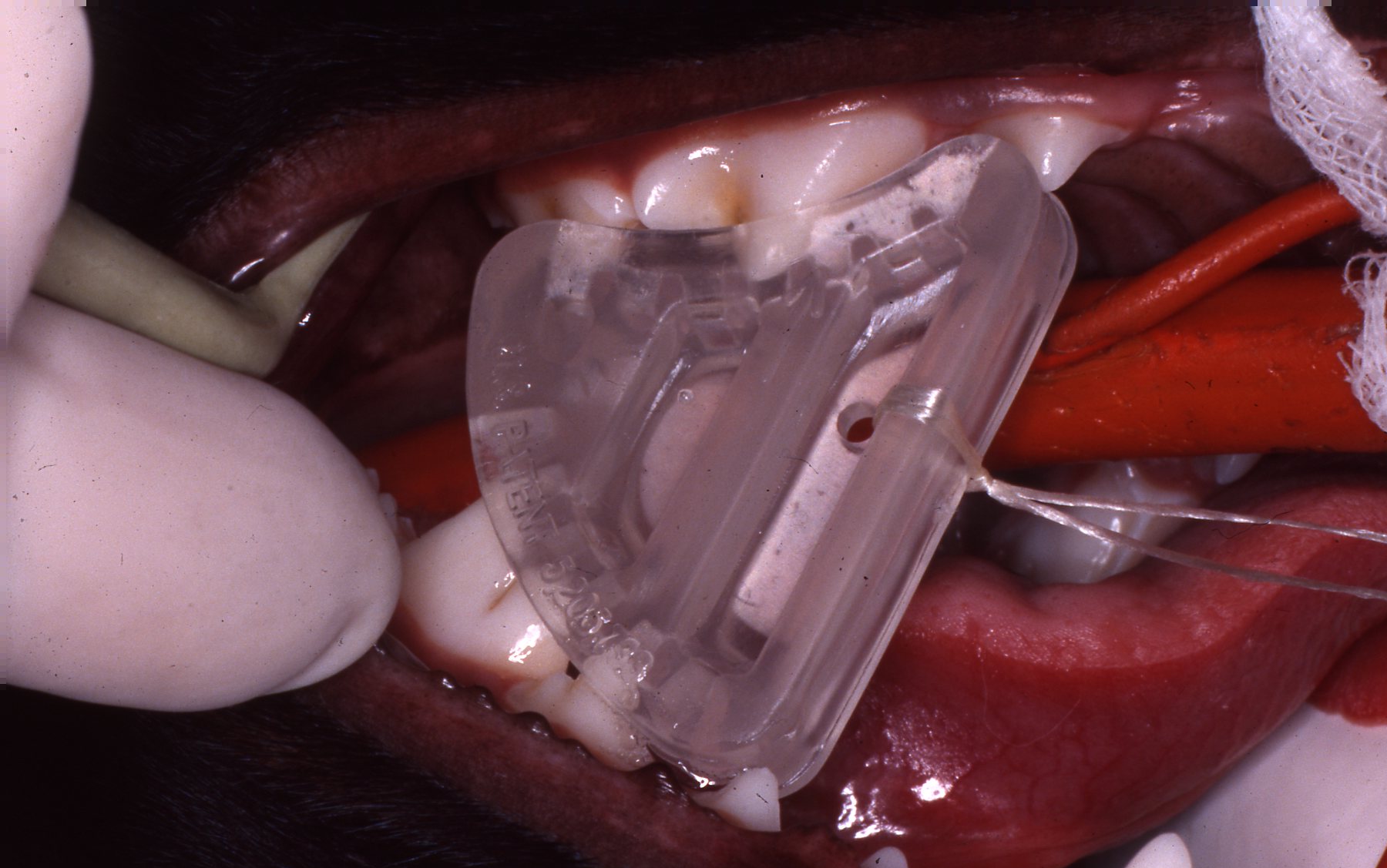

To access the posterior teeth using the lateral buccotomy, follow proper surgical protocol cleansing the oral cavity and surgical site. The lateral buccotomy incision is made at the level of the occlusal plane in the horizontal plane. Visualize the orifice of Stensons duct from the parotid gland, to avoid severing the duct. Consider inserting a flexible piece of plastic to monitor its position. Dissect carefully to avoid any significant vascular vessels or branches of the facial nerve. Avoid cutting the masseter muscle if possible, but for more posterior teeth it may need to be dissected. The skin, buccinator muscle and oral mucosa will be encountered. Utilizing retractors the tooth can now be accessed. The tooth can be sectioned and an appropriately designed gingival flap made to access and remove buccal bone overlying the roots. A key point is to design the flap so that suturing is done over solid bone to avoid flap dehiscence. Following appropriate alveoplasty and flap closure the cheek can be closed in layers.

Another key element of managing an extraction, especially on a mandibular tooth on a patient whose diet cannot be altered and that will not be readily sedated or anesthetized for follow up care is how to manage the extraction site. The question is whether to close the extraction site, the alveolus and if you cannot, which is usually the case, how to keep food from entering the alveolus. First, it is difficult if not impossible to surgically close a mandibular extraction site in any species with the ideal tensionless flap, without creating additional surgical wound issues. It is much easier on maxillary sites, but with gravity in its favor, maxillary surgical sites do not present the same magnitude of food impaction issue.

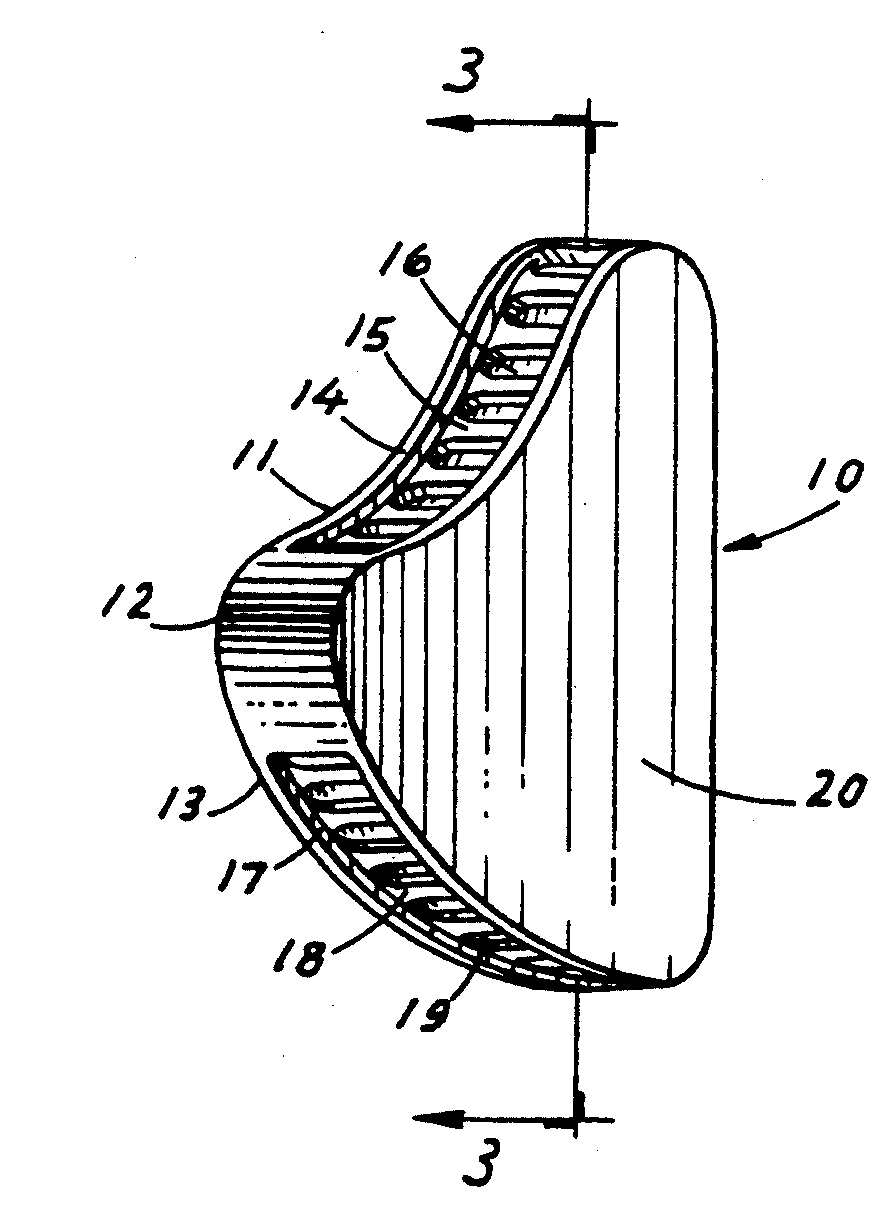

In the late 1980s or early 1990s I came upon the idea of using dental waxes to close plug the alveoli. I was aware of the various techniques used at the time, some quite ancient and crude to plug and manage dental surgical sites. I know that many other people, especially in the equine field came upon the wax technique also. We discovered this among us at various veterinary dental meetings. I have used the wax plug technique successfully in mandibular extraction cases in many species, ranging from moose to warthogs.

When hemostasis is achieved the plug is formed from pink sheet dental wax to fit the alveolus very tightly. It should be approximately one half of the length of the extracted tooth root. This allows granulation in the base of the alveolus. When the wax plug is eventually lost primary healing will have occurred, the effect of food impaction and eventual infection is minimized. *See the tooth extraction section of this site for pictures of wax plug use.

Spekes Gazelle Case

Spekes gazelle presenting with swelling on left mandible. Bony enlargement is reaction to dental infection. History of dental pathosis in primary dentition at previous institution.

Spekes gazelle presenting with swelling on left mandible. Bony enlargement is reaction to dental infection. History of dental pathosis in primary dentition at previous institution. Draining lesion on ventral border of mandible over enlarged bony region.

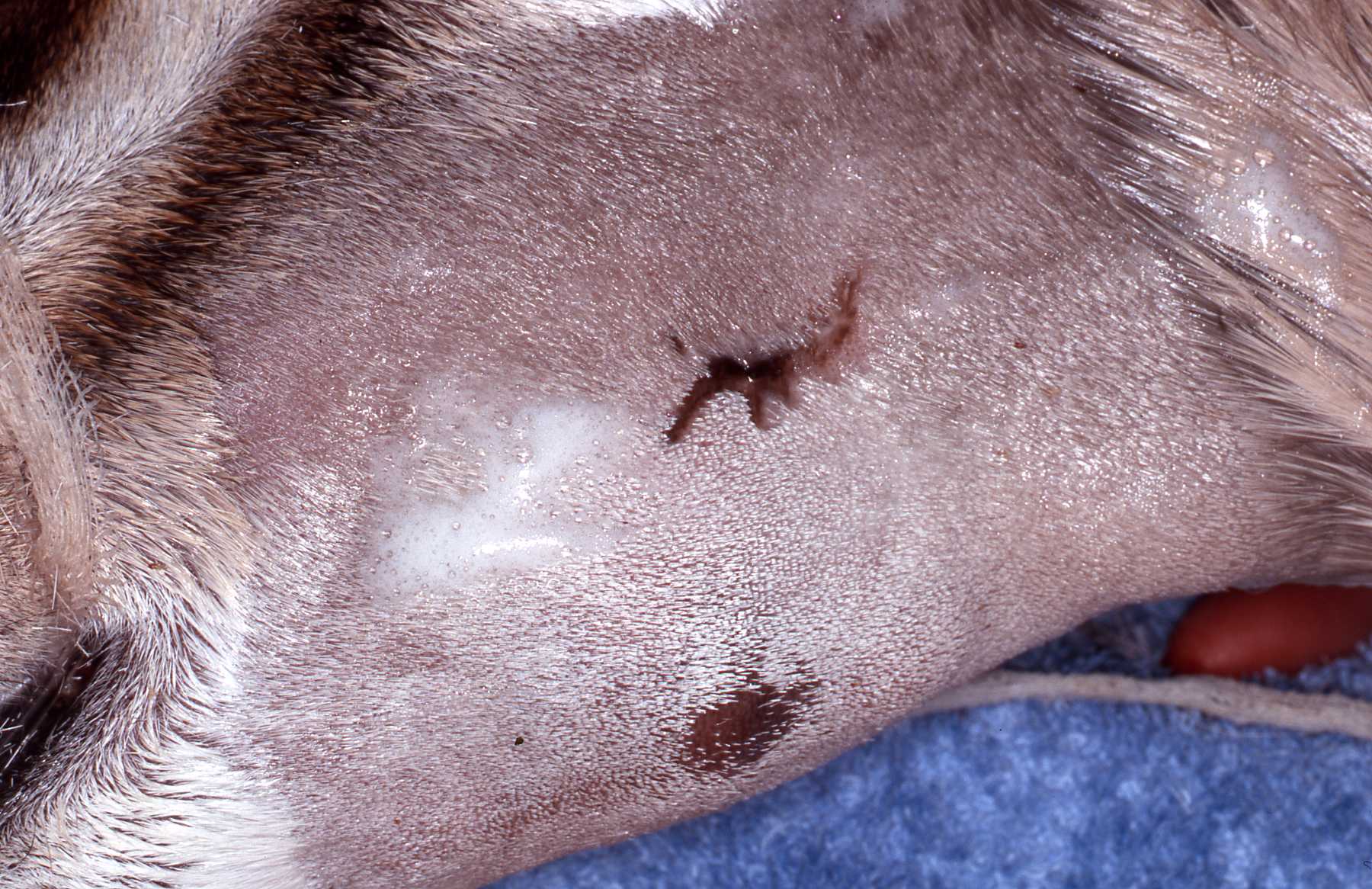

Draining lesion on ventral border of mandible over enlarged bony region. Shaving of hair reveals bony enlargement and two draining tracts.

Shaving of hair reveals bony enlargement and two draining tracts. Lesions over enlarged bony area.

Lesions over enlarged bony area. Intraoral exam revealed malformed, vertically fractured third mandibular premolar.

Intraoral exam revealed malformed, vertically fractured third mandibular premolar. Extracted fractured tooth fragments, granulomatous tissue and impacted food particles.

Extracted fractured tooth fragments, granulomatous tissue and impacted food particles. Initial surgical approach in drainage tract area revealing layers of honeycomb like secondary bone growth resulting from the chronic infection in mandible.

Initial surgical approach in drainage tract area revealing layers of honeycomb like secondary bone growth resulting from the chronic infection in mandible. Following thorough removal of secondary bone layers, debridement and irrigation, beads impregnated with antibiotics are placed into surgical site which is closed with drain sutured in place.Note: When possible a culture is taken of the wound area prior to the procedure date to determine which antibiotics should be chosen for the surgical site treatment. This case healed well with no additional bony enlargement.

Following thorough removal of secondary bone layers, debridement and irrigation, beads impregnated with antibiotics are placed into surgical site which is closed with drain sutured in place.Note: When possible a culture is taken of the wound area prior to the procedure date to determine which antibiotics should be chosen for the surgical site treatment. This case healed well with no additional bony enlargement.This page:

Cases

Page 1: Discussion